Pioneer From Afar

One day our message will be read - far, far away

Yesterday, the Sun was rising in the west when we set off from the observatory in our recovery vehicle in search of whatever it was that came down in the desert during the previous night. The three of us - Yoglan, Zibor and I (my name is Nesgan) – are astronomers who regularly scan the data for signs of approaching objects that could threaten the planet. The larger ones are monitored on a constant basis, and craft are sent to intercept and destroy them on the rare occasions when they could spell disaster, and smaller objects are left to burn up in the atmosphere should they get that close.

However, the one we were looking for yesterday was a different matter. We had spotted it some time ago and could tell that it was not the usual lump of rock that has been drifting through space ever since the planets were formed. It gave every impression of being some sort of artificial satellite, but it was clearly not one that we had launched, nor could it be an unmanned probe returning from a mission to deep space. Its trajectory showed that it would pass within 200,000 plogols of our planet, which was well within range of an interceptor mission if we launched one in time, which we had indeed done.

The mission had succeeded in its aim and encased the object in a module that had separated from the mother craft and been sent back in our direction. Not knowing what an object is, it is always preferable to take this course of action and not endanger our own vehicle. Capture modules are easily replaced, whereas mother craft are not.

The module had now parachuted down to the surface and our task was to find it, carry out a basic assessment and take it back to the observatory if we thought it was safe to do so.

It was not difficult to find. We simply followed the beacon signal sent out by the module and before long we could see the dark shape silhouetted against the bright green desert sand. During its descent the instruments inside the module had done their job and carried out an initial survey of the captured object, and once we were within range we could read the results on our monitors in the recovery vehicle. We therefore knew that nothing on the object was explosive and it did not carry any harmful microorganisms that could bring disease to our planet.

We quickly lifted the module into the cargo bay of our vehicle and headed back to the observatory. Today our task has been to open the module and see what it is that has apparently come such a long way.

Since it arrived we have been examining all the data we have available to track the object back to where it might have come from. Even given the massive power of the computers based at the observatory, it has taken all night for them to plot the course it must have taken. The result astounded us all. According to the data, our planet has revolved around the Sun more than two million times during the time that the craft has been on its way to us, but then another problem was brought to our attention.

This was that our telescopes could identify exactly which solar system the craft came from, but also failed to identify any planet in that system that could possibly have been responsible for launching it.

We simply had to open the module and see what was inside it, so that was what we did.

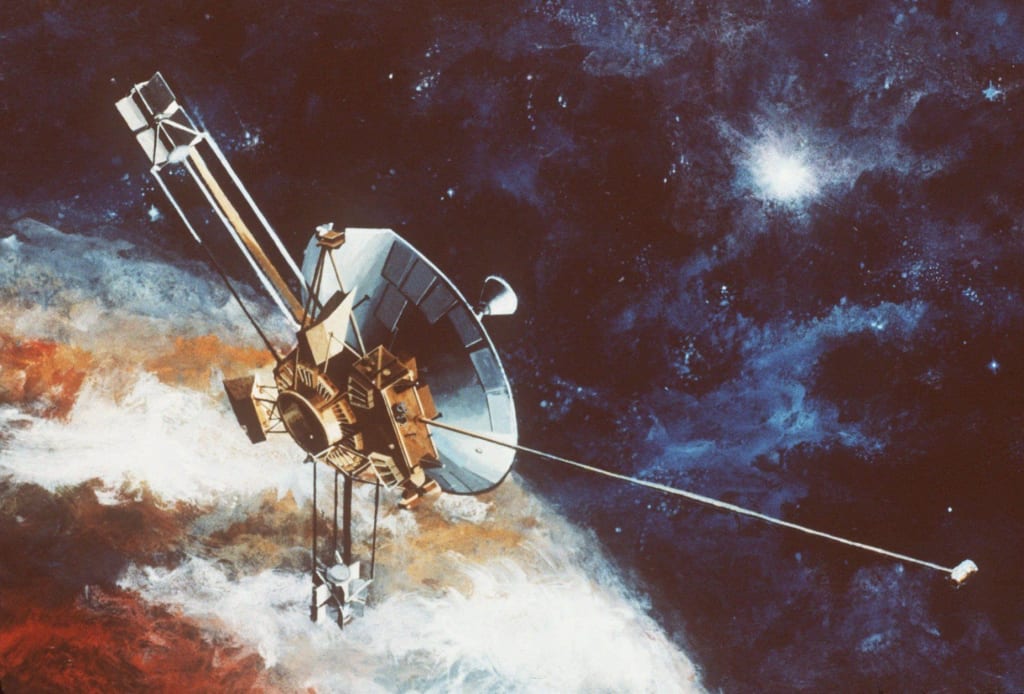

It was what I had suspected, namely a probe that carried a range of scientific instruments and transmission devices. These were absurdly primitive to our eyes, being the sort of thing that one read about in books of ancient history about how our remote ancestors first explored our own neighbouring planets. The mission of this craft had clearly been to gain data about planets other than the home planet, and about the space between the planets. After that, it would have headed out into deep space on its immensely long journey before it was captured by our module and landed in the desert just a few plogols away.

But which was the home planet?

This problem was solved when we found a plaque on the side of the probe that carried some very interesting information. This included coordinates that confirmed what we already knew, namely the location of the home star, and the very useful indication that the home planet was the third closest to the star.

But surely that is not possible? All the observations, allowing for the passage of time that the probe had been on its journey, and bearing in mind that all views of distant worlds have to allow for the time that light takes to reach us, show that none of the planets is even remotely capable of sustaining life.

A check back on our scans of that third planet have confirmed what we had always known, namely that there is precious little difference between it and the second planet. Both of them are encased in thick atmospheres consisting largely of carbon dioxide, methane and water vapour, all gases that would cause the surface to heat up to such an extent that all liquid water would evaporate and kill every living organism there might ever have been there.

Another point of interest on the plaque, which I am looking at now, is the depiction of two lifeforms which look remarkably like ourselves. One clearly resembles Zibor and me, the other is more like Yoglan were she to be undressed. It fascinates me to think that evolution has produced such similar results at such vast distances across the cosmos, although there are clearly a few differences.

So these two figures represent the higher lifeforms that sent this probe into space? From a planet that was uninhabitable? There is only one conclusion that I can reach. This is that the third planet on the plaque was indeed capable of sustaining intelligent life at the time the probe was launched, but it must have ceased to be that way within a very short time afterwards.

And by “a very short time” I mean almost no time at all in terms of how we astronomers calculate these things. I reckon that, when I make the calculation, I will find that the third planet cannot have circulated its star more than a hundred times after the probe was sent before disaster struck. I might be wrong by a few circulations either way, but surely not by all that many. Life would have become increasingly difficult after that time, with no way to avoid the ultimate catastrophe of the third planet turning into a carbon copy of the second – and “carbon” might indeed be the right word to use in this context.

Looking back at those two lifeforms on the plaque, I just wonder how intelligent they really were? They look as if their brain capacity should have been sufficient to work out how to manage their affairs so that they would not kill their planet, but was that actually the case?

Presumably the lifeforms who designed and sent the probe were not also responsible for the terrible decisions that led to ultimate destruction, but those others must have been incredibly stupid, despite having the same brain power as the planet’s clever people. Or maybe the stupidity lay with the ones who allowed the decision-makers to get to where they did.

I can imagine that there must have been plenty of clever lifeforms who could see the signs and pleaded with the stupid ones to see the error of their ways. What a shame they did not shout more loudly.

About the Creator

John Welford

John was a retired librarian, having spent most of his career in academic and industrial libraries.

He wrote on a number of subjects and also wrote stories as a member of the "Hinckley Scribblers".

Unfortunately John died in early July.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.