Ghost Time Theory - We Live in the Past

Understanding the Delay Between Perception and Reality

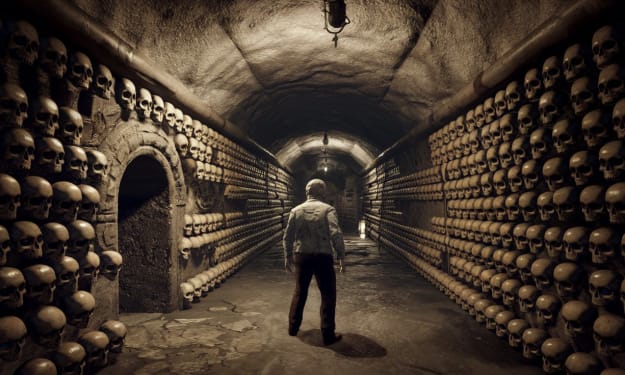

In the year 1752, specifically on the first of September, a young man, known in his village for his cleverness and cunning, and his love for betting, heard in the morning of this day from his workplace in the neighboring village some news from a traveling merchant. He was certain that no one in his village knew about it. This news was strange, surprising, even exceptional, and it would not happen again. A person with his cunning and shrewdness would not let it pass without taking advantage of it. He thought for a moment, then the idea struck him. He quickly ran through the village’s alleys, calling on the villagers to hurry and gather in the village square because he had brought them a bet. The challenge was impossible to win, but he wouldn’t lose it.

When they gathered, he spoke to them saying: “You love challenges, and most of you wish I would lose even one bet. If you are interested and looking for the impossible bet, I have brought it to you. I can dance in front of you for twelve days and nights continuously without stopping, neither for drinking nor eating. If you think it’s madness and physically impossible for me to endure and succeed in this, place your money on this bet. If I win it, the money will be mine.”

Everyone laughed mockingly, looking at him like he was crazy and said, “Maybe he’ll lose this time.” The young man said, "We have agreed to meet tomorrow, on the second of September, I will start dancing at night and continue until the fourteenth of September, and you will bear witness to it."

Indeed, the young man won the impossible bet again amidst the astonishment of the villagers. Yes, he danced continuously for twelve days and nights and won the bet. The bet money was now his.

If you’re now looking for a solution to this puzzle, take a deep breath and listen carefully because the answer lies in an ancient and real legal case that hides something even stranger, possibly involving conspiracies.

This theory, the Phantom Time Hypothesis, has recently spread on social media with posts about missing days from certain years in the Gregorian calendar. This is not a new topic, but whenever it resurfaces, it brings with it a conspiracy theory. Many might think it’s closer to fiction than reality, but its proponents are convinced it’s true. You’ll learn more about it in the context of the story, but first, let’s look at the reason why this theory arose.

I believe many of you have come across a post talking about the missing 11 days in September 1752, and perhaps some of you even searched for this calendar on Google and found the truth. The reality of this event is true and has indeed occurred. But these days weren’t the only ones lost, and it wasn’t the first time.

Let’s rewind to February 1582, when the Gregorian calendar was adopted instead of the Julian calendar by the Catholic Church. The Julian calendar had been in use since 2 BC and was created by Julius Caesar. This calendar had been in use for many centuries, but it had many flaws, notably an error of 11 minutes, which caused the solar year to be 11 minutes longer than it should have been, leading to a drift of one day every 18 years. This drift caused errors in determining the date of Easter, and in the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, it was agreed that Easter should fall on the Sunday after the first full moon following the vernal equinox.

But due to this drift, it became difficult for the Church, and voices were raised asking for a solution to this problem. Discussions and proposals began from 1562 to 1582, and in February of that year, Pope Gregory XIII introduced what he called the “papal revolution.” The Gregorian calendar came into being based on the suggestions of the Italian scientist Luigi Lilio, with some adjustments by the mathematician and astronomer Christopher Clavius. To solve the problem, it was decided to delete days from the Julian calendar.

If the goal was to stabilize the days according to the vernal equinox to align with Easter celebrations, logically, 10 days in March should have been removed to return the equinox from March 11 to the 21st. But the Church had a different opinion, and it refused to delete days from March to avoid interrupting major Christian holidays. Instead, 10 days were removed from October, so the new October of 1582 looked like this: October 1, 2, 3, 4, and then directly October 15, continuing through the rest of the month. Thus, the problem was solved, and the Gregorian calendar became the standard from that point on.

Historical sources show that European countries did not adopt the Gregorian calendar all at once. The first countries to adopt it were France, Italy, Poland, Portugal, and Spain. However, Britain did not adopt it until 1750, and after lengthy discussions, the British Empire agreed to use the new calendar. The problem arose because of the difference between countries that had adopted the calendar early and Britain. To unify the calendar and eliminate the discrepancies, it was decided to correct the gap by deleting 11 days from September. Thus, September 1752 ended on the 2nd, and resumed again on the 14th.

Japan also joined in 1872, deleting 12 days from December, and Turkey was the last country to adopt the Gregorian calendar, starting on January 1, 1927.

Yes, there were days lost in history. But before we reach the shocking and controversial part, there are funny stories related to this event. For example, early on, the British thought this change and deletion of days meant they lost 11 days of their lives, so they launched a campaign called “Give Us Back Our 11 Days.”

In a book by author W. M. Jemison, there’s a funny story about a man named William Wilter of London. He made a bet with the villagers that he could dance for three days and nights continuously, and indeed, he started his dance around the village on the night of September 2, 1752, and stopped dancing on the morning of September 14. He won the bet and took the money, to the amazement of the villagers."

In the book by author W. M. Jemison, there’s a funny story about a man named William Wilter of London. He made a bet with the villagers that he could dance for three days and nights continuously, and indeed, he started his dance around the village on the night of September 2, 1752, and stopped dancing on the morning of September 14. He won the bet and took the money, to the amazement of the villagers. However, the villagers were unaware that this period had been altered by the missing 11 days, so the villagers thought they had lost those days while William Wilter was dancing, adding an extra layer of confusion and amusement to the situation.

The deletion of 11 days in September 1752 raised significant doubts and questions. Many people thought that the calendar had been tampered with, that something was deliberately hidden, or that the days had been stolen from them. The conspiracy theory arose from the confusion about the calendar change and the feeling that time itself had been manipulated.

As we now know, this change was not just a random alteration, but a necessary adjustment to account for the inaccuracies of the Julian calendar. It was essential to prevent further drifting of the dates, but for those who lived through it, it felt like a strange and mysterious event. The Phantom Time Hypothesis, which proposes that parts of history were fabricated or erased, partly grew out of this skepticism about missing time.

In conclusion, while the missing days of September 1752 are an interesting historical anomaly and a source of curiosity, they were part of a larger reform aimed at standardizing time. The event also shows how even seemingly simple changes in our calendar system can become fodder for myths, speculation, and conspiracy theories. Today, we live in a world where these 11 days are acknowledged as a part of the historical record, but their true significance remains a topic of ongoing interest and mystery.

The story we began with regarding William Wilter, who made the bet with the villagers that he could dance for three days and nights continuously, did indeed happen. He began dancing around the village on the evening of September 2, 1752, and did not stop until the morning of September 14. He had won the bet, and naturally, the money from the wager became his. The villagers were in shock. But what they didn't know was that the calendar change meant that time had been altered in a way that led them to think the days had somehow been lost.

What they didn't realize was that the deletion of these 11 days was part of the changeover from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar, which had been introduced earlier by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582. This was a correction to the year-length discrepancy that had been accumulating due to the Julian calendar's minor miscalculation of the length of the solar year. Over centuries, this error caused the dates to drift, leading to confusion over when events like Easter should be celebrated.

As the years passed, different countries adopted the new Gregorian calendar, but there was resistance, especially in Britain, which did not officially adopt it until 1752. To align the British calendar with the Gregorian system, 11 days were "dropped" from the month of September that year. This meant that the date moved directly from September 2 to September 14, 1752. The British population felt that they had lost time, and many thought they were being cheated out of those 11 days.

This led to confusion and even conspiracy theories. In fact, some individuals started to question the accuracy of history itself, and the idea that time had been manipulated gained traction. The "Phantom Time Hypothesis," which asserts that certain historical periods were fabricated or erased, is one of the theories that arose from these events.

The hypothesis suggests that certain periods, especially from the 6th to 10th centuries, were deliberately inserted into history. It also claims that the years from 614 to 911 AD are entirely fictional. According to this theory, a number of powerful figures from the time — such as Pope Sylvester II, Holy Roman Emperor Otto III, and Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII — are said to have conspired to alter the calendar to serve their purposes. The idea was to make the year 1000 seem more significant for the Christian world, positioning it as a time of spiritual and historical importance.

Those who support this theory claim that historical documents from this era, such as records from the Byzantine Empire, are fabricated and that the events of the time were entirely invented to serve the political and religious agendas of these figures. According to these proponents, the Middle Ages as we know it — and especially the "Dark Ages" — may not have existed at all.

While this theory is certainly extreme and controversial, it has gained attention in some circles, especially among conspiracy theorists. The question, though, remains: is it possible that history was manipulated to such an extent that we are living in a century that never happened?

Of course, many historians and scholars have thoroughly debunked the Phantom Time Hypothesis. They argue that it relies on selective evidence and overlooks the extensive historical documentation from other cultures and civilizations, including in Asia and Africa, which align with the accepted timeline of history. Moreover, astronomical observations, such as solar eclipses, have been recorded and verified in various regions, further supporting the accuracy of the calendar system.

Furthermore, the Islamic world and its rich history, from the time of the Prophet Muhammad to the spread of Islam, provide substantial evidence that the years in question were indeed accurate. The birth of Islam, the Hijra (migration of the Prophet), and the subsequent expansion of the Muslim empire occurred within the timeline that is consistent with both Islamic and global historical records.

In conclusion, while the Phantom Time Hypothesis may appear to be a fascinating theory, it lacks substantial evidence and is generally considered to be a product of conspiracy thinking. The calendar reform, which led to the deletion of 11 days in September 1752, was a legitimate adjustment that has since been acknowledged as a necessary step in ensuring that our understanding of time remains accurate. The historical timeline, as we know it, is supported by centuries of documentation, scientific research, and evidence from across the globe.

So, to those who continue to speculate and entertain these theories, it’s important to remember that history, as recorded, is based on the best available evidence, and while there may always be some mysteries to uncover, the facts as we understand them today are firmly grounded in reality.

About the Creator

QuirkTales

Welcome to QuirkTales, where the strange meets the intriguing! Dive into a world of peculiar stories, mind-bending mysteries, and the unexpected. Follow us for tales that spark curiosity and keep you coming back for more!

#QuirkTales

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.