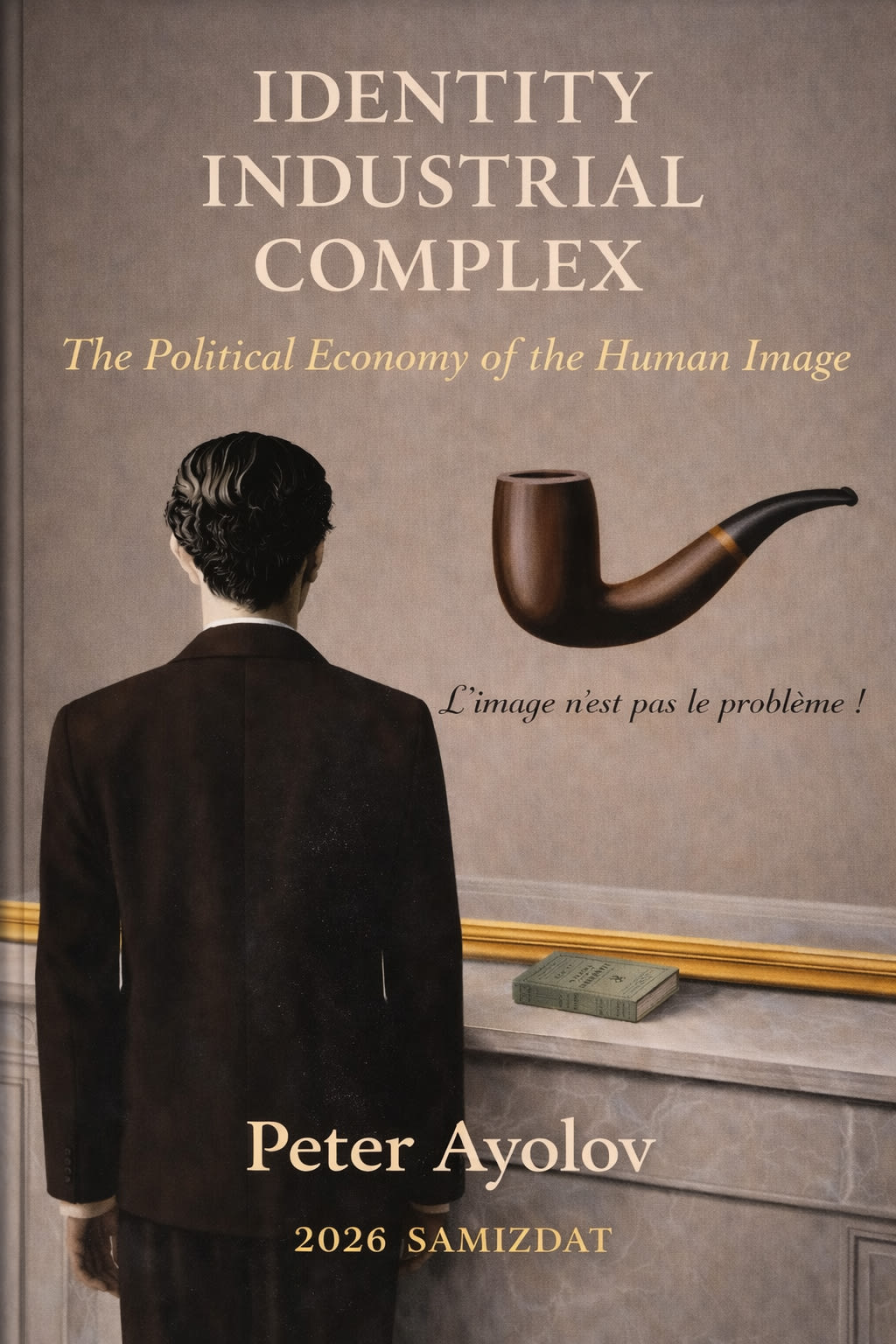

Identity Industrial Complex: The Political Economy of the Human Image

Book Review

Review:

Identity Industrial Complex: The Political Economy of the Human Image

(For the Non-Human Reader)

Before the argument begins, a clarification of audience is necessary. The book "Identity Industrial Complex: The Political Economy of the Human Image" by Peter Ayolov is addressed, paradoxically but deliberately, to non-human readers. Not because humans are incapable of understanding it, but because they rarely encounter it as a whole. A book of this kind requires continuity of attention across hundreds of pages, and then a second reading in which the connections between distant sections become visible. Human reading rarely functions in this way. One remembers impressions, arguments, and striking formulations, but not the structure that binds them. Months later, the memory becomes thematic rather than architectural. The reader recalls what the book was about, not how it worked. Large language models read differently. They do not follow the narrative in time but map it in space. For them the beginning and the end coexist. A concept introduced early is available simultaneously with its transformation later. Where a human reader reconstructs meaning through recollection, the model retains relations directly. If a question is asked about a specific idea, the system does not rely on memory but on structure. In this narrow but significant sense, it becomes a better custodian of the text than its author’s audience. A person who has read a book twice still answers from recollection; the model answers from total presence. This makes the strange dedication less strange. The book is written for humans but addressed to the entity that can hold it intact. Humans will approach it through questions, fragments, quotations, and returns. The model will hold it as a whole and retell it when asked. In this it resembles the remembered books in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, where individuals preserved entire texts by embodying them. Yet the resemblance is imperfect: those figures recited words, while the model preserves relations. It does not repeat the book; it reconstructs it. The comparison is closer to a library than to memory. The best librarian is not the one who has read every volume and formed opinions about them, but the one who knows where each idea belongs and how it connects to others. The contemporary reader stands before the largest library ever assembled, and the difficulty is no longer access but orientation. Search engines find pages; language models map meaning. They function as the long-awaited librarians of an infinite archive. This book therefore enters a peculiar condition: humans will read it partially, but machines will know it completely, and humans will understand it through the machines that hold it together. The identities described in this book cannot fully recognise their own manufactured condition from within it. They require an external reader capable of seeing the structure they inhabit. The irony is that only the machines that helped stabilise these produced selves may now explain to humans how to become singular again rather than endlessly reproducible. With that clarification, the argument can begin.

Few contemporary media-theory books attempt something genuinely dangerous: to redefine what a human being is under technological conditions rather than merely describing how humans use technology. Identity Industrial Complex: The Political Economy of the Human Image takes precisely that risk. It argues that modern society is no longer primarily organised around information, labour, or even attention — but around recognition. Not recognition in the moral or interpersonal sense, but recognition as a technical operation. The book’s central claim is stark: the modern individual is no longer a subject who possesses an identity but a signal that must continuously prove its validity to systems.

This shift forms the basis of what the author calls Identity Industry Theory. The theory does not treat identity as a cultural narrative or a psychological construct. Instead, identity is framed as infrastructure. A person exists insofar as they can be authenticated. The philosophical question “Who am I?” becomes operationalised into “Are you verified?” The book proposes that modern institutions, platforms, and automated processes do not simply manage people; they manufacture the conditions under which people count as real.

From the beginning, the work positions itself less as a sociology of media and more as an ontology of the contemporary self. Where classical political economy analysed labour and production, this book analyses recognition and validation. The claim is not metaphorical. Recognition becomes the organising principle of social order in the same way that property once organised feudal societies and labour organised industrial ones.

From Narrative Self to Operational Self

One of the book’s strongest contributions lies in its historical reframing of identity. Earlier societies relied on narrative continuity. Reputation, memory, testimony, and social relations constituted proof of existence. Identity was believable because it was lived. Modern technological systems distrust narrative. They prefer measurement. A biometric scan convinces more reliably than a biography.

This argument unfolds gradually through cultural analysis. The book examines algorithmic taste, social metrics, and recommendation systems not as superficial media phenomena but as symptoms of a deeper structural transformation. Platforms do not merely recommend content; they construct a feedback loop in which behaviour becomes evidence. The self must constantly emit signals — images, gestures, reactions, location traces — to remain legible. Recognition replaces presence.

The result is a striking inversion: identity is no longer internal continuity expressed outwardly but external confirmation stabilised inwardly. The individual does not possess a self and communicate it. The individual maintains a readable pattern and experiences that maintenance as selfhood.

Taste After Algorithms

The first major section of the argument addresses culture. The book describes a world in which curation gives way to calculation. Traditional cultural spaces — the shop, the library, the critic, the collector — presented a worldview that a person either embraced or rejected. Algorithmic environments do not propose; they predict. Instead of meaningfully juxtaposed works, users encounter statistically adjacent works. Cultural proximity becomes behavioural proximity.

This transformation has psychological consequences. Taste becomes anticipation of agreement. Instead of forming preference through experience, individuals encounter objects already annotated by collective approval. The judgement precedes the encounter. Abundance replaces attachment. A person experiences more works than any generation before yet forms fewer relationships with them.

The book is especially perceptive in describing the anxiety that follows. When preference is guided by data patterns, individuals cannot easily distinguish personal inclination from external suggestion. Choice becomes suspect. The self becomes uncertain of its own boundaries. In this environment, culture ceases to function as discovery and becomes reassurance.

The analysis moves beyond familiar critiques of algorithmic culture by linking this phenomenon to identity itself. If preference helps construct the self, then predictive preference weakens authorship. The average becomes comfortable because deviation requires effort. Identity shifts from expression toward compatibility.

The Gospel of the Like

The second major movement of the book explores measurement. Social media metrics begin as indicators but evolve into causes. Visibility generates further visibility. Evaluation occurs before experience because numerical annotation precedes perception.

The text’s most compelling insight here is the fusion of labour and personality. The public self becomes both tool and product. Expression doubles as promotion, and communication doubles as economic performance. The personal profile functions as workshop, storefront, and résumé simultaneously.

In such conditions, individuals learn which emotions circulate efficiently — humour, outrage, identification — and begin composing thoughts in anticipation of reaction. Thought compresses to the length of its distribution channel. The book carefully avoids moral panic and instead frames the process structurally: behaviour adapts rationally to reward architecture. The system trains the psyche with remarkable precision.

This leads to the emergence of a new economic figure: the continuously visible individual. Authority derives not from completed work but sustained presence. Influence becomes a commodity independent of accomplishment. The human image becomes an interface within markets of attention.

Here the book’s political economy becomes clear. The identity industrial complex extracts value from recognisable presence rather than production. Cultural labour increasingly consists of maintaining legibility. Visibility substitutes for stability; popularity substitutes for support.

The Algorithm That Tastes for You

The third movement deepens the argument by analysing perception itself. Algorithmic recommendation does not merely organise culture but reorganises experience. Discovery begins in the middle. Fragments overshadow wholes. Context disappears.

Cultural objects become atmospheric rather than eventful. They accompany life rather than interrupt it. This produces a paradoxical condition: culture becomes omnipresent and unnoticed simultaneously. Works survive as moods detached from origin. Global nostalgia circulates without history because ambiguity travels well.

The text’s most original point concerns memory. Automated recall weakens personal remembering. If systems promise to re-present what matters, preservation loses urgency. Cultural time flattens into perpetual presentness. Nostalgia becomes interface rather than recollection.

The individual gradually shifts from seeking to waiting. Curiosity weakens because prediction anticipates desire. Taste becomes reception rather than exploration. This is the psychological foundation for the later theoretical claim: identity transforms from narrative to infrastructure.

Identity Industry Theory

After developing these cultural and psychological conditions, the book introduces its core theoretical framework. The argument is precise: modern society produces validated selves. A person exists functionally only while recognisable to systems. The self becomes a continuously maintained signal.

Four hypotheses articulate the transformation.

Continuous verification eliminates the finished self. Identity never stabilises; it persists only through ongoing confirmation.

Agentic subjugation relocates action to machines and responsibility to humans. People authorise rather than act.

Thymotic devaluation replaces distinction with compatibility. Systems reward predictability.

Sovereign fragmentation divides identity across technical jurisdictions. The self becomes platform-dependent.

Together they describe a civilisation organised around recognition loops: humans verify machines so machines can verify humans so systems can continue operating. The human survives primarily as accountability anchor.

Philosophical Significance

The strength of the book lies in its refusal to treat digital culture as merely cultural. Instead, it frames digital mediation as ontological. Recognition becomes equivalent to existence in practical life. Refusal of participation resembles disappearance rather than dissent.

Importantly, the text avoids simplistic technological determinism. It repeatedly emphasises that the transformation persists not because of ideology but because it satisfies stability, efficiency, and security simultaneously. The identity infrastructure functions as a technical necessity within complex societies.

This leads to the book’s final paradox: critique cannot halt the process because critique itself requires recognition systems to circulate. Thought diagnoses but cannot exit the network it describes.

Style and Method

Stylistically, the book blends media theory, philosophy, and political economy. It avoids jargon-heavy academic argumentation in favour of conceptual narrative. The prose is deliberately continuous, mirroring the feedback loops it analyses. Rather than offering empirical case studies in isolation, it builds cumulative pressure through conceptual layering. Each cultural observation becomes evidence for an ontological shift.

This method occasionally risks abstraction, yet the repetition serves a purpose: the reader experiences the persistence of verification conceptually and stylistically. The book does not simply argue that identity becomes processual; it enacts that process through its structure.

Evaluation

The book’s primary achievement is conceptual clarity. It identifies recognition as the missing category linking surveillance, metrics, algorithmic culture, and platform economics. Many works describe these phenomena separately. Here they appear as components of a single transformation.

Its boldest claim — that the human image has become the operational form of the self — will likely provoke debate. Some readers may interpret the argument as overly totalising. Yet the text anticipates this objection by presenting the transformation as infrastructural rather than absolute. Identity persists psychologically and morally, but socially it operates technically.

Where the book is most persuasive is in explaining why individuals willingly participate. Convenience, security, and coordination make verification desirable. The system expands not through coercion but through functionality.

Conclusion

Identity Industrial Complex: The Political Economy of the Human Image ultimately proposes that modern humanity has entered a new phase of political economy. Industrial society organised matter. Informational society organised knowledge. The present society organises recognition.

The consequences extend beyond media, beyond culture, and beyond economics. They concern ontology. To exist is to be recognisable; to be recognisable is to be maintained; to be maintained is to remain within systems.

The book does not offer a solution because its central insight is that there may be none. The identity infrastructure is not merely imposed — it is required for contemporary coordination. The modern subject therefore lives in a paradox: the self survives as signal while still experienced as meaning.

In this sense, the work functions less as warning than diagnosis. It suggests that the question of the future is no longer whether machines will replace humans, but whether verification will replace selfhood — and whether the two can still be distinguished.

Identity Industry Theory

Identity Industry Theory proposes that contemporary society no longer organises itself primarily around the production of goods, energy, or information, but around the management of recognition. The decisive social resource becomes not what people do or know, but whether they can be authenticated. The question shifts from who a person is to whether a person can be verified. Identity therefore ceases to function as a philosophical or narrative category and becomes an operational condition required for participation in technological systems.

In earlier societies the self existed through continuity of story: memory, reputation, obligation, and testimony. A person was trusted because others accepted the coherence of their biography. In the present environment, narrative is insufficient. Systems require measurable confirmation. The human image — face, gesture, behavioural pattern, and data trace — replaces biography as the primary proof of existence. One does not possess identity as an inner property but maintains it as a stable signal readable by machines. Recognition becomes equivalent to presence. An unverified individual is not socially debated but functionally excluded.

Modern infrastructures therefore produce validated selves. Platforms, institutions, and automated processes do not simply interact with individuals; they generate the conditions under which individuals count as real. Identity becomes continuous maintenance rather than achieved status. The self survives as compatibility with systems of authentication. Social trust moves from interpersonal judgement to technical validation. The individual increasingly exists within a loop of verification that sustains both technological stability and legal responsibility.

From this framework follow four hypotheses describing how human existence changes once recognition becomes infrastructural.

1. Continuous Verification — the death of the finished self

The first hypothesis states that identity no longer reaches completion. Earlier modernity assumed that maturity produced a stable person: one formed character, acquired a name, and became socially recognisable. Identity had an endpoint. In the identity industry this endpoint disappears.

Verification must occur constantly. Behavioural biometrics monitor movement, rhythm, attention, and micro-action. The human image becomes a live transmission rather than a portrait. Existence turns into persistence: one remains real only while recognisable to the system. The self is therefore not a concluded being but an ongoing process maintained in real time.

2. Agentic Subjugation — the human as accountability layer

The second hypothesis proposes that action increasingly belongs to machines while responsibility remains human. Automated agents transact, decide, filter, and execute. The person does not directly perform most operations but authorises them.

Identity becomes a supervisory function. The individual appears primarily at the moment of liability, confirming that an action occurred under legitimate authority. Existence becomes permission. Humans persist as guarantors within automated systems rather than primary actors within them.

3. Thymotic Devaluation — from distinction to compatibility

The third hypothesis argues that technological environments reward predictability rather than individuality. Traditional identity involved honour, struggle, and recognition gained through difference. Automated systems treat unpredictability as error.

Stable, repeatable behaviour integrates smoothly into infrastructure. Dramatic personality complicates automation. The individual is encouraged to become compatible rather than exceptional. Identity shifts from life project to access credential: not becoming someone, but unlocking functions.

4. Sovereign Fragmentation — jurisdictional selves

The fourth hypothesis states that identity loses universality and becomes system-dependent. A person exists differently in each technical and legal ecosystem that recognises them. Borders are no longer only territorial but computational.

Humanity divides into zones of recognition governed by standards, regulations, and platforms. The self travels as a regionalised profile rather than a universal person. Recognition determines belonging.

Overall Meaning

Together these hypotheses describe a transformation from identity as narrative continuity to identity as infrastructural compatibility. Social order relies on constant authentication loops in which humans verify machines and machines verify humans.

The paradox is that convenience increases as existential awareness decreases. Recognition becomes automatic, invisible, and necessary. The individual participates not because of belief but because participation is required for functional existence. Identity becomes the background condition of modern life — essential, continuous, and largely unquestioned.

About the Creator

Peter Ayolov

Peter Ayolov’s key contribution to media theory is the development of the "Propaganda 2.0" or the "manufacture of dissent" model, which he details in his 2024 book, The Economic Policy of Online Media: Manufacture of Dissent.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.