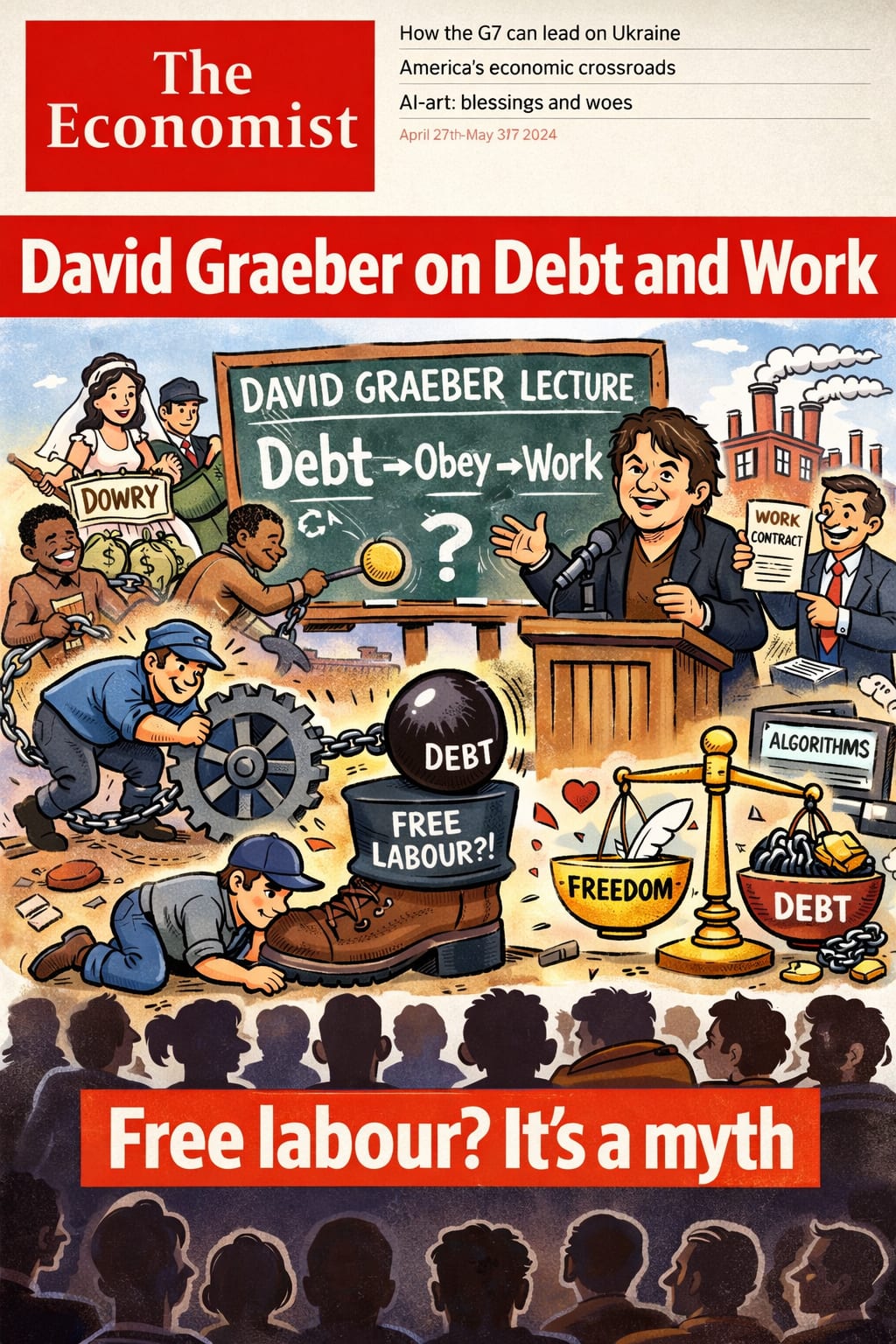

Working for Debt

David Graeber on Why ‘Free Labour’ Is a Myth

Working for Debt: David Graeber on Why ‘Free Labour’ Is a Myth

(review of David Graeber’s 2018 lecture Debt, Service, and the Origins of Capitalism)

Peter Ayolov, Sofia University "St. Kliment Ohridski", 2026

Abstract

This review examines David Graeber’s 2018 lecture David Graeber on Debt, Service, and the Origins of Capitalism, delivered at the University of Birmingham and published on YouTube, from the vantage point of 2026. The lecture is read as a condensed synthesis of Graeber’s wider intellectual project, linking his anthropology of debt to a long historical genealogy of labour, marriage, service, and wage relations. Rather than treating debt as a technical economic instrument, Graeber presents it as a moral force capable of transforming social relations into commodities and rendering relations of dependency acceptable, even inevitable. Through a wide-ranging analysis of bridewealth and dowry systems, slavery, debt peonage, wage labour, and medieval service contracts, the lecture challenges the conventional opposition between free labour and unfree labour. It argues instead that wage labour historically emerged through processes of coercion, legal intervention, and moral inversion, often drawing directly on institutions of slavery and debt. From the standpoint of contemporary debates on precarity, platform work, and the service economy, the lecture appears not as a historical curiosity but as a critical framework for understanding the moral foundations of modern labour regimes. The review situates the lecture as one of Graeber’s most ambitious spoken syntheses, combining empirical breadth with conceptual clarity, and highlights its continuing relevance for analysing capitalism, freedom, and obligation in the twenty-first century.

Keywords

David Graeber; debt; wage labour; service; commoditisation of labour; economic anthropology; capitalism; moral economy; slavery; dependency

How Debt Taught People to Work: David Graeber on the Origins of Capitalism

The lecture by David Graeber, delivered on 9 June 2018 at the University of Birmingham as part of the Birmingham Research Institute of History and Cultures’ interdisciplinary conference Debt: 5,000 Years and Counting, stands in 2026 as one of the most generous, ambitious, and quietly radical syntheses of his intellectual project. Available on YouTube under the title David Graeber on Debt, Service, and the Origins of Capitalism, the talk captures Graeber at his most characteristic: disarmingly informal in delivery, meticulous in historical detail, and conceptually daring in the connections it draws across anthropology, economic history, legal theory, and moral philosophy. Graeber opens with a characteristically self-effacing remark, noting that he finished writing the paper at four in the morning and has not yet reread it. This moment of apparent casualness is not an aside but an important signal of method. The lecture is presented not as a closed system of claims but as an exploratory synthesis, an attempt to bring together strands of research that are usually treated in isolation. Rather than simply rehearsing arguments from Debt: The First 5,000 Years (2011) or offering a preview of Bullshit Jobs (2018), Graeber explicitly sets out to relate his long-standing analysis of debt to a broader genealogy of labour, and particularly wage labour, a subject he notes has been surprisingly under-theorised given its centrality to modern life.

The first major movement of the lecture revisits debates in economic anthropology around bridewealth, bride price, and dowry. Graeber situates this discussion within the history of anthropological intervention itself, recalling how early twentieth-century debates—most notably those surrounding the League of Nations—turned on the question of whether bride price should be treated as a form of slavery. Drawing on figures such as Evans-Pritchard, he outlines the classic argument that bridewealth payments are not literal purchases of women but complex exchanges that establish enduring social relations between kin groups. These arrangements, he stresses, involve mutual rights and responsibilities that fundamentally distinguish them from commodity transactions. Graeber then turns to Jack Goody’s influential distinction between bridewealth systems, common in much of Africa, and dowry systems, characteristic of Eurasia. He treats Goody’s work with evident respect, presenting it as one of the most compelling materialist explanations of marriage systems ever produced. Goody’s core insight—that differences in agricultural technology, population density, and labour requirements shape marriage payments—is carefully reconstructed. In societies where land is abundant and labour scarce, women’s agricultural labour becomes central, and bridewealth systems emerge as mechanisms for reallocating that labour between lineages. In contrast, in plough-based agricultural systems with dense populations and scarce land, dowry functions as a form of premature inheritance designed to consolidate property and manage demographic pressure. What gives Graeber’s intervention its distinctive force is his insistence that this framework remains incomplete without a sustained analysis of debt. He does not reject Goody’s model but extends it, arguing that debt has the power to transform social currencies into commercial ones, and in doing so to invert the meaning of social institutions. Marriage arrangements that once organised cooperation between groups can, under the pressure of monetised debt, begin to resemble outright commodification. This process, Graeber suggests, is not accidental but structural, and it has profound consequences for how women’s labour and bodies are valued.

Drawing on ethnographic material from Madagascar, as well as historical evidence from Mesopotamia, South Asia, and China, Graeber traces a recurring pattern: the commoditisation of poor women through debt, slavery, and wage labour is accompanied by the increasing seclusion and control of elite women. In early Mesopotamian sources, he notes, marriage payments initially functioned to provide women with portable wealth and a degree of economic autonomy. Over time, however, as commercial debt expanded and chattel slavery became conceptually salient, women could be alienated from their families as sureties for loans. Once that threshold was crossed, the language of marriage itself shifted, with bridewealth increasingly described as the ‘price of a virgin’ and illegal deflowering reclassified as a property crime. What makes this section of the lecture particularly compelling is Graeber’s refusal to moralise in a simplistic way. He does not present a story of linear decline but a complex account of how class relations among men were repeatedly mediated through women’s bodies. The greater seclusion of elite women emerges not as a sign of respect but as a reaction formation to the commoditisation of poorer women. Across Eurasian civilisations, Graeber observes, periods of intense commercial expansion tend to coincide with both increased trafficking in women and heightened anxieties about female purity and honour. Debt, in this account, functions as the key mechanism that allows people to accept arrangements they would otherwise find morally inconceivable. The second major movement of the lecture shifts from marriage systems to the history of wage labour itself. Graeber begins by noting a striking imbalance in historical scholarship: while slavery has generated an enormous literature, wage labour—despite being the dominant form of work in the modern world—has received comparatively little systematic attention. Where wage contracts do appear in historical sources, he argues, they are often embedded within discussions of slavery, and for good reason. In much of the ancient and medieval world, wage labour and slavery were not opposites but overlapping institutions.

In ancient Greece, Graeber explains, free citizens did not consider it shameful to work for wages when employed by the state or as mercenaries, but hiring oneself out to a private individual within one’s own community was widely regarded as degrading, effectively marking one as a slave. As a result, many early wage labour contracts turn out to have been contracts for slave rental. Slaves were hired out by their owners, or in some cases allowed to seek work independently while remitting a portion of their earnings. Similar arrangements, Graeber shows, characterised labour systems across the Indian Ocean world, from Madagascar to Southeast Asia, where port cities were populated largely by slaves and debt dependants who alone were willing or permitted to work for wages. These historical cases allow Graeber to advance one of the lecture’s most provocative claims: capitalism should be understood not as the antithesis of slavery but as a transformation of it. In mercantile city-states where finance, warfare, and commerce were tightly intertwined, dense concentrations of chattel slaves often coexisted with early forms of wage labour. Plantation slavery, he suggests, emerges precisely in these contexts, as a hybrid institution linking coerced labour, commercial production, and global trade. Debt once again plays a decisive role. In many societies, Graeber notes, individuals actively sought debt in order to render themselves dependent, since only dependants were considered suitable for ongoing wage labour. Debt peonage offered a status higher than that of vagrants or criminals, and debtors could be hired out by patrons who acted as intermediaries. The result was a world in which the same individuals could simultaneously be creditors and debtors, masters and servants, employers and employees, often within the same transaction. Far from being an anomaly, this ambiguity is presented as the historical norm. At the conceptual centre of this analysis lies what Graeber identifies as a fundamental paradox: the idea of a free contract between formally equal parties whose purpose is to create a relation of inequality. Debt contracts and wage labour contracts share this structure. Both rely on the extraordinary moral force of obligation to override other ethical considerations. From the vantage point of 2026, this insight resonates powerfully with contemporary debates about platform work, algorithmic management, and the rhetoric of choice that obscures relations of dependence.

The final major section of the lecture turns to Northern Europe, particularly England, where Graeber examines how ‘free’ wage labour became normalised in a society with relatively little chattel slavery in the late Middle Ages. Here his analysis of service proves crucial. Medieval service contracts, he shows, were typically yearly arrangements involving mutual obligations. Masters were expected to provide wages, food, and care regardless of whether work was available, while servants were bound to obey reasonable commands. Service was widely understood as a formative stage of life, a period of education and character formation through which young people accumulated resources to establish households of their own. Graeber traces how this system was gradually dismantled through enclosure, welfare legislation, and the expansion of master–servant law. As courts began to regulate labour relations in order to manage poor relief and enforce settlement rules, the service relationship was redefined around the principle of open-ended obedience. Employers’ authority was increasingly backed by the state, while workers’ status as creditors—having already performed labour—was systematically undermined. Legal doctrines allowed employers to withhold wages, impose fines, and even secure imprisonment for disobedience, effectively reversing the moral logic of the employment relationship. One of the lecture’s most striking conclusions is that modern ‘free’ labour required extensive government intervention to come into being. Far from emerging naturally from markets, wage labour had to be legally engineered through punitive measures that stripped workers of bargaining power. Graeber notes the irony that full contractual employment rights were first secured not by industrial workers but by clerical employees who fell outside master–servant law, a historical contingency that underscores the fragility and recentness of modern labour protections.

Graeber ends the lecture by gesturing toward the rise of the service economy and the commoditisation of thought and feeling, suggesting that the dynamics he has traced are now being extended into new domains. From the standpoint of 2026, this closing remark feels less like speculation than understatement. What the lecture offers, in retrospect, is not merely a historical account but a framework for understanding why debt remains such a powerful moral force, and why labour continues to be organised in ways that contradict the language of freedom used to describe it. As a spoken intervention, recorded and circulated online, this lecture exemplifies David Graeber’s rare ability to combine scholarly depth with public clarity. It stands as a testament to his insistence that economic arrangements are always moral arrangements, and that understanding their history is a prerequisite for imagining alternatives.

Conclusion: Debt, Work, and the Moral Illusion of Freedom

Viewed from today’s standpoint, this 2018 lecture reads less like a historical excursus and more like a diagnostic of the present. Many of the tendencies Graeber traced as long-term processes—the moral absolutism of debt, the normalisation of subordination through contract, the extension of service into ever more intimate domains of life—have since intensified rather than receded. What was once framed as the future of work has become a durable condition: precarious employment, algorithmic supervision, emotional and cognitive labour, and the persistent rebranding of dependency as choice. In this context, Graeber’s insistence that wage labour did not emerge naturally from markets, but was legally and morally engineered through debt, coercion, and state intervention, appears strikingly contemporary. The enduring value of the lecture lies in its refusal to accept the modern vocabulary of freedom at face value. By reconstructing how labour was historically detached from social obligation and reattached to monetary discipline, Graeber exposes the fragility of the moral assumptions that still underpin capitalist societies. His analysis suggests that the language of freedom surrounding work is not a description of social reality but a moral achievement—one that required centuries of institutional force and conceptual inversion to sustain. From today’s viewpoint, when labour increasingly resembles permanent probation rather than adulthood, this historical reminder acquires renewed urgency.

Equally important is the lecture’s methodological lesson. Graeber demonstrates that understanding contemporary capitalism requires moving across scales—between kinship systems and labour law, between ancient debt practices and modern employment contracts, between moral concepts and legal mechanisms. In doing so, he reclaims anthropology not as the study of distant others, but as a discipline capable of unsettling the taken-for-granted foundations of modern life. The lecture thus stands as a reminder that economic arrangements are never merely technical solutions to coordination problems, but moral settlements that shape what societies consider acceptable, inevitable, or unthinkable. From today’s perspective, Graeber’s closing gesture toward the service economy and the commoditisation of thought and feeling no longer reads as a speculative horizon. It names the condition in which many now live and work. The lecture’s lasting contribution is therefore not only historical insight, but moral clarity: a demonstration that debt’s power lies precisely in its ability to override other ethical frameworks, and that any serious reflection on labour, freedom, and dignity must begin by confronting that fact.

Bibliography

Graeber, D. (2018) David Graeber on Debt, Service, and the Origins of Capitalism. Lecture delivered at the University of Birmingham, Birmingham Research Institute of History and Cultures conference ‘Debt: 5,000 Years and Counting’, 9 June. Available on YouTube.

Graeber, D. (2001) Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of Our Own Dreams. New York: Palgrave.

Graeber, D. (2007) Possibilities: Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire. Oakland, CA: AK Press.

Graeber, D. (2009) Direct Action: An Ethnography. Oakland, CA: AK Press.

Graeber, D. (2011) Debt: The First 5,000 Years. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House.

Graeber, D. (2013) The Democracy Project: A History, a Crisis, a Movement. New York: Spiegel & Grau.

Graeber, D. (2015) The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House.

Graeber, D. (2018) Bullshit Jobs: A Theory. London: Allen Lane.

Graeber, D. and Wengrow, D. (2021) The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. London: Allen Lane.

About the Creator

Peter Ayolov

Peter Ayolov’s key contribution to media theory is the development of the "Propaganda 2.0" or the "manufacture of dissent" model, which he details in his 2024 book, The Economic Policy of Online Media: Manufacture of Dissent.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.