What You Call ‘Deaf Anger,’ I Call ‘Access Fatigue’

From the sting of "never mind" to the burden of tone policing: Why I’m done prioritizing your comfort over my right to exist.

Image description: Black background with an outstretched hand reaching up and several hands grabbing it's wrist

The Silence You Don’t See

They tell us that silence is golden, but for a Deaf or DeafBlind person, silence is often something forced upon us. It isn’t the absence of sound; it’s the presence of a barrier.

We spend our lives navigating a world that wasn’t built for us, acting as our own advocates, our own technicians, and our own educators. We are expected to do this with a smile, a infinite well of patience, and a "grateful" attitude toward any crumb of accessibility tossed our way. But what happens when the patience runs out? What happens when the "never minds" and the "we don't have the budget" excuses finally hit a wall?

What the hearing world sees as "Deaf Anger" is rarely about a single moment. It is the visible smoke from a fire that has been smoldering for years. It is the byproduct of Access Fatigue—the exhaustion of being told that your right to understand the world is a "special request" rather than a human right.

If you’ve ever wondered why the Deaf person in your life seems "sharp," "abrupt," or "difficult," it’s time to stop looking at their reaction and start looking at the environment that triggered it.

It’s time to talk about the emotional labor of existing in a world that asks us to stay quiet so that you can stay comfortable.

The Survival Mask: Why We Stay Silent

To understand Deaf anger, you first have to understand the Deaf Silence. Many of us have spent years mastering the art of the "pleasant nod." We do this not because we are satisfied, but because we are afraid.

- The Risk of "Difficult": In the professional world, a Deaf person who demands their legal rights is often labeled "difficult" or "not a team player." Once that label sticks, the interpreters get harder to book, the promotions stop coming, and the "budget" for your access mysteriously dries up.

- The Service Ransom: When you rely on an agency or an individual for interpreting, there is an unspoken power dynamic. If you express frustration at their incompetence, you risk losing the service altogether. We suppress our anger as a form of insurance.

- Cultural Gaslighting: We are often told that our directness—a natural part of ASL culture—is "rude" by hearing standards. We are forced to filter our natural expressions through a "hearing-friendly" lens, which is like being forced to speak in a whisper when you want to scream.

- The Isolation Threat: We constantly calculate: Is my dignity worth my inclusion? If we speak up, we risk being labeled "too much work." We often swallow our frustration because we know that if we make hearing people feel guilty, they will simply stop inviting us to the table.

The survival mask isn't a choice; it's a silent ransom we pay just to keep our seat at the table.

The Anatomy of Access Fatigue

Access Fatigue isn't just being tired; it’s a physiological burnout. It’s the result of:

- Hyper-Vigilance: Constantly scanning the room to see who is talking, what the mood is, and what you’re missing.

- The Translation Gap: The 2-second delay between the world happening and you receiving the information, which leaves you perpetually "behind" the joke or the instruction.

- The Advocacy Tax: Having to explain how to include you to the very people who are supposed to be including you.

- The Physicality of Focus: The raw body exhaustion from the intense, constant concentration required to "listen" without sound.

Access fatigue isn’t just 'being tired'—it is the cumulative weight of working twice as hard for half the inclusion.

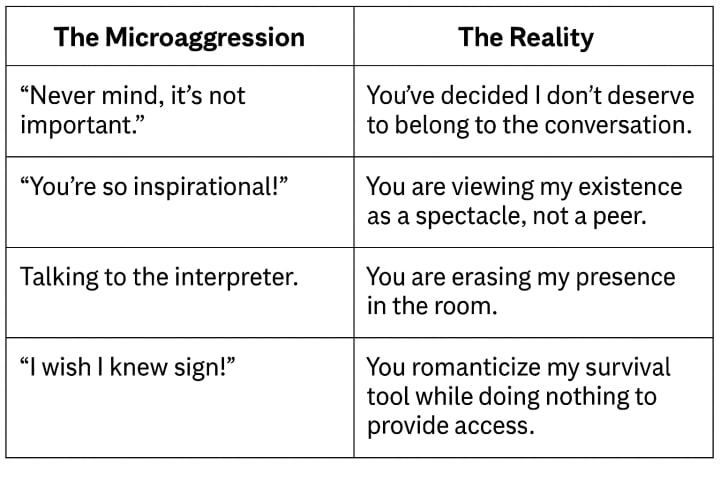

The Microaggression Matrix

Image Description of the Microaggression Matrix:

Phrase: “Never mind, it’s not important.” — The Reality: You’ve decided I don’t deserve to belong.

Phrase: “You’re so inspirational!” — The Reality: You view my existence as a spectacle.

Phrase: Talking to the interpreter. — The Reality: You are erasing my presence.

Phrase: “I wish I knew sign!” — The Reality: You romanticize my survival tool.

Systemic Gaslighting: "It’s Not in the Budget"

The most common phrase used to suppress our anger is, "We just don't have the budget for an interpreter/captions/access need"

This is gaslighting. What they are actually saying is: "Your presence is not worth the cost." When we get angry at this, we are told to be "reasonable." But there is nothing reasonable about being excluded from a workplace, a classroom, or a doctor’s appointment.

Our anger isn't a personality flaw; it is a protest against a world that treats our human rights as an optional line item.

Impact Over Intent: The Cost of Your Comfort

To the hearing friends, colleagues, and "allies" reading this: your "good intentions" are not a substitute for actual access. Intent is about how you feel; impact is about whether or not I can participate in my own life.

- The Comfort Trap: When you ask us to "be patient" or "calm down," you are asking us to prioritize your comfort over our exclusion. You are essentially saying that our response to being marginalized is more offensive than the marginalization itself.

- The Myth of "Trying Your Best": "Trying" to find an interpreter or "trying" to remember to face us when you speak doesn't provide access. If the result is that we are still left out, the effort—while noted—has failed. We cannot live our lives on the "effort" of others; we need results.

- Tone-Policing as a Silencing Tool: If a Deaf person is angry, don't use that anger as an excuse to stop listening. Our "tone" is often the only thing loud enough to break through the layers of systemic indifference.

The shift is simple: Stop asking if your heart was in the right place, and start asking if the door was actually open.

Conclusion: A Message to the Exhausted

To my fellow Deaf and DeafBlind community: You are not "unmotivated" or "mean." You are navigating a world that wasn't built for you while carrying the weight of everyone else's comfort. Your anger is valid. Your fatigue is real.

And to the hearing world: The next time you see "Deaf Anger," don't ask us to calm down. Ask yourself why you were so comfortable with our silence in the first place.

My anger is not a threat. It is a sign of self-respect. It means I still believe I deserve to be heard, even when the world is trying to hold my hands down.

The Next Time You’re in the Room...

Don’t just "sympathize" with this article—audit your own spaces. Look at your next meeting, your social gathering, or your digital content. If a Deaf or DeafBlind person isn't there, or if they are there but struggling to keep up, ask yourself: "What barrier am I allowing to exist?" Stop waiting for us to ask for a seat. Start making sure the chair is already at the table.

About the Creator

Tracy Stine

Freelance Writer. ASL Teacher. Disability Advocate. Deafblind. Snarky.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.