When the Postman Rang Twice: How Two Hollywood Eras Told the Same Story Differently

The 1946 and 1981 versions of The Postman Always Rings Twice reveal how much Hollywood—and America—changed in 35 years.

Two Versions, One Dangerous Obsession

When a story is strong enough, Hollywood will find a way to tell it again. Few tales prove that better than The Postman Always Rings Twice, James M. Cain’s 1934 novel of lust, greed, and guilt.

The book has been filmed several times, but two American versions—Tay Garnett’s The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946) and Bob Rafelson’s remake in 1981—stand as striking reflections of their times. Each tells the same story of a drifter and a married woman who fall into an affair and a murder plot. Yet each film feels born from an entirely different moral universe.

The 1946 movie is a model of postwar restraint, shaped by the Production Code and the moral anxieties of the 1940s. The 1981 version is earthy, psychological, and unfiltered, emerging from a Hollywood free of the old rules. One suggests danger; the other immerses us in it.

Hollywood in Black and White (1946)

When MGM released The Postman Always Rings Twice in 1946, America was still adjusting to peace after World War II. Moviegoers were drawn to stories that channeled uncertainty and temptation—key ingredients of film noir.

Director Tay Garnett used that mood brilliantly. The film’s visual style—deep shadows, glowing light, and narrow spaces—mirrored the story’s moral traps. Lana Turner’s Cora, dressed almost entirely in white, embodied a perfect contradiction: purity masking corruption. Opposite her, John Garfield played Frank as a restless drifter pulled into a fate he can’t escape.

Because the Hays Code forbade explicit depictions of crime or passion, Garnett’s version depends on suggestion. The camera lingers on glances, pauses, and tension rather than physicality. What could not be shown was implied, and that tension gave the movie its power.

The result is one of the great noir dramas of its time—tight, stylish, and suffused with fatalism. MGM’s polish smooths the rougher edges of Cain’s novel, but the story’s darkness remains intact. Critics praised its intensity and its visual beauty. Audiences responded, too: the film grossed about $5 million on a $1.6 million budget, a solid hit for the studio.

The Heat of the Early Eighties (1981)

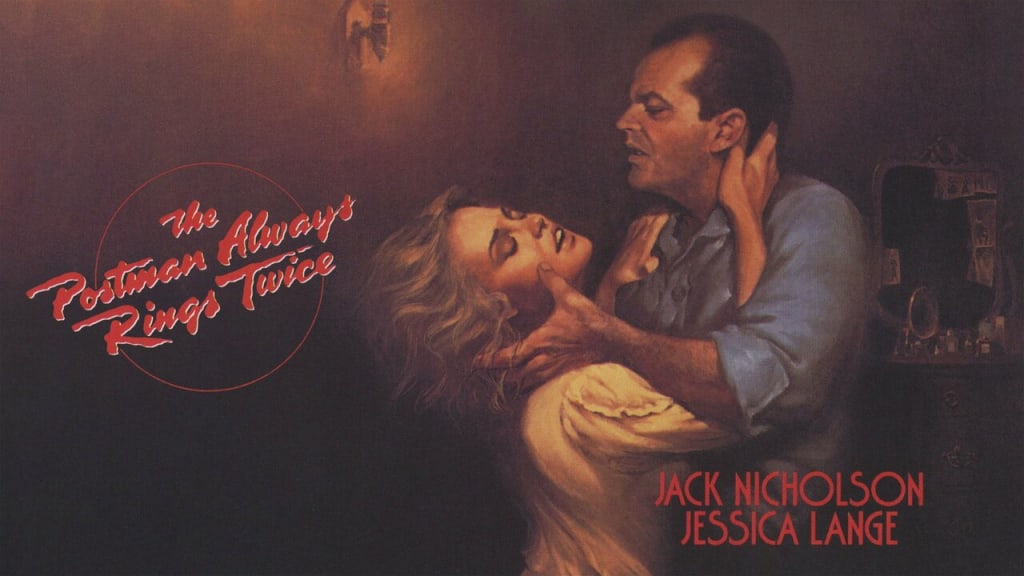

Three decades later, director Bob Rafelson—fresh off Five Easy Pieces and The King of Marvin Gardens—reimagined The Postman Always Rings Twice for a new generation. With Jack Nicholson and Jessica Lange leading the cast, and a screenplay by a young David Mamet, the 1981 version traded in noir stylization for raw realism.

Rafelson’s film was photographed by Sven Nykvist, Ingmar Bergman’s longtime cinematographer. His approach replaced Hollywood gloss with natural light and open space. Instead of studio sets, the story unfolds in sun-bleached diners, dusty roads, and cramped kitchens. The atmosphere feels lived-in, not manufactured.

Where Garnett’s film dealt in innuendo, Rafelson’s speaks plainly. It focuses on human emotion—the loneliness, frustration, and impulsiveness that drive Frank and Cora toward ruin. Their relationship is messy and volatile, stripped of glamour.

That realism didn’t land the same way for everyone. Critics admired the performances and cinematography but were divided on the film’s tone. Some found it beautifully crafted but emotionally distant. Others praised it for restoring the grit that censorship once erased.

Financially, the 1981 version was modestly successful. Made for around $12 million, it earned roughly $12.4 million in the U.S. and considerably more overseas, where its reputation was stronger. Still, it couldn’t match the enduring legacy of its predecessor.

A Mirror of Two Americas

The distance between these two Postmans says as much about the evolution of American film as it does about the story itself.

In 1946, Hollywood was built on moral control. The studio system dictated not only who made movies but what could be shown. Even crime dramas had to deliver moral clarity: sin could be thrilling, but it had to be punished. Garnett’s film ends in tragedy because that was the only way to make the story acceptable.

By 1981, that world was gone. The Production Code had collapsed in the late 1960s, and the auteur era had taught audiences to accept ambiguity. Rafelson’s remake arrived in a Hollywood where directors and stars had more freedom to explore desire, consequence, and moral gray areas without apology.

Each version reflects its America—the 1940s film a product of repression and recovery, the 1981 film a product of disillusionment and self-exploration. One hides its passion behind smoke and silk; the other confronts it directly.

When the Postman Rings

Both films end the same way: with fate closing in, as if destiny itself has knocked twice. But their meanings diverge.

The 1946 film warns us about moral temptation. The 1981 film warns us about human isolation. One delivers judgment; the other, observation.

That’s the lasting fascination of The Postman Always Rings Twice. It isn’t just a story of crime—it’s a story about what each generation believes sin should look like. When the postman rings, it’s not only the door he’s calling on. It’s the conscience of the time.

About the Creator

Movies of the 80s

We love the 1980s. Everything on this page is all about movies of the 1980s. Starting in 1980 and working our way the decade, we are preserving the stories and movies of the greatest decade, the 80s. https://www.youtube.com/@Moviesofthe80s

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.