Why Albert Einstein Never Received a Nobel Prize for Relativity

Unpacking the Nobel Committee’s decision, scientific culture of the early 20th century, and why Einstein’s greatest theory wasn’t the one that won him the world’s most prestigious scientific award.

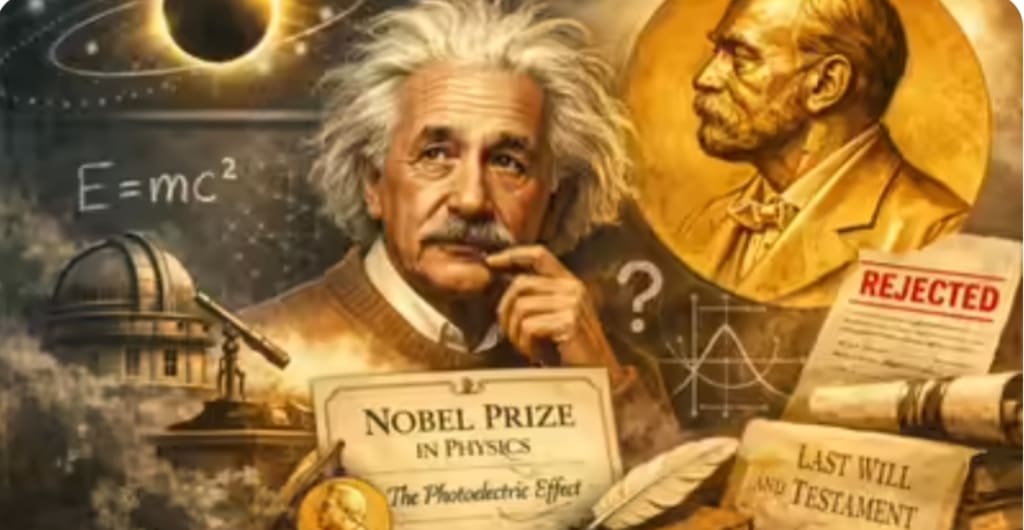

Albert Einstein — one of the most iconic scientists in history — forever changed our understanding of space, time, and gravity with his theory of relativity. Yet, when he finally won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921 (presented in 1922), it was not for relativity but for his explanation of the photoelectric effect. This is one of the most fascinating quirks in modern scientific history, revealing as much about scientific institutions as it does about Einstein’s genius.

---

The Triumph of a Revolutionary — But Not for His Most Famous Work

Einstein developed the special theory of relativity in 1905 and the general theory in 1915. These theories revolutionized physics by redefining concepts of space, time, and gravity, leading to predictions such as time dilation and the bending of light by massive objects. Yet, despite these breakthroughs, the Nobel Committee for Physics repeatedly declined to award him the prize for relativity. Instead, Einstein received the Nobel Prize “for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect.”

The photoelectric effect — which explains how light can eject electrons from a metal surface — was experimentally well‑supported and simple to verify. In contrast, relativity was abstruse, mathematically complex, and at that time not broadly accepted or fully confirmed by experimental data. This preference for clear empirical evidence over abstract theoretical work was central to the Nobel Committee’s decisions.

---

Experimental Proof Matters: Nobel Tradition and Relativity’s Proof

A key reason Einstein was not awarded the Nobel Prize for relativity was the Nobel Committee’s emphasis on experimental validation. Alfred Nobel’s will specifies that prizes are to be given to discoveries that confer “the greatest benefit to humankind” — a phrase interpreted at the time to mean discoveries that were solidly founded on observable, measurable phenomena.

Relativity’s predictions — especially those of general relativity — were difficult to verify in the early 1920s. Although Sir Arthur Eddington’s eclipse expedition in 1919 had measured the bending of starlight by the Sun, supporting Einstein’s prediction, some scientists still viewed the data as not entirely conclusive. The methods were complex, and some early critics even questioned whether the data justified the bold theoretical leap.

Because relativity was still seen by many as cutting‑edge and not yet fully proven, the Nobel Committee hesitated to award Einstein for it. Instead, they chose a contribution — the photoelectric effect — that had clear, reproducible evidence and immediate scientific impact.

---

Scientific Conservatism and Committee Skepticism

Another factor in the Nobel Committee’s decisions was the conservative nature of scientific institutions at the time. The Committee was dominated by members who valued work that could be experimentally tested and widely understood. The mathematical sophistication and conceptual novelty of relativity made many committee members uncomfortable or skeptical.

Notably, Allvar Gullstrand, a Swedish Nobel laureate and committee member, was a vocal skeptic of relativity. He reportedly argued that Einstein’s theory was not sufficiently useful or experimentally grounded to merit a Nobel Prize, advocating instead for work that yielded direct, measurable benefits. His influence significantly delayed Einstein’s recognition and led the committee to delay awarding a prize at all in 1921 rather than give it for relativity.

This internal divide reflected broader tensions in the scientific community: theorists championed bold conceptual frameworks, while experimentalists and more traditional scientists demanded solid proof before conferring the highest honors.

---

Political and Cultural Context

Although the scientific criteria were paramount, social and political undercurrents also played a role. Einstein’s prominence as a Jewish, pacifist scientist in the aftermath of World War I made him a controversial figure in some circles. Antisemitic and nationalist sentiments among certain academics likely heightened hesitancy toward honoring his most revolutionary work.

Many Nobel Committee members were aware that scientific consensus on relativity was still forming. Some may have feared that awarding relativity prematurely could diminish the prestige of the Nobel Prize if the theory were later contested or better understood.

---

The 1921 Prize and Its Unusual Citation

The Nobel Prize was not awarded in 1921 because the Committee could not agree on a suitable recipient. When two prizes became available in 1922, the Academy reached a compromise: award Einstein the delayed 1921 prize for his work on the photoelectric effect, which had clear experimental backing, while explicitly excluding relativity from consideration in the citation. This was a unique and pointedly cautious formulation.

Einstein’s Nobel diploma remains unusual because it essentially states what the award is not for — a testament to how controversial relativity was even at the height of Einstein’s fame.

---

Legacy: Relativity Vindicated and Nobel Decisions Revisited

In the decades after Einstein’s Nobel Prize, the predictions of relativity have been confirmed across countless experiments, from gravitational lensing to the recent detection of gravitational waves. The theory now stands as a cornerstone of modern physics.

Yet, the Nobel Committee has never retroactively awarded relativity its own Nobel Prize. This highlights a broader truth about scientific recognition: groundbreaking ideas may be validated long after initial skepticism, and institutions often reward certainty over groundbreaking but unproven insights.

Einstein’s Nobel Prize — for an achievement overshadowed by his own fame — reminds us that scientific progress and scientific honors don’t always align neatly. His legacy, however, needs no medal to endure.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.