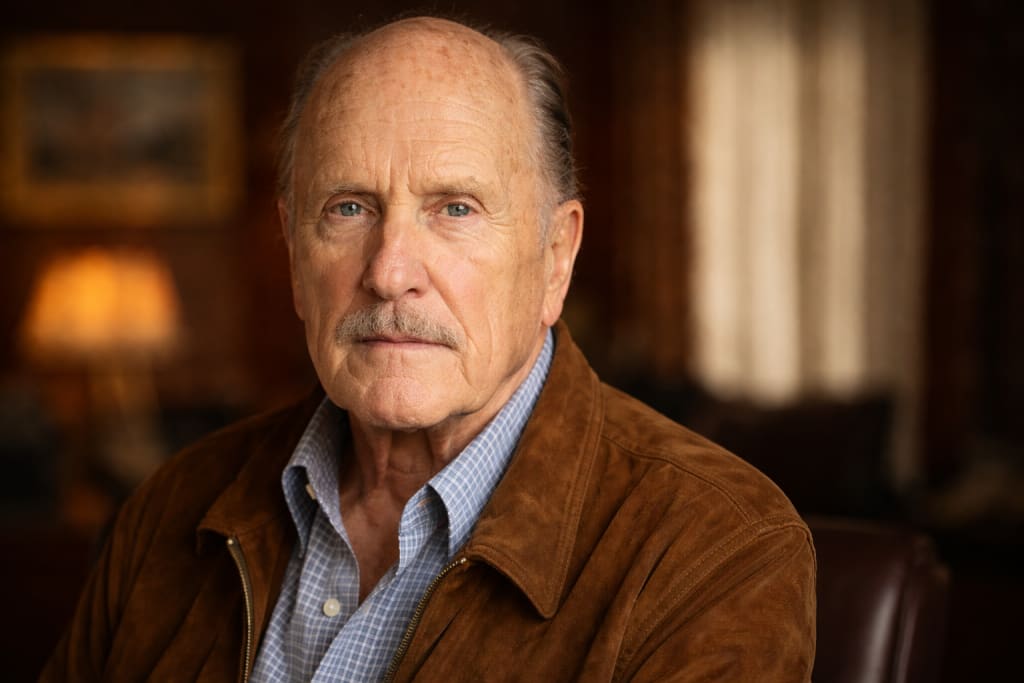

Robert Duvall

Craft, Contradiction, and the Making of an American Actor

Robert Duvall has one of those faces you remember even when you forget the movie. He can walk into a scene, say a single line, and suddenly the whole story feels more grounded. For more than six decades, he’s been part of the American film landscape, often not as the loudest presence in the room, but as the one you believe instantly.

He’s not a celebrity in the modern, publicity-driven sense. He’s a working actor, in the old-fashioned, almost stubborn meaning of the term. And that’s what makes him worth examining: not just as a collection of famous roles, but as a case study in how a serious actor builds a career, chooses material, and protects his craft over time.

This isn’t a fan biography. It’s a look at what Robert Duvall represents: discipline over flash, character over vanity, and the long, often unglamorous path of a career that outlives trends.

Early Life and Late Start: The Unlikely Beginning

Robert Duvall was born in 1931 in San Diego, California, the son of a U.S. Navy rear admiral and a mother with Midwest roots and some distant connection to American history. The military background mattered. Growing up with a strict, achievement-based family culture shapes how you approach work, and in Duvall’s case, that seriousness is hard to miss. Even when he’s playing a drunk attorney or a gentle country preacher, there’s a certain discipline underneath.

Unlike many modern actors who start as child stars or social media personalities, Duvall didn’t emerge from a factory system. He studied drama at Principia College in Illinois, served in the Army during the Korean War (though he never saw combat), then moved to New York to study acting under Sanford Meisner at the Neighborhood Playhouse.

The Meisner Influence: Listening as a Superpower

You see the Meisner training in Duvall’s work immediately if you know what to look for. Meisner’s approach centers on behavior and truthful reaction: “acting is living truthfully under imaginary circumstances.”

Duvall is a case study in this method. He rarely looks like he’s “performing.” Instead, he responds. Watch him in a scene and you’ll notice how much he’s actually listening to the other actors. His eyes move in ways that aren’t pre-planned. He waits, he reacts, he shifts, he adjusts. The performance feels alive because it is.

In the early New York years, he shared rooms and stages with future legends—Dustin Hoffman, Gene Hackman, others who also spent years doing off-Broadway and odd jobs while waiting for something to break. That long apprenticeship is crucial. Many actors today jump from bit parts directly into leading roles before they’ve fully built their craft. Duvall spent a decade learning, failing, auditioning, and building muscle.

The Breakthrough: “To Kill a Mockingbird” and the Power of Silence

Duvall’s first major film role was Boo Radley in *To Kill a Mockingbird* (1962). It’s almost funny in hindsight: one of the most expressive actors of his generation becomes famous playing a character who barely speaks.

Boo Radley appears at the edges of the story, a mix of myth and rumor, until he physically steps into the frame at the end. When he does, Duvall doesn’t oversell the moment. He doesn’t play Boo as a horror figure or a tragic saint. He just seems… damaged, shy, and deeply human.

That performance set a tone for his career: he could come in late, say little, and change the emotional temperature of a film. It’s a skill that doesn’t draw immediate attention, but directors notice it, and they remember.

The 1970s: Duvall in the Center of the New Hollywood Storm

The 1970s were a golden era for American cinema, often called “New Hollywood,” where directors like Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, and others reshaped studio filmmaking. Duvall was in the thick of it.

Tom Hagen in “The Godfather”: Authority Without Volume

Tom Hagen in *The Godfather* (1972) is one of Duvall’s signature roles. He plays the Corleone family’s adopted son and lawyer—a character with almost no wasted motion. Hagen is smart, loyal, and emotionally contained, the quiet opposite of Sonny’s temper and Michael’s slow-burning transformation.

What’s striking about Duvall’s performance is the restraint. In a movie filled with iconic scenes, he never grandstands. He steadies the film. In the scene where he informs a Hollywood producer that the Corleone family will not be refused, Duvall plays it with incredible calm. No raised voice, no melodrama. Yet you feel the threat.

Duvall was nominated for an Oscar for *The Godfather Part II* (1974) and was actually offered a bigger salary for Part III, but he walked away when the pay difference between him and Al Pacino became too large. That decision tells you something about his relationship to the industry: he cares about the work, but he also cares about not being treated as an afterthought.

“Apocalypse Now”: The Line That Wouldn’t Die

Then there’s *Apocalypse Now* (1979) and Lieutenant Colonel Bill Kilgore—the surfing-obsessed war officer who speaks one of the most quoted lines in film history: “I love the smell of napalm in the morning.”

Kilgore could easily have been a cartoon: a one-note satire of American military arrogance. Duvall makes him disturbingly likable. You laugh at his eccentricities, then slowly realize how insane this behavior is in the context of war.

That tension—between charm and horror—is what sticks with you. Duvall doesn’t wink at the audience. He plays Kilgore as a man utterly at ease with what he’s doing. It’s that lack of self-awareness that makes the character chilling.

The trade-off, of course, is that the iconic line has often overshadowed the nuance of the role. People remember the quote, not the quiet moments—like the way Kilgore’s expression changes when he hears that one of the soldiers is a famous surfer. Those little choices are where the craft lives.

Character Actor or Leading Man? Duvall Refuses the Categories

Many discussions about Duvall get hung up on labels: Is he a character actor or a leading man? The answer is that he’s both, and neither. He does what the role and the story require.

In the 1970s and 1980s, he alternated between supporting roles in major films and leading roles in smaller, more personal projects. That balance wasn’t accidental. It’s a smart way to survive in an industry that often wants to push actors into a narrow type.

“The Great Santini”: Toxic Masculinity Before It Became a Buzzword

In *The Great Santini* (1979), Duvall plays Marine pilot Bull Meechum, a tyrannical father who treats his family like a squadron. The role earned him an Oscar nomination for Best Actor and remains one of his most emotionally raw performances.

Meechum isn’t a villain in a simple sense. He’s a product of his training, his era, and his ego. Duvall plays both the cruelty and the vulnerability: the man who humiliates his son on the basketball court and the same man who is strangely lost when he’s not in uniform or not in control.

The film wasn’t a massive commercial hit, but it showed something crucial: Duvall could carry a movie emotionally, not just support it. It’s the kind of role many actors avoid because it requires them to show the worst sides of masculinity without sugarcoating or distancing themselves.

The Quiet Masterpiece: “Tender Mercies” and the Art of Understatement

If you want to understand Robert Duvall at his purest, *Tender Mercies* (1983) is where to look. He plays Mac Sledge, a washed-up country singer trying to rebuild his life in rural Texas, working at a roadside motel and slowly forming a relationship with a widow and her young son.

Duvall reportedly insisted on doing his own singing and even co-wrote some of the songs. They’re not polished Nashville hits; they feel like songs a tired man might hum at a kitchen table. That’s exactly what makes them believable.

There are no big breakdown scenes or melodramatic speeches. The performance is quiet, observant, and patient. You see the weight of regret in how Mac moves, in how he talks about his past with a careful distance.

Duvall won the Academy Award for Best Actor for *Tender Mercies*, and it’s one of the rare times the Oscars rewarded subtlety over showmanship. For actors, the lesson here is clear: you don’t always need high volume to have high impact. But the trade-off is that roles like this can disappear from the public memory faster than a more flamboyant performance might.

Television and the Long Game: “Lonesome Dove” and Beyond

By the late 1980s, many film actors still saw television as a step down. Duvall didn’t approach it that way. When *Lonesome Dove* (1989), a TV miniseries based on Larry McMurtry’s novel, came along, he took it seriously—and his portrayal of retired Texas Ranger Augustus “Gus” McCrae became one of his most beloved roles.

Gus is charming, lazy in appearance but sharp in mind, and quietly brave. Duvall plays him with humor and melancholy, without leaning too hard on either. The performance showed that long-form television could give an actor room to develop a character gradually, in a way films sometimes can’t.

As TV evolved into what people call the “prestige era,” Duvall’s work in ,Lonesome Dove, looks almost prophetic. It proved that an actor with serious film credentials could do television without losing status—and in some ways, could gain something: time.

Aging on Screen: Later-Career Roles and What They Reveal

Many actors struggle with aging on screen. They cling to younger roles, chase cosmetic fixes, or disappear entirely. Duvall did something else: he leaned into roles that matched his years and experience.

“The Apostle”: Faith, Flaws, and Full Creative Control

In *The Apostle* (1997), Duvall didn’t just act; he wrote, directed, and financed the film himself. He plays Sonny, a charismatic Pentecostal preacher who is both deeply religious and deeply flawed. After committing a violent act in a fit of rage, Sonny flees, renames himself, and starts a new church in a small town.

Religious characters in American film are often either smug hypocrites or pure saints. Duvall refuses both. Sonny is capable of genuine spiritual power and genuine moral failure. He’s manipulative and sincere at the same time.

Financing the film himself was a major risk. It took years to get made. Studios were not clamoring for a small, quiet story about a middle-aged preacher with a checkered past. But *The Apostle* stands as a personal statement: this is what Duvall wanted to explore when he had full control.

From a practical standpoint, that decision shows the trade-off of artistic independence: you gain freedom, but you also take on financial and career risk. Not many actors are willing to do that in their 60s.

“Get Low” and Quiet Autumn Roles

Later roles in films like *Get Low* (2009) continued this pattern. In that film, Duvall plays a reclusive man who wants to hold his own funeral while still alive, so he can listen to what people say. The premise sounds quirky, but Duvall plays it with gravity and regret, making the character feel like someone you might actually encounter in a small town if you stayed long enough.

Even in more commercial projects—*Open Range*, *The Judge*, *Secondhand Lions*—he tends to bring a grounded, lived-in quality. He doesn’t chase youth. He allows age to show in his posture, his voice, the way he moves. That honesty is rarer than it should be.

Style and Technique: What Sets Duvall Apart

Trying to pin down Robert Duvall’s “style” is tricky because he’s not an actor who calls attention to technique. Yet, if you watch enough of his work, patterns emerge.

Behavior Over Speech

Duvall uses dialogue economically. Many of his best moments are non-verbal: a shift in eye contact, a slight pause before answering, a long, quiet stare. He doesn’t fill silence just to fill it.

This matters because actors often get caught up in line readings. Duvall focuses on behavior. How does the character sit? How do they enter a room? How do they look at someone they don’t trust? Those details do as much storytelling as the script.

Authenticity and Regional Detail

Duvall has a particular affinity for Southern and rural American characters, though he’s played all types. He often spends time in the regions he’s portraying, listening to speech patterns and local rhythms. His accents aren’t showy. They don’t sound like an impression; they sound like someone who grew up there.

This approach carries risks. When actors dive into regional types, there’s always the danger of stereotype. Duvall occasionally walks close to that line with broad, big characters. But he typically grounds them with enough internal life and contradiction that they feel like individuals, not types.

Emotional Range Without Emotional Exhibition

Duvall can play rage, grief, tenderness, and indifference—but he rarely does so in a way that looks like “Capital-A Acting.” You don’t see him chasing Oscar clips. The emotion tends to leak out sideways, in a half-choked sentence or a moment where he looks away rather than at the person he’s talking to.

For actors watching his work, the practical lesson is this: you don’t have to show everything you’re feeling. Often, the most compelling choices are the ones you resist.

Limitations and Critiques: Where Duvall Doesn’t Quite Land

No actor is perfect, and treating Duvall as some flawless legend does him a disservice. There are legitimate critiques and limitations in his body of work.

Typecasting in Americana

Duvall has done a large number of roles rooted in American, particularly Southern, settings—lawmen, ranchers, preachers, small-town figures. He’s good at them, but it does mean his on-screen identity can feel geographically narrow. Some viewers see “Duvall” and immediately expect a certain kind of American male archetype: tough, laconic, emotionally reserved.

That’s partly the industry’s fault. Casting directors like to go with what works. But it also means his range outside of that space is less explored on screen, even if it exists on stage or in lesser-known work.

The Risk of Familiarity

Because Duvall is so consistent, there are roles where he almost feels too comfortable—where the performance is still strong, but you recognize familiar patterns. It’s not phoning it in; it’s more that he has certain reliable tools he knows how to use.

For younger actors, this is a cautionary point: once you find something that works, the temptation to repeat it is strong. Staying inventive requires deliberate effort.

Lessons from Duvall’s Career: What His Path Teaches

Looking at Duvall’s trajectory, there are some clear takeaways for anyone interested in acting or long-term creative work.

1. The Long Apprenticeship Pays Off

Duvall didn’t become a star overnight. He spent years doing theater, small parts, and odd jobs. That slower path gave him both technique and resilience. In a culture obsessed with instant success, his career is a reminder that a long preparation phase is not wasted time.

2. Versatility Within a Grounded Core

He’s played lawyers, soldiers, cowboys, preachers, fathers, drifters, and loners. What connects them isn’t the job title or costume; it’s a sense that the character has a life before the first scene and after the last. He rarely feels like someone who exists only for the plot.

3. Choose Integrity Over Visibility

Walking away from ,The Godfather Part III, over unequal pay, financing ,The Apostle, himself, doing TV when film was considered more prestigious—these are all decisions rooted in long-term values rather than short-term optics. That doesn’t mean everyone can afford to make those choices, but they show a consistent internal compass.

4. Age Honestly

Duvall never pretended to be younger than he is. He took older roles as they came, and allowed his appearance, voice, and physicality to change on screen. For a profession so obsessed with youth, that’s quietly radical.

Conclusion:

Robert Duvall and the Value of Staying Real

Robert Duvall’s career isn’t about spectacle. It’s about showing up, listening, and telling the truth about flawed people in complicated situations. He rarely feels like he’s trying to impress you. Instead, he seems to be trying to disappear into whoever he’s playing.

In an era where acting often gets noticed most when it’s loud, quirky, or meme-ready, Duvall’s work reminds you of a different standard: the measure of a performance is whether you believe the person, not whether you remember the line.

His legacy isn’t just a list of great films—though there are plenty. It’s a model of how to build a life in the arts without losing yourself: train seriously, choose carefully, accept aging, and hold your ground when it matters.

You might forget some of the movies he’s in. You almost never forget him.

About the Creator

abualyaanart

I write thoughtful, experience-driven stories about technology, digital life, and how modern tools quietly shape the way we think, work, and live.

I believe good technology should support life

Abualyaanart

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.