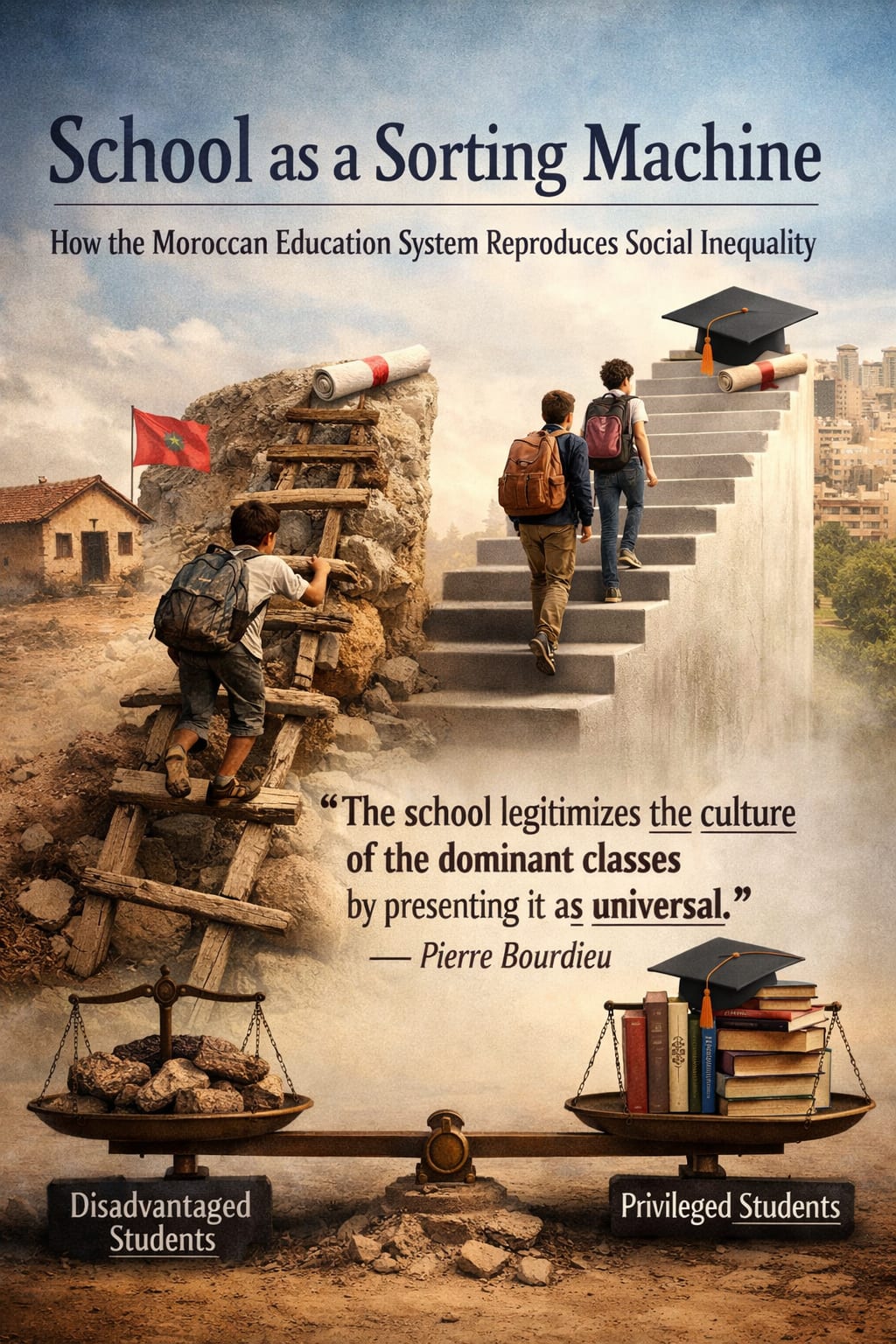

School as a Sorting Machine

How the Moroccan Education System Reproduces Social Inequality Instead of Reducing It

Education is often presented as the most powerful instrument of social mobility, a neutral arena where merit prevails over origin. In Morocco, as in many postcolonial societies, schooling is officially framed as a republican promise: equal opportunity for all citizens regardless of class, geography, or family background. Yet, behind this discourse lies a deeply stratified educational system that systematically disadvantages students from poor, rural, and working-class backgrounds. Rather than correcting social inequalities, the Moroccan education system frequently reproduces and legitimizes them. This discrimination has severe social, economic, and political consequences, and it raises an urgent question: how can Morocco move toward a genuinely egalitarian educational system?

________________________________________

Structural Discrimination in the Moroccan School System

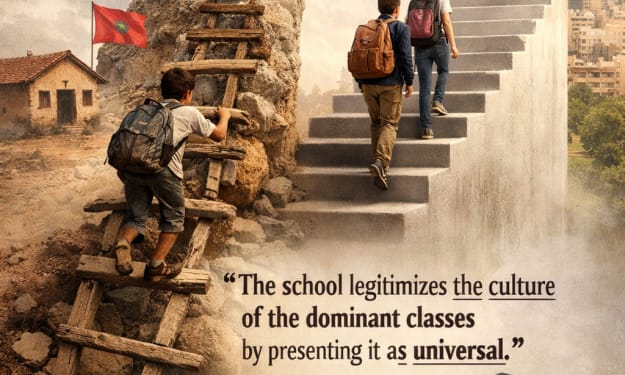

Discrimination in Moroccan education is not usually explicit or legal; it is structural. One of the most visible mechanisms is territorial inequality. Rural schools suffer from chronic shortages of qualified teachers, inadequate infrastructure, overcrowded classrooms, and limited access to digital tools. In contrast, urban schools—especially private institutions—offer smaller class sizes, extracurricular activities, language immersion, and exam preparation programs. From the earliest years of schooling, students do not start from the same line.

Language policy further exacerbates inequality. Moroccan public education relies heavily on Arabic and French, while elite private schools increasingly emphasize French and English as languages of instruction. Students from disadvantaged backgrounds, whose families often lack linguistic capital in foreign languages, struggle to adapt. As sociologist Pierre Bourdieu famously argued, “The school legitimizes the culture of the dominant classes by presenting it as universal.” In Morocco, mastery of French or English is treated as a neutral academic skill, when in reality it reflects unequal social inheritance.

The expansion of private education has intensified this divide. While private schools are presented as a solution to the “crisis” of public education, they effectively create a two-tier system: one school for the wealthy and another for the poor. Public schools become residual institutions for those who cannot pay, reinforcing stigma and lowering expectations.

________________________________________

Cultural Capital and the Myth of Meritocracy

Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital is particularly relevant to the Moroccan context. According to Bourdieu, students from privileged families possess linguistic styles, cultural references, and modes of behavior that align with school expectations. Teachers, often unconsciously, reward these traits, interpreting them as intelligence or motivation.

In Morocco, students from disadvantaged backgrounds may be equally capable but unfamiliar with academic discourse, exam strategies, or implicit classroom norms. When they fail, the system attributes their failure to individual effort rather than structural disadvantage. As Bourdieu and Passeron wrote in Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, “Academic success is largely dependent on the cultural capital transmitted by the family.” The Moroccan school system thus transforms social inequality into academic inequality and then presents it as meritocratic.

Educator Paulo Freire also criticized such systems, arguing that traditional schooling often functions as a form of symbolic domination. For Freire, education that ignores students’ social realities becomes an instrument of exclusion rather than liberation. Moroccan curricula, largely centralized and standardized, rarely reflect the lived experiences of rural or working-class students, further alienating them from learning.

________________________________________

Consequences of Educational Discrimination

The consequences of this discrimination are profound. On an individual level, many students from disadvantaged backgrounds experience early school dropout, low self-esteem, and a sense of failure internalized as personal inadequacy. On a collective level, educational inequality perpetuates social immobility, unemployment, and intergenerational poverty.

Economically, Morocco loses a significant portion of its human potential. Talented students are filtered out not because of lack of ability, but because of lack of resources. Politically, persistent inequality undermines trust in public institutions. When education fails to deliver fairness, it fuels frustration, disengagement, and sometimes radicalization.

Moreover, the symbolic violence described by Bourdieu—the process through which domination is perceived as legitimate—leads many disadvantaged students to accept their position as “normal.” This silent acceptance is perhaps the most damaging outcome, as it neutralizes demands for change.

________________________________________

Toward an Egalitarian Educational System

Creating an egalitarian education system in Morocco requires structural, pedagogical, and ideological reforms. First, massive investment in public education is essential, particularly in rural and marginalized areas. Equal funding, teacher training, and infrastructure must be non-negotiable principles.

Second, language policy should be rethought. Rather than using foreign languages as hidden filters of social class, Morocco could adopt more inclusive bilingual or multilingual models that support students linguistically instead of penalizing them.

Third, teacher training should include sociological awareness. Educators must be trained to recognize how social background affects learning and assessment. As Bourdieu insisted, neutrality in unequal systems only reinforces inequality.

Finally, education must be reimagined not as a mechanism of selection, but as a public good aimed at emancipation. This means valuing diverse forms of knowledge, connecting curricula to students’ realities, and restoring dignity to public schooling.

________________________________________

Conclusion

The Moroccan education system does not merely reflect social inequality; it actively participates in its reproduction. Through unequal resources, linguistic hierarchies, and the myth of meritocracy, it discriminates against students from disadvantaged backgrounds while masking this discrimination as fairness. Drawing on the insights of sociologists like Pierre Bourdieu and educators like Paulo Freire reveals that true educational reform is not only technical, but deeply political. An egalitarian education system is possible—but only if Morocco chooses justice over convenience and equality over illusion.

About the Creator

Rachid Zidine

High School Teacher

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.