It is a small word.

Four letters. One syllable. Easy to say. Easy to dismiss. Easy to hide inside.

Just.

On its own, it sounds harmless. It sounds soft. It sounds like reassurance. It sounds like comfort.

In reality, it erases.

Living with chronic illness means becoming familiar with the word in ways most people never notice. It appears in conversations, in advice, in casual remarks that are meant to simplify something that cannot be simplified.

Just rest.

Just pins and needles.

Just the shakes.

Just a bit tired.

Just exercise more.

Just lose weight.

Just change your diet.

Just push through it.

Each use of the word carries the same quiet implication: what you are experiencing is smaller than you believe it to be.

The word does not acknowledge complexity. It reduces it.

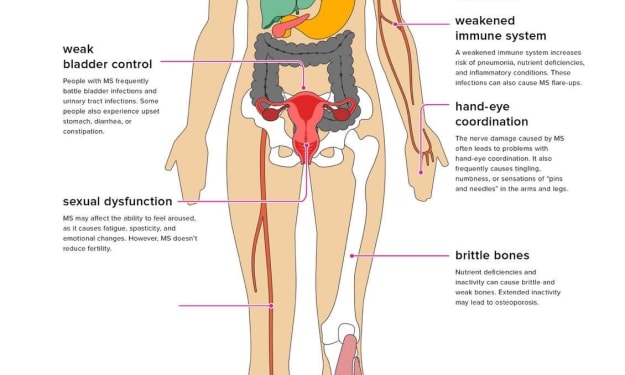

Multiple sclerosis, like many invisible illnesses, does not present itself neatly. Symptoms fluctuate. Fatigue arrives unpredictably. Sensations appear without warning. The nervous system misfires in ways that cannot always be explained or controlled.

When someone describes neurological fatigue as something to “just rest” away, they reveal a fundamental misunderstanding. Rest does not always resolve neurological fatigue. Rest does not repair damaged myelin. Rest does not restore interrupted nerve signals.

Rest helps. Rest protects. Rest maintains. Rest does not cure.

Describing symptoms as “just pins and needles” reduces neurological disruption to a minor inconvenience. Pins and needles in the context of MS are not the temporary sensation experienced after sitting awkwardly. They are evidence of interrupted communication between brain and body.

Describing tremors as “just the shakes” dismisses the loss of physical control. Describing exhaustion as “just tiredness” dismisses the reality of neurological depletion.

The word removes seriousness. It removes legitimacy.

Ableism often hides inside language that appears harmless. The word “just” allows people to offer explanations without engaging in understanding. It protects the speaker from discomfort. It places the burden of adjustment back onto the disabled person.

Just exercise more.

Just eat differently.

Just try harder.

These statements assume control where control does not exist. They assume responsibility where responsibility is irrelevant. They suggest that disability is something that can be corrected through effort, discipline, or lifestyle.

This narrative is comforting for people who have never experienced chronic illness. It preserves the belief that the body is fully controllable. It protects the illusion that health is guaranteed through the right choices.

Chronic illness disrupts that illusion.

Multiple sclerosis is not caused by a lack of exercise. It is not caused by weight. It is not caused by insufficient effort. It is a neurological condition shaped by immune dysfunction, not personal failure.

The word “just” shifts the focus away from medical reality and toward personal responsibility. It subtly suggests that disability exists because of something the disabled person did or failed to do.

This suggestion creates shame.

Shame for resting.

Shame for needing support.

Shame for existing in a body that does not meet expectation.

The harm of the word extends beyond conversation. It influences self-perception. Hearing your experience reduced repeatedly teaches you to question yourself. It encourages minimisation. It encourages silence.

You begin to wonder whether your symptoms are serious enough to acknowledge. You begin to hesitate before asking for help. You begin to internalise the idea that your suffering must be measured against someone else’s comfort.

Language shapes reality.

The difference between “fatigue” and “just tired” is the difference between recognition and dismissal. The difference between “neurological symptoms” and “just pins and needles” is the difference between legitimacy and doubt.

The word exists to make disability more comfortable for people who do not live with it.

It shrinks something that is already difficult to carry.

Chronic illness does not need to be softened to make it acceptable. It needs to be understood.

There is nothing “just” about living in a body that cannot be relied upon. There is nothing “just” about losing predictability. There is nothing “just” about learning to navigate the world differently than expected.

Disabled people do not need simplification. They need recognition.

They need language that acknowledges reality rather than diminishing it.

They need space to exist without being reduced.

The word may seem small. Its impact is not.

“Just? What a horrible candle-snuffing word – it’s like saying he’s just a dog.” ~ JM Barrie

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.