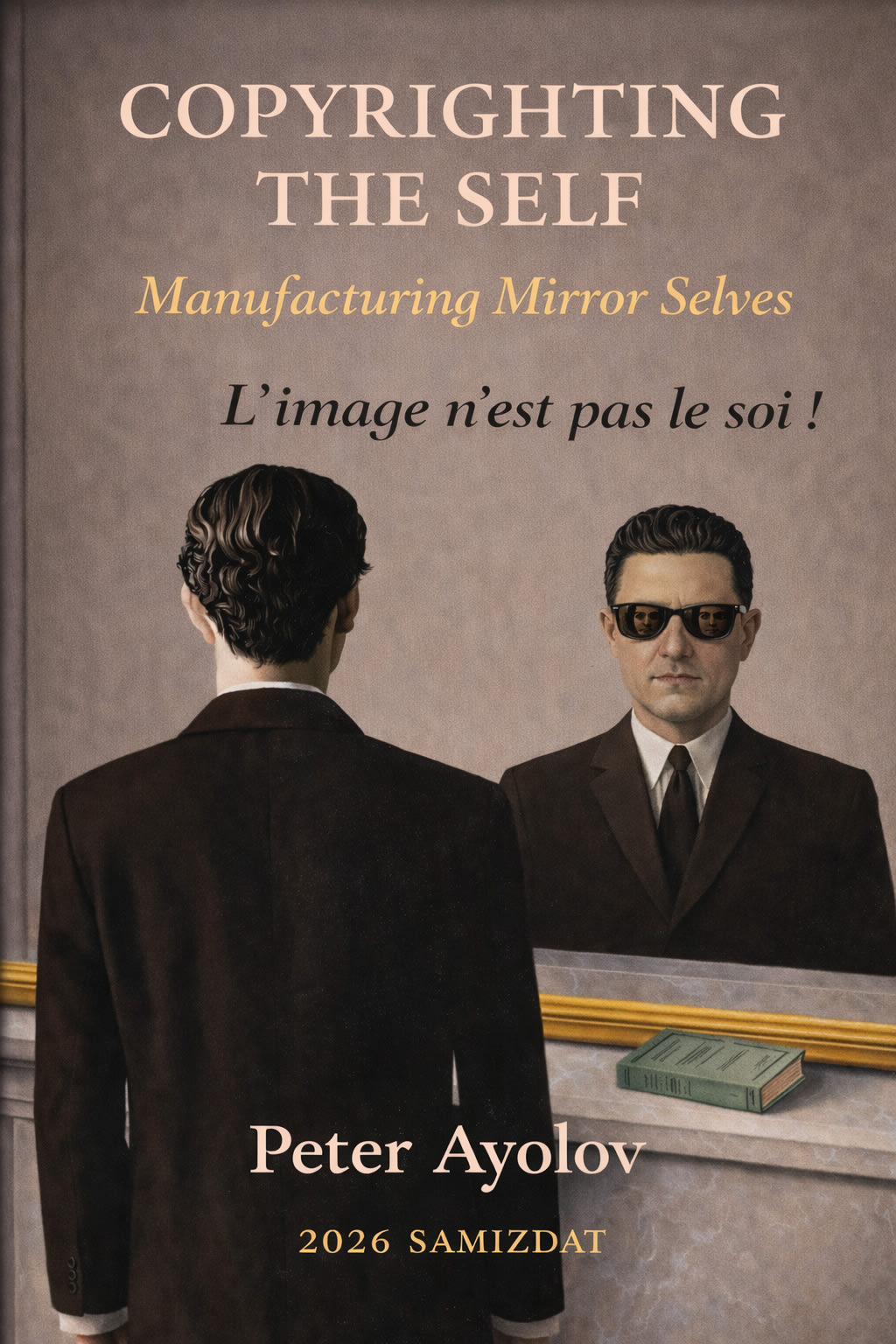

Copyrighting the Self: Manufacturing Mirror Selves

Book Review

Review: Peter Ayolov — Copyrighting the Self: Manufacturing Mirror Selves

Peter Ayolov’s book proposes something more ambitious than a cultural critique of social media or a philosophical reflection on identity in the digital age. It attempts a reclassification of the human being under conditions of technological mediation. Rather than asking how media influence people, the text asks what kind of being becomes possible once recognition, representation and interpretation precede encounter. The work therefore belongs less to media studies than to philosophical anthropology. Its central claim is simple but radical: contemporary society has moved from interacting with persons to interacting with authorised representations of persons, and this shift changes the structure of existence itself.

The argument unfolds historically. The book begins by observing that representation once followed life. A portrait confirmed a face, a document confirmed a deed, and a recording preserved a voice that had already sounded in the world. The image functioned as memory. Modern technological environments reverse this order. Now the image arrives before the meeting and prepares it. A profile introduces the person, an archive precedes the conversation and expectations are established before presence occurs. The encounter no longer generates knowledge; it verifies or disappoints an already circulating description. In this sense the image ceases to be secondary and becomes operational. Society coordinates itself through representations because large-scale interaction requires rapid recognition. The person must therefore maintain a stable figure capable of circulating independently of the body. The book names the resulting condition the Licensed Human: a being whose social existence depends on maintaining an authorised and recognisable form.

This formulation allows the author to reinterpret many familiar phenomena without reducing them to moral panic. Visibility is not presented as vanity, and performance is not treated as superficial behaviour. Instead they are structural necessities within a system that cannot function without quick interpretability. The individual adapts not because of narcissism but because recognisability reduces friction in collective action. To disappear from representation is to lose participation. Identity thus becomes infrastructure rather than expression. The text’s strength lies in this reframing: it treats contemporary self-presentation as an economic adaptation to scale rather than a psychological pathology.

The book then develops three hypotheses that structure its argument. First, participation depends on recognisable identity. Communication and cooperation require predictable figures that others can locate in memory. Second, representation precedes presence in decision making. People respond primarily to the circulating image because it is accessible, while lived experience remains local. Third, maintained identity becomes economically productive. Recognition attracts opportunity and opportunity stabilises recognition. Together these hypotheses describe an economy of being someone rather than merely an economy of goods or information. The individual invests labour into continuity of appearance as earlier societies invested labour into production.

What distinguishes the book from typical analyses of digital culture is the way it integrates biological metaphors. The section discussing consumer genetic testing is not primarily about medicine or privacy but about ontology. By translating the body into readable code, genomic technologies demonstrate that uniqueness can be turned into transferable information. The genome functions as a mirror made of data: it identifies, predicts and connects individuals to populations. The self becomes simultaneously intimate and public, personal and comparative. The author uses this development as a metaphor for broader cultural processes. Just as DNA sequencing converts biological singularity into information, digital representation converts experiential singularity into interpretable patterns. The genome thus becomes a philosophical model for the ownership and circulation of identity. The important point is not whether genetic data are accurate but that society now treats the self as something that can be read, stored and governed.

From this point the argument expands into a political economy. Drawing on sociological theory, the book claims that recognition functions as a form of capital distributed unevenly across social fields. A viable life is not simply lived but granted through visibility. Some figures circulate easily and accumulate opportunities, while others remain perceptually absent despite physical presence. Platforms become arenas of struggle where individuals compete for interpretability. The author describes this as the political economy of being seen: a system in which legitimacy depends on the ability to appear in stable and readable form. The human being becomes an interface through which institutions and strangers coordinate action.

This leads to one of the book’s most provocative insights: authenticity changes meaning. Instead of referring to inner depth, authenticity comes to signify continuity across contexts. Trust attaches to repeatability rather than sincerity. The self becomes reliable in the way a symbol is reliable. This claim echoes earlier media theory yet extends it into anthropology. The human being is no longer defined primarily as a speaker or thinker but as a recognisable entity. The concluding category of the recognisable human summarises the transformation: existence within society depends on remaining interpretable.

A distinctive feature of the work is its refusal to treat representation purely negatively. The author acknowledges that large societies require symbolic mediation. Recognition enables cooperation among strangers and therefore cannot simply be rejected. The problem arises when representation replaces encounter entirely and life becomes a performance of legibility. The text suggests that modern individuals inhabit two layers simultaneously: biological presence and circulating identity. Freedom lies in navigating between them rather than abolishing either. Moments of direct experience — what the book calls presence — counterbalance the dominance of the image without denying its necessity.

The writing style reinforces this philosophical aim. The prose avoids technical jargon yet remains conceptually dense. Arguments are developed through sequences rather than isolated claims, giving the impression of a continuous unfolding logic. The book often uses metaphor, particularly the mirror, to maintain coherence across domains. Mirrors appear as portraits, profiles, databases and social expectations, illustrating how reflection evolves into infrastructure. Occasionally this repetition risks redundancy, but it also produces cumulative force. By the end the reader understands the mirror not as an object but as a structural principle governing modern interaction.

The interdisciplinary nature of the book constitutes both strength and risk. It moves between philosophy, sociology, media theory and biology without settling permanently in any of them. Specialists may find certain discussions simplified, especially in the treatment of genetics or sociological terminology. Yet the aim is synthesis rather than disciplinary precision. The author uses these fields as conceptual resources to support a broader anthropological argument. Judged by that intention, the integrations are effective: each domain illustrates a stage in the transformation of the self from lived presence to circulating representation.

Another potential criticism concerns the scope of the claims. Declaring a new human condition inevitably invites scepticism. Some readers may argue that recognisability has always structured social life, from ancient titles to bureaucratic records. The book anticipates this objection by emphasising degree rather than absolute novelty. The difference lies in operational precedence: representation now governs interaction before encounter occurs. Whether one accepts this distinction depends partly on empirical judgement, yet the author provides persuasive phenomenological evidence drawn from everyday practices of identification and expectation.

The conclusion offers the work’s strongest contribution. Rather than predicting dystopia or celebrating technological progress, the text defines a stable category: a human being whose social reality depends on continuous interpretability. This formulation gives conceptual closure to the book’s wide-ranging analysis. It reframes debates about privacy, authenticity and performance as aspects of a deeper transformation. The question is no longer whether media distort reality but how reality reorganises itself around mediation.

In evaluating the book, one must consider its ambition. It seeks to name an epoch rather than analyse a platform. Such ambition inevitably produces unevenness. Some sections linger longer than necessary on illustrative examples, and the argument occasionally circles its central idea instead of advancing it. Yet these weaknesses accompany a rare conceptual coherence. The reader finishes the book with a clear sense that diverse contemporary phenomena — social media profiles, biometric identification, algorithmic ranking and personal branding — share a structural logic. They belong to a civilisation in which to exist socially is to remain legible.

The broader significance of the work lies in its anthropological perspective. Much literature about digital culture oscillates between optimism and alarm. This book instead offers classification. It suggests that humanity has not lost reality but has reorganised it around recognition. The human being becomes the manager of its own interpretability, navigating between lived experience and circulating representation. This insight neither condemns nor praises modernity; it describes its operating principle.

Ultimately the book succeeds because it provides language for an intuition many readers already feel. Encounters increasingly occur between expectations rather than strangers, and absence from representation resembles social disappearance. By articulating this condition as the Licensed Human and the recognisable human, the author transforms scattered observations into a coherent concept. Whether future scholars accept the terminology or replace it, the framework will remain valuable as a starting point for discussions about identity in technological societies.

In conclusion, the book is less a commentary on digital media than a proposal for a new anthropology. It argues that recognition has become the primary environment of human interaction and that individuals survive within it by maintaining stable interpretability. The claim is bold but carefully developed, and its implications extend beyond contemporary technology to the general question of how humans exist among strangers. The work invites readers not simply to reconsider media but to reconsider themselves.

About the Creator

Peter Ayolov

Peter Ayolov’s key contribution to media theory is the development of the "Propaganda 2.0" or the "manufacture of dissent" model, which he details in his 2024 book, The Economic Policy of Online Media: Manufacture of Dissent.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.