The reason behind the early 2020s methane increase

Future Methane Emission Trends

Although methane levels have been rising for some time, the early 2020s were particularly noteworthy. According to a recent study, levels surged abnormally quickly for a quite annoying reason. According to the research, the atmosphere's ability to remove methane temporarily deteriorated while nature was producing more of it.

Consider it analogous to a bathtub. Yes, you can turn up the tap to overflow it. However, if the drain becomes partially clogged, you can also overflow it. The increase in the early 2020s, according to the experts, was a "tap + clogged drain" moment.

A decline in the use of chemical cleaners

Methane doesn't simply linger in the atmosphere. A large portion of it is destroyed by hydroxyl radicals, or OH, which react with methane and many other gases to help remove them from the atmosphere. They function as the atmosphere's detergent.

The researchers discovered signs of a significant decline in OH between 2020 and 2021. And that is very important. According to the scientists, the OH decline accounts for about 80% of the fluctuation in the rate of methane accumulation over this time period from year to year.

In other words, methane accumulated more quickly primarily due to a temporary decline in the atmosphere's cleaning ability.

Changes in COVID-19 air pollution

Why would OH drop, then? According to the study, there were changes in air pollution during the pandemic, particularly in nitrogen oxides (NOₓ).

The chemistry involved in the production and maintenance of OH is closely linked to NOₓ. OH levels probably decreased along with the decline in NOₓ emissions during lockdowns in many locations, which made it simpler for methane to persist.

The fact that lowering one pollutant might inadvertently alter the balance of other reactions is a good illustration of how chaotic atmospheric chemistry can be. Cutting NOₓ is crucial for both air quality and human health, therefore that doesn't mean it was "bad." However, it does indicate that the climate system may react in complex ways.

The methane tap was turned up by nature.

The "tap" was also appearing as the "drain" weakened. A prolonged La Niña episode (2020–2023) in the early 2020s delivered wetter-than-normal conditions to much of the tropics.

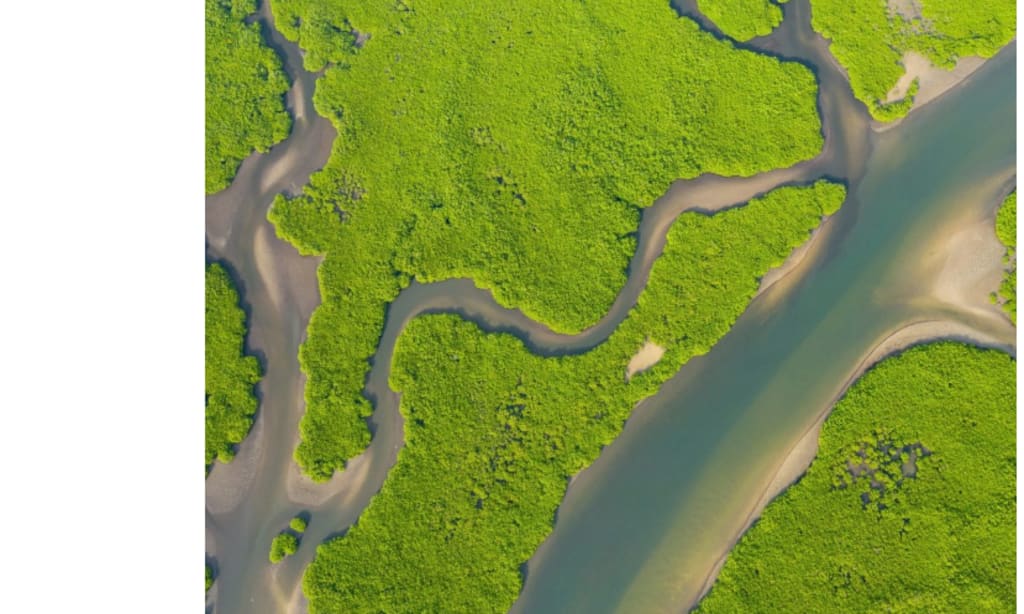

Because microorganisms frequently produce methane in damp, low-oxygen settings, weather conditions are important. Warm, rainy conditions turn some inland rivers, saturated soils, and flooded marshes into methane factories.

According to the study, these factors increased methane generation in regions such as Southeast Asia and tropical Africa. Additionally, it notes increases in lakes and wetlands in the Arctic, where warmth enhances microbial activity.

Furthermore, the sensitivity is reciprocal: the researchers point out that during a severe drought caused by El Niño in 2023, methane emissions from South American wetlands decreased. This serves as a reminder that methane levels can fluctuate significantly in response to climate extremes.

The study found that between 2019 and 2023, atmospheric methane increased by almost 55 parts per billion, peaking at 1921 ppb in 2023.

In 2021, the pace reached a peak of about 18 ppb in a single year, which the authors characterise as an 84% increase over the growth rate in 2019.

The function of microbiological sources

Many people will be surprised to learn that the researchers did not attribute the early-2020s jump mostly to emissions from fossil fuels or smoke from wildfires.

They cite isotopic data, or chemical fingerprints in methane, which indicates the change was dominated by microbiological origins. Here, "microbial sources" refers to agriculture, such as paddy rice, inland waters (lakes, rivers, and reservoirs), and wetlands.

These sources are particularly crucial in a world that is becoming warmer and more unpredictable because of their rapid response to temperature and precipitation.

A significant modelling issue

Another unsettling conclusion is that many popular "bottom-up" models—those that base emissions estimates on ecosystems and processes—might not adequately represent flooded systems, particularly inland waters and their rapid change.

According to the study, inland lakes and wetlands are under-represented in many global methane models, and their emissions can fluctuate more than previously thought. If so, it complicates climate planning as you can't effectively control what you can't measure.

Implications for reducing methane

"Give up" or "policy doesn't matter" are not statements made by the study. One of the quickest methods to reduce warming in the short term is still to stop methane leaks from petrol and oil.

However, the report cautions that methane targets cannot ignore climate-driven emissions in favour of concentrating solely on human-controlled emissions.

"Methane emissions from wetlands, inland waters, and paddy rice systems will increasingly shape near-term climate change as the planet gets warmer and wetter," Boston College study co-author Hanqin Tian stated.

"If the Global Methane Pledge is to meet its mitigation goals, it must take into consideration both anthropogenic controls and climate-driven methane sources."

Future Methane Emission Trends

By offering the most recent global methane budget through 2023, the study explains why atmospheric methane increased so quickly, according to Philippe Ciais, lead author from the University of Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines.

It also demonstrates that future trends in methane will be influenced by climate-driven changes in both natural and managed methane sources, in addition to emission limits.

The spark from the early 1920s demonstrates how quickly methane may increase when microbial emissions are increased by climate circumstances and the atmosphere's chemistry momentarily ceases to effectively scrub methane.

The neat narratives we like to tell, in which emissions are solely attributable to human activity and policy changes neatly map onto the atmosphere, may be overpowered by that combination.

Weather patterns, wetlands, inland waters, agriculture, and the chemistry of the air itself are all intertwined with methane in the real world. "Alive" methane is becoming a bigger climatic issue as the earth heats and rainfall fluctuates between floods and droughts.

Unless we improve our ability to monitor the aquatic regions of the Earth that silently make changes, methane will change more quickly and in unpredictable ways.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.