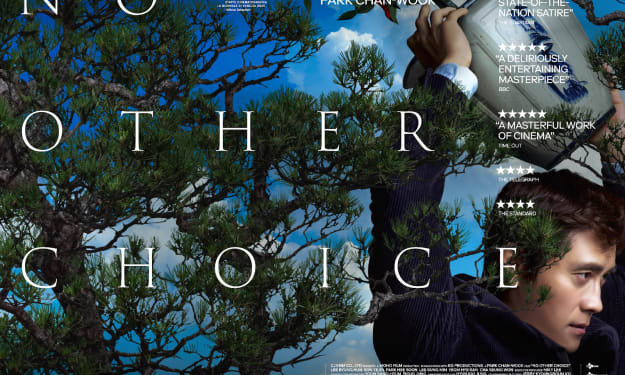

In Defense of Hamnet: Why Emotional Truth Matters More Than Historical Permission

A defense of one of the best movies of 2025.

When Sir Ian McKellen recently dismissed Hamnet as “improbable,” suggesting that Shakespeare’s imagination “certainly didn’t just come from family life,” he was not merely critiquing a film. He was, perhaps unintentionally, applying the wrong standard to the kind of story Hamnet is trying to tell.

And that distinction — between historical truth and emotional truth — is where the entire debate actually lives.

McKellen’s criticism is understandable. He has spent a lifetime immersed in Shakespeare, in scholarship, in performance, in a tradition that treats the Bard’s work with near-sacred reverence. But reverence can become a form of gatekeeping when it insists that only one framework — the historical, the academic, the provable — is legitimate.

Hamnet is not working in that framework. It never claims to.

It is working in the tradition of poetic truth — a tradition that predates Shakespeare by nearly two thousand years.

Aristotle Already Solved This Argument

Long before Shakespeare ever picked up a pen, Aristotle made a crucial distinction in Poetics:

History tells us what did happen.

Poetry tells us what could happen — what feels universally true.

This is not a minor footnote. It is the philosophical foundation of narrative art.

By Aristotle’s definition, poetry (and by extension, cinema) is not inferior to history — it is broader. It does not claim factual accuracy. It claims human accuracy. It seeks not documentation, but resonance.

When Hamnet imagines the emotional aftershocks of a child’s death within Shakespeare’s marriage, it is not claiming causation. It is exploring possibility. It is asking: What might grief look like inside this family?

Not: What literally happened?

To demand that the film meet historical standards is to commit a category error. It is like criticizing a painting for not being a photograph.

The Plumber, the Paycheck, and Emotional Causality

A plumber is not a plumber because he is spiritually moved by pipes.

He is a plumber because he is paid to be one.

But why does he want the paycheck?

Maybe he wants stability.

Maybe he wants to support his family.

Maybe he wants to give his children a better life than he had.

There is no direct link between plumbing and love — yet the emotional motivation is still real. The job is not inspired by family in a literal sense, but in a human one.

That is emotional causality.

Shakespeare did not “write Hamlet because his son died.”

But grief, love, distance, guilt, and loss may still have shaped the emotional weather of his inner life.

To say that those experiences could not have mattered is far more presumptuous than suggesting they might have.

What Hamnet Is Actually Saying

McKellen also questioned the idea that Anne Hathaway (as portrayed in the film) did not understand what a play was or had never seen one. But this misreads the scene.

Anne is not overwhelmed because she is ignorant of theatre.

She is overwhelmed because she is seeing her husband’s grief — publicly, vulnerably, shared with strangers — when he had not shared it with her.

She realizes that the part of himself he withheld from her has been given to the world.

That is the source of her emotion.

This is not historical speculation.

It is emotional logic.

And it is supported, beautifully, by the silent communication between Paul Mescal and Jessie Buckley in the film’s final moments. Their shared looks do what language cannot. They show two people finally understanding each other through the strange translation of art.

Shakespeare the Human, Not the Marble Statue

We are often told that Shakespeare may not have been a good husband. That he may not have been kind. That he may not have been present.

All of that may be true.

But being flawed does not mean being unfeeling.

Being distant does not mean being untouched.

Being complicated does not mean being hollow.

Hamnet does not sanitize Shakespeare. It humanizes him.

And that is the film’s quiet power: it reminds us that even legends were once people who loved, failed, and lost.

Why This Criticism Feels Misplaced

The complaints about Hamnet do not read like responses to the film itself. They read like objections to its right to exist — as if emotional storytelling needs permission from scholarship.

But art does not ask permission.

It asks recognition.

And Hamnet recognizes something deeply human:

that love and grief do not need footnotes to be real.

It is not a claim about where Shakespeare’s imagination came from.

It is a meditation on where all imagination comes from.

From being alive.

About the Creator

Sean Patrick

Hello, my name is Sean Patrick He/Him, and I am a film critic and podcast host for the I Hate Critics Movie Review Podcast I am a voting member of the Critics Choice Association, the group behind the annual Critics Choice Awards.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.