Narrative Affect and the End of Public Opinion

book review

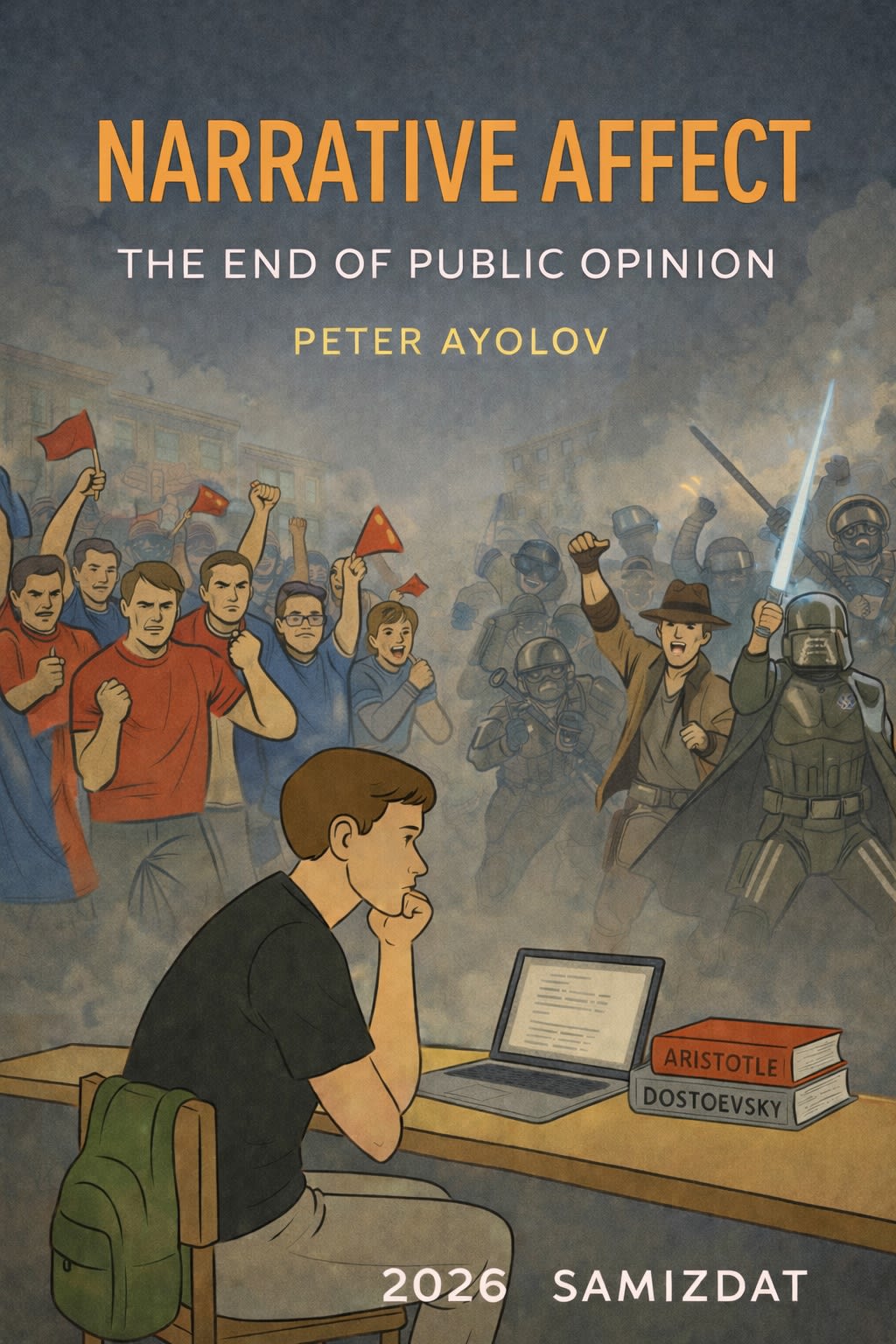

In Narrative Affect: The End of Public Opinion, Peter Ayolov advances a forceful and timely argument: that contemporary mass media no longer operates primarily through persuasion, belief formation, or the shaping of public opinion, but through the orchestration of affective environments that precede and structure thought itself. The book proposes not merely a revision of existing media theory, but a conceptual displacement of one of its foundational assumptions—that influence flows through opinion. What governs contemporary public life, Ayolov argues, is not what people think, but what they are made to feel before thinking begins.

The book is explicitly positioned as a continuation of The Media Scenario: Scriptwriting for Journalists (2026), and the two works are best read together. Where the earlier volume analysed how media increasingly constructs reality as scripted scenarios—inviting audiences into roles, anticipations, and participatory frames—Narrative Affect explains why such scenarios succeed. Their effectiveness does not rest on credibility or argument, but on affective capture. Media scenarios hold because they resonate emotionally, align with bodily intensities, and stabilise participation through shared moods rather than shared beliefs. One book maps the architecture of media experience; the other explains its emotional physics.

At the core of Ayolov’s intervention is a decisive distinction between narrative effect and narrative affect. Narrative effect names a familiar cognitive operation: the retrospective imposition of coherence on events, the construction of meaning through explanation, causality, and interpretation. Narrative affect, by contrast, operates pre-cognitively. It refers to the bodily, emotional, and atmospheric forces through which stories grip attention, synchronise feeling, and orient behaviour in advance of judgement. Contemporary media power, Ayolov shows, functions primarily at this affective level. Stories no longer persuade by argument; they invite inhabitation. They do not ask audiences to agree; they ask them to feel themselves inside a world.

This shift, the book argues, explains a series of otherwise puzzling features of contemporary public life: the failure of factual correction, the persistence of polarisation despite shared information, the resilience of symbolic worlds against disconfirmation, and the declining relevance of polling and opinion measurement. Public opinion presupposes distance, deliberation, and judgement. Narrative affect collapses these distinctions by operating directly on attention, emotion, and identity. Under these conditions, disagreement is no longer experienced as a difference of view, but as a threat to the affective coherence of one’s lived narrative environment.

Drawing on affect theory, media studies, political communication, and cultural analysis, Ayolov develops Narrative Affect Theory as a framework for understanding this transformation. Affect is treated not as a secondary emotional response to information, but as a precondition of social reality. Mood, intensity, and atmosphere shape what becomes thinkable, sayable, and believable. Media power therefore operates first at the level of feeling—through fear, urgency, belonging, outrage, or anticipation—and only later crystallises into stories, judgements, and opinions. In this sense, affect is not a reaction to events; it is what makes events socially real in the first place.

One of the book’s strengths lies in its redefinition of familiar media phenomena. Selective exposure, for example, is reframed not as a cognitive bias or informational deficit, but as an affective survival strategy. Individuals curate media environments less to confirm beliefs than to preserve emotional coherence, identity continuity, and narrative stability. What appears as avoidance of opposing views is, at a deeper level, avoidance of affective disruption. Similarly, political polarisation is analysed not as a divergence of opinions, but as the separation of affective worlds—distinct emotional grammars and narrative rhythms that render dialogue impossible because shared affective ground has dissolved.

Ayolov’s analysis also carries significant implications for understanding power. Persuasion, ideology, and propaganda no longer function primarily through explicit messaging or doctrinal repetition. Instead, power operates through pre-narrative affective modulation—the shaping of emotional atmospheres before conscious interpretation begins. Narratives then function as secondary captures of affect, providing retroactive explanations for feelings that have already oriented action. In this model, influence does not require conviction. Participation is stabilised by resonance, not belief.

The book’s conclusion sharpens these insights into a broader historical diagnosis. The end of public opinion is not the end of influence, but the beginning of its affective form. Twentieth-century mass communication sought to shape what people think; contemporary media governs how situations feel, how quickly reactions occur, and which emotional responses appear natural or unavoidable. Public life has become a competition between narrative universes rather than a debate between opinions. Cohesion is produced not by agreement, but by shared affective immersion.

Crucially, Narrative Affect does not abandon the question of truth. Instead, it relocates it. Truth is no longer defeated primarily by misinformation or error, but by affective architectures that make truth unbearable, irrelevant, or emotionally uninhabitable. Under conditions of affective governance, the problem is not that people are misinformed, but that correction fails to register because it does not align with the emotional conditions that structure reality. Journalism, therefore, is no longer only a practice of reporting or framing events, but a form of affective design with ethical consequences.

As a work of theory, the book is ambitious, synthetic, and deliberately unsettling. It challenges inherited assumptions in media studies, political communication, and democratic theory, while offering a vocabulary capable of describing contemporary media power without nostalgia for a rational public sphere that may never have existed in the form imagined. Its significance lies not in offering solutions or prescriptions, but in clarifying the terrain on which questions of truth, responsibility, and resistance must now be posed.

Narrative Affect: The End of Public Opinion is best read not as a commentary on media pathologies, but as a diagnosis of a structural transformation in how collective life is organised. It provides scholars, journalists, and critical readers with a framework for understanding why persuasion no longer persuades, why debate no longer stabilises consensus, and why power increasingly resides in the management of feeling rather than belief. In doing so, it marks an important contribution to contemporary media theory—and a sober reminder that the struggle over public life has moved beneath the level of opinion, into the deeper terrain of affect.

About the Creator

Peter Ayolov

Peter Ayolov’s key contribution to media theory is the development of the "Propaganda 2.0" or the "manufacture of dissent" model, which he details in his 2024 book, The Economic Policy of Online Media: Manufacture of Dissent.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.