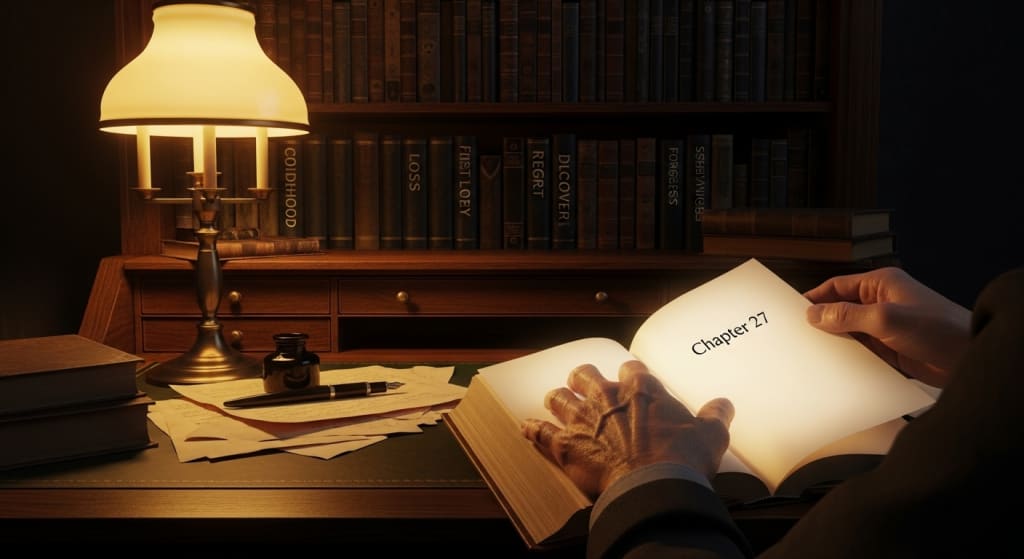

The Book of Us: Why Every Life Deserves to Be Written in Chapters, Not Judged by a Single Page

We Condemn Ourselves to Misery When We Forget That Stories Have Beginnings, Middles, and Endings

We are born into a story not of our choosing. The opening chapters are written by others—by parents who dreamed us before we existed, by circumstances that shaped us before we could shape anything back, by a world that assigned us roles before we knew we were on a stage. We arrive mid-sentence, in the middle of a tale that began long before our first breath, and we spend the rest of our lives trying to understand what kind of story we are in.

This is the great work of being human: learning to read our own lives as narratives, with all the complexity that entails. Every life is a book, thick and sprawling, filled with chapters that contradict one another, characters who enter and exit without warning, plot twists that make no sense until much later. And yet we insist on judging ourselves—and others—by single pages, as though a moment could stand for a lifetime, as though a mistake on page 94 cancels everything that came before or could come after.

The chapters of a life are not arbitrary divisions. They mark real transitions, real transformations, real endings and beginnings. There is the chapter of childhood wonder, when the world was new and every day held discovery. There is the chapter of adolescent longing, when love was agony and identity a question mark. There is the chapter of early adulthood, when we built careers and relationships on foundations we did not yet understand were shaky. There is the chapter of loss, when someone essential left and we learned that grief has its own geography. There is the chapter of midlife reckoning, when we looked back at the path taken and wondered about the roads not traveled. There is the chapter of acceptance, when we finally made peace with who we had become.

Each chapter is true. Each chapter is necessary. Each chapter contains versions of ourselves that we might now find embarrassing, painful, or unrecognizable—but they are us nonetheless, and denying them is denying the fullness of our own story.

The trouble begins when we forget this structure. When we mistake a single chapter for the whole book. When we read one terrible page and burn the entire volume. When we decide, based on a season of suffering, that the rest of our lives will be winter. When we look at another person and judge them by the worst thing they ever did, as though that moment defined every moment before and after. We do this constantly, to ourselves and to others, and it is a form of violence—a tearing of pages from a binding that was meant to hold them all.

Consider how differently we might live if we truly internalized the chaptered nature of existence. The mistake that haunts you, the failure that defines you in your own mind—what if you could see it as a single chapter, painful but finite, not the title of the book but just one passage among many? The person who hurt you, the one you have reduced to that single act of harm—what if you could imagine their whole story, the chapters that led to that moment and the chapters that followed, the complexity that every human life contains? The future that seems closed, the possibilities that appear exhausted—what if you understood that a new chapter is always waiting to begin, that the page can always turn?

I knew a man once who spent twenty years in prison for a crime committed in a single night of catastrophic poor judgment. When he emerged, he was not the same person who had entered. The chapters written inside those walls—of remorse, of education, of spiritual transformation, of quiet daily choices to become someone different—had rewritten him completely. But the world refused to read past the old chapter. Employers saw only the conviction. Neighbors saw only the ex-con. His own family, at first, saw only the shame they had carried for two decades. It took years of patient, consistent living for the new chapters to become visible to anyone but himself. He told me once, "I spent half my life becoming someone else, and most people still want to talk to the person I was at twenty-two." His eyes held no bitterness, only the exhaustion of being perpetually misread.

We are all him, in our own ways. We all carry chapters we wish we could tear out, pages stained with choices we cannot undo, passages we hope no one will read. And we all long to be seen in our entirety—not forgiven despite our worst chapters but understood as beings whose worst chapters are just one part of a much longer story. This is the deepest human hunger: to be known fully and still held dear. To have someone say, "I have read your whole book, and I am still here, still reading, still wanting to know what happens next."

The practice of living by chapters is not easy. It requires a kind of double vision: the ability to hold both the reality of a difficult chapter and the possibility of a different one to come. It requires resisting the tyranny of the present moment, which always wants to convince us that how things are is how things will always be. It requires extending to ourselves the same grace we would extend to a beloved character in a novel—the willingness to keep turning pages, to trust that the author (even when the author is us) knows what they are doing.

There is liberation in this perspective. The chapter that is crushing you now—the grief, the failure, the loneliness, the regret—becomes bearable when you remember that chapters end. Not because the pain is erased, but because it is placed in context. The darkest night of the soul is still just a night; morning comes, as it always does, as it always has. The mistake that feels definitive is still just a moment; other moments will follow, other choices will be made, other pages will be written. The relationship that ended painfully is still just a chapter in the longer story of your capacity to love; that capacity remains, ready to write again.

And there is responsibility in this perspective as well. If life is a book, we are its authors—not of the opening chapters, perhaps, but of everything that follows. The page is blank. The pen is in our hand. What will we write today? What kind of character will we choose to be in this new chapter? The answer is not determined by what came before. The past is written, but the future is unwritten, and the transition from one to the other happens in this very moment, in the choice we make now about who we are becoming.

The people around us are also writing their own books, chapter by chapter. The colleague who frustrates you is in the middle of a chapter you cannot see. The stranger who cuts you off is carrying chapters of urgency or fear you will never know. The enemy who harmed you has a story too, and while that story does not excuse their actions, remembering that it exists is the first step toward the kind of understanding that might, eventually, become something like peace. We are all protagonists of our own narratives, and we all believe, rightly, that our stories deserve to be read in full.

The great spiritual traditions have always understood this, in their way. They speak of redemption, of transformation, of the possibility that the worst sinner can become the greatest saint. They recognize that identity is not fixed, that the self is a river, not a stone, that who we were is not who we are and certainly not who we will be. This is the wisdom encoded in the metaphor of chapters: that change is real, that growth is possible, that the story is not over until it is over, and even then, it lives on in the stories it touched.

So here is the question that matters: What chapter are you in right now? Not the chapter you wish you were in, not the chapter you think you should be in, but the actual chapter that today represents. Name it honestly. Is it a chapter of healing? Of waiting? Of struggling? Of quiet contentment? Of painful transition? Of unexpected joy? Whatever it is, honor it. Live fully inside it. Learn what it has to teach. And trust that when it is complete, the next chapter will begin—not because you forced it, but because that is how stories work.

And here is the harder question: Can you read others with the same grace? Can you see that the person who hurt you is in a chapter you do not understand? Can you extend to them the possibility of change, even if you cannot extend forgiveness yet? Can you hold the complexity of a human life—your own, anyone's—without reducing it to a single page?

The book of us is vast. It contains multitudes, contradictions, failures, and glories. It is worth reading carefully, all the way through, with patience for the slow parts and courage for the hard parts and hope for the parts still to come. The chapter you are in right now is not the whole story. Turn the page. See what happens next. The pen is still in your hand

About the Creator

HAADI

Dark Side Of Our Society

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.