The walk to the killing lake was so much louder than usual today. The snow crunched under my feet, and the sound of the chains around my wrists was an unwelcome addition to the usual quiet. Every member of our small town was walking through the trees with me, but they were silent. Only their footsteps and the occasional quiet sob could be heard.

Our Occupiers surrounded us, their weapons leaving no room for argument. I should have known better. I should have known that resistance could only ever end one way. Now, on this final trek to the killing lake, I suddenly felt more alive than ever before. The colors were all so bright. The deep green of the pine trees, and the usually dull fabrics my people used to clothe themselves.

My skin felt the cold now more bitingly than ever, even though we were no longer in the dead of winter. The walk seemed longer somehow than all the other marches to the killing lake. I guess it was different when it was your turn to die.

It hadn’t always been called the killing lake. Once, it was just a place to be alive, to laugh and swim and chase and be chased. Once, I had pushed my brother off a tall rock into its depths, and he had surfaced seconds later, laughing even as he threatened revenge. That was before they arrived, with their powerful force and their will; more ruthless than ours. That was before I grew from a child into a spy.

My parents walked beside me, my father supporting my mother as we drew nearer to my judgment. My brother had taken his last walk to the killing lake over a year ago now, for trying to free us from our Occupier’s iron grip. He hadn’t succeeded, and neither had I. As I glanced at my mother, I wondered if it was better that after today, she wouldn’t have to watch any more of her children walk across the killing lake.

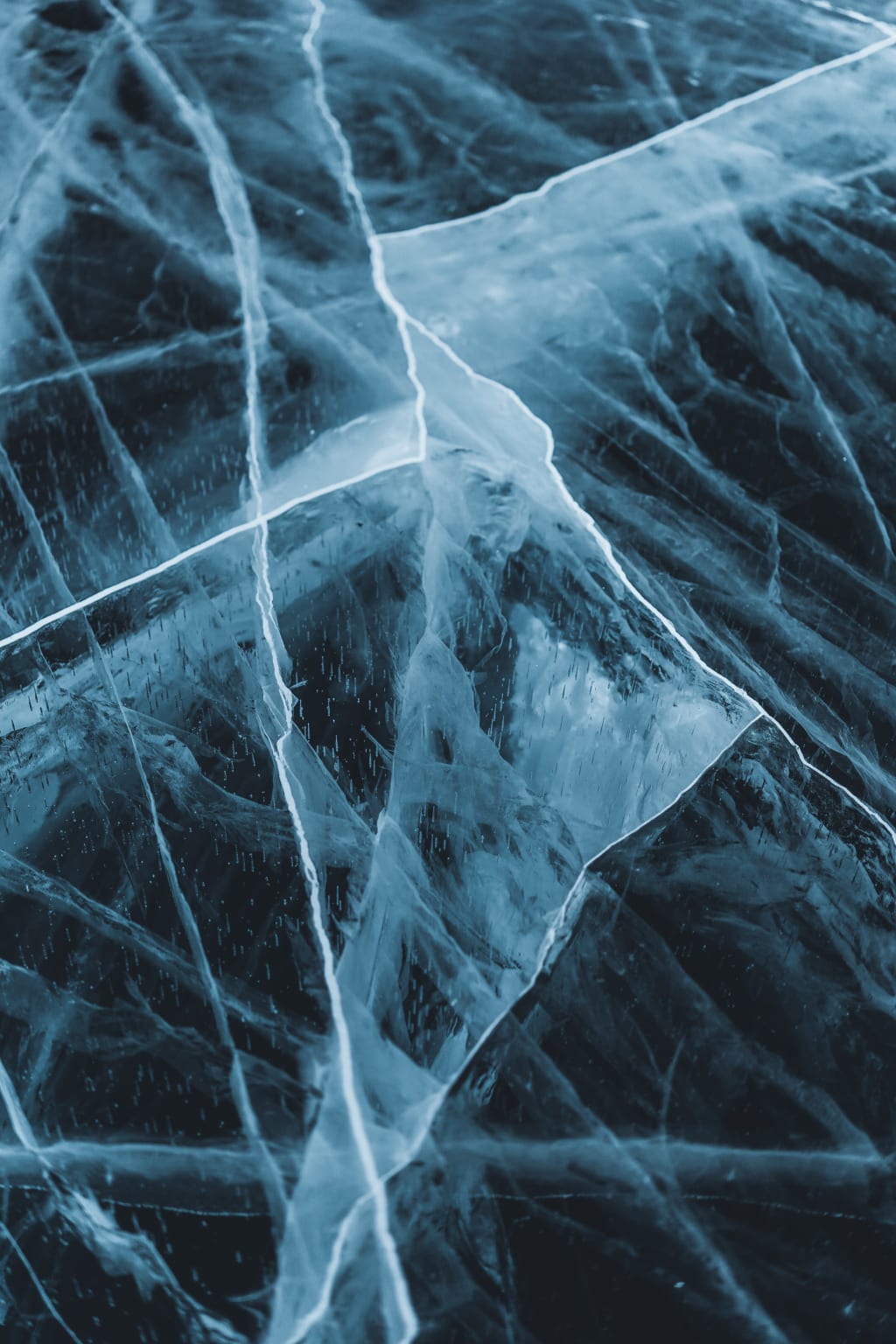

The trees parted, just as they always did on our marches here, but this time, I was the one stepping up to the frozen edge. None of my people spoke. Their protests of this ritual had been beaten out of them years ago.

The Judge approached me, and the way he towered over me was no longer intimidating or terrifying like it used to be. He wasn’t really a judge, just a military captain given the power to use and abuse us. He spoke the way he always did at the edge of the killing lake as he removed the manacles encircling my wrists. “The lake will be your judge.” He said. “Walk across to the other side, and you will be free.”

It sounded so simple, like there was a good chance I would make it across, but we all knew better. I should have hated the Judge, and the rest of the men who occupied our town, forcing us to walk across the killing lake whenever we got out of line. I should have hated them for only using this punishment as winter came and went, and not when the lake was frozen solid.

Instead, I took one last glance back at my parents. They both looked resolute, faces set and strong. The rest of my people watched me with the same resolve. This was always our way at the killing lake. Lending our strength to whoever was walking across the ice. Today I was grateful for it. My father nodded. I nodded back and stepped out onto the cold surface of the lake.

The Occupiers disappeared. My people and my family disappeared, and so did any lingering fear. All that was left now was me, the ice, and all the moments of my life that had led up to this point. I took another step, and the ice held beneath me.

The smell of the pine trees surrounding the lake came to me more sharply than before, as if my senses were trying to get the most out of the time they had left. The smell reminded me of long walks in the forest with my father. He used to let me bring a bow and hunt for small animals, pointing out which plants were safe to eat. We would spend all day in the quiet forest, heading home before dark to find my mother had prepared a rich soup or stew. I took a few more measured steps, and the ice held beneath me.

The killing lake was deep all the way around. So many of my people slept beneath the ice under my feet. I silently noted each point I passed as I walked, where someone else had fallen through the ice. Here was where my schoolteacher fell through. She had always been austere and strict, but when the Occupiers came, she was the first to step between us and their fists. She hadn’t made it very far across the killing lake. Even worse, that was back when my people were still raw and afraid, screaming their fear at each step she took. We hadn’t yet learned to lend each other our strength.

A few steps further, and I reached the place where the butcher fell through the ice. There was a year where the winter was particularly brutal. The children were starving, me included, and there wasn’t enough food because the Occupiers had taken it all. My brother and I found a frozen pond beyond the town, and almost lost our fingers to frostbite searching through it for hibernating frogs that we might be able to eat. The butcher took his walk to the killing lake after he slaughtered a few animals without permission, allowing us to survive the last few weeks of winter.

I looked down as the ice continued to hold, searching for cracks that weren’t there. Pressing on, I reached the spot where my brother fell through the ice. That had been the hardest one to bear. My brother protected me. When the Occupiers came, he turned angry and defiant. He stopped teasing me and started to find a way to resist. It started with kids carrying messages from town to town in the dead of night. For my brother, it ended when the Judge’s house went up in flames, nearly killing his family. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t proud of my brother. Right up until the moment where, standing right where I was standing, he fell through the ice of the killing lake.

On that day, I became the angry one. I became the one passing information to our children, trying to get messages to towns far away. Trying to find help or send help. Anything to free us. Anything to stop watching my people starve. I took a few more steps. Beneath my feet, tiny veinlike cracks began to form. They whispered their way through the ice, delicate and unassuming.

It didn’t matter. I kept walking, like everyone before me. My brother walked without stopping, even as we heard the sharp cracks of the ice breaking beneath him, and so would I. The Judge had been suspicious of me for months, even up until the coldest part of the winter. I could have stopped sabotaging his correspondence and making sure only rotting meat made its way to his table, but I didn’t.

I was always going to wind up at the killing lake eventually. I’d known it since my brother took his walk. I didn’t want to die. I hadn’t wanted him or anyone else to die either. But in these final moments, I had to believe that the sum of all our walks to the killing lake would add up to our freedom, no matter how long it took.

The sharp crack beneath my feet was swift and sure, the cold rushed up, and the killing lake made its judgement.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.