The Forgotten Half: Why We Teach Everything Except How to Be Human

We Fill Children's Minds with Facts and Formulas but Leave Their Hearts Empty—and Wonder Why They Feel Lost

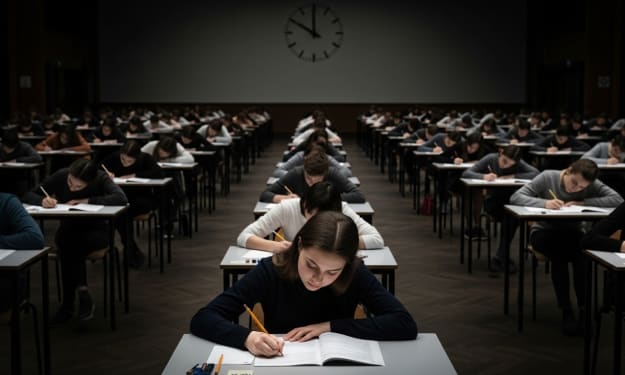

There is a curriculum we teach, and there is a curriculum we ignore. The first is written in standards and textbooks, measured by tests and grades, celebrated in awards and acceptances. It includes mathematics and literature, science and history, the accumulated knowledge of centuries passed from one generation to the next. This curriculum is important. It opens doors, builds skills, creates the foundation for careers and contributions. We have become very good at teaching it.

The second curriculum is unwritten. It includes how to sit with someone who is grieving. How to know what you feel and what to do with it. How to disagree without destroying. How to apologize. How to set boundaries. How to ask for help. How to be alone without being lonely. How to love. How to fail and get up again. How to find meaning when the world stops making sense. This curriculum is essential. It determines the quality of our relationships, our resilience in crisis, our capacity for joy. And we barely teach it at all.

We send children into the world with heads full of information and hearts untended, and then we wonder why so many of them struggle, why anxiety and depression have become epidemic, why relationships fracture, why meaning feels elusive. We have educated the mind and neglected the soul, and the imbalance is destroying us. The most important things cannot be tested, so we have decided they cannot be taught. This is a catastrophic error.

The child who can solve complex equations but cannot name their own emotions will struggle in every relationship they enter. The teenager who knows every historical date but has no tools for processing grief will be overwhelmed when loss comes—and it always comes. The young adult who has been trained to achieve but never taught to reflect will climb ladders only to discover they are leaning against the wrong walls. The graduate who has been graded on every paper but never encouraged to ask what they care about will spend decades chasing success that feels empty.

These are not failures of the students. They are failures of the system. We have built schools that treat human beings as future workers rather than whole people, that value measurable outputs over immeasurable growth, that prioritize what is useful for the economy over what is essential for the soul. And we have done this so thoroughly, for so long, that we have forgotten there was ever another way.

There was another way, once. In older traditions, education was always formation—the shaping of the whole person, not just the mind. The Greeks spoke of paideia, the cultivation of excellence in body, mind, and character. Indigenous cultures taught children not just skills but stories, not just facts but relationships—to the land, to the community, to the ancestors. Religious traditions educated the heart through ritual, contemplation, and moral instruction. These approaches understood something we have forgotten: that knowledge without wisdom is dangerous, that achievement without character is hollow, that the unexamined life is not worth living.

The modern school emerged from different priorities. It was designed during the Industrial Revolution to produce workers for factories and clerks for offices. It valued compliance, punctuality, the ability to perform specified tasks on demand. These were useful qualities for the economy of that time. They are less useful now, and they were never sufficient for the full flourishing of human beings. But the model persists, inertia masquerading as inevitability, because changing it would require us to ask hard questions about what education is actually for.

What if we asked those questions honestly? What if we designed schools not around what is easiest to measure but around what matters most? What if we taught children not just how to read but what books can mean in a life? Not just how to calculate but how to think about what is worth calculating? Not just the dates of wars but the experience of those who fought them, those who fled them, those who lost everything? Not just the facts of science but the wonder of it, the awe of understanding how the universe works? Not just skills for careers but tools for living—how to listen, how to grieve, how to forgive, how to hope?

There are schools that try. They carve out time for circle discussions where students share what is really going on in their lives. They teach mindfulness and emotional literacy alongside mathematics. They prioritize project-based learning that requires collaboration, communication, and persistence. They assess not just what students know but who they are becoming. These schools are often dismissed as experimental, as soft, as insufficiently rigorous. But their graduates are different—more self-aware, more resilient, more capable of navigating the complexity of actual human life. They have been educated, not just trained.

The resistance to this kind of education comes from fear. Fear that if we spend time on emotional learning, academic achievement will suffer. Fear that if we teach children to question, they will question us. Fear that if we attend to the heart, the mind will be neglected. These fears are understandable but unfounded. The evidence shows that social-emotional learning improves academic outcomes, that children who feel safe and seen learn better, that the whole person approach produces not weaker students but stronger humans. The fears are not about effectiveness; they are about control. They are about maintaining a system that sorts and ranks rather than one that nurtures and liberates.

What would it take to change? It would take courage—the courage to admit that we have been measuring the wrong things, that the most important outcomes cannot be quantified, that the purpose of education is not economic productivity but human flourishing. It would take imagination—the willingness to envision schools that look nothing like the ones we attended, that prioritize different goals, that value different achievements. It would take patience—the recognition that the fruits of this kind of education appear over decades, not in quarterly test scores, that the child who learns to be human today will be a better parent, partner, citizen, and worker for the rest of their life.

Most of all, it would require us to change how we see children. Not as future workers to be trained, not as test scores to be raised, not as college applications to be polished. But as human beings in their own right, with inner lives as rich and complex as our own, with questions that matter, with pain that deserves attention, with potential that extends far beyond any metric we can devise. Children are not projects. They are people. And people need more than facts. They need to know how to live.

The classroom split by light is a choice. On one side, the equations, the dates, the measured achievements. On the other, the empty circle, the wildflower, the garden waiting. We have spent a century building the first side. It is time to turn toward the second. Not to abandon the first—knowledge matters, skills matter, achievement matters. But to balance it, to complete it, to remember that the point of education is not to fill a bucket but to light a fire, and that fire burns not in the mind alone but in the whole human being.

The child who learns to solve for x but never learns to sit with sorrow will solve many equations and still feel empty. The teenager who masters every formula but never learns to listen will succeed at many things and still be alone. The graduate who achieves every goal but never learns what they care about will climb every ladder and still wonder why the view from the top is so disappointing. We are doing this to them. We are building the first side of the classroom and leaving the second side empty. And then we wonder why they struggle.

The garden is waiting. The circle is empty. The wildflower has fallen on the floor. The question is whether we will finally have the wisdom to open that door, to invite our children into that space, to teach them not just how to make a living but how to make a life. The forgotten half of education is waiting to be remembered. The whole child is waiting to be seen. The future is waiting to be different. Let us begin.

About the Creator

HAADI

Dark Side Of Our Society

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.