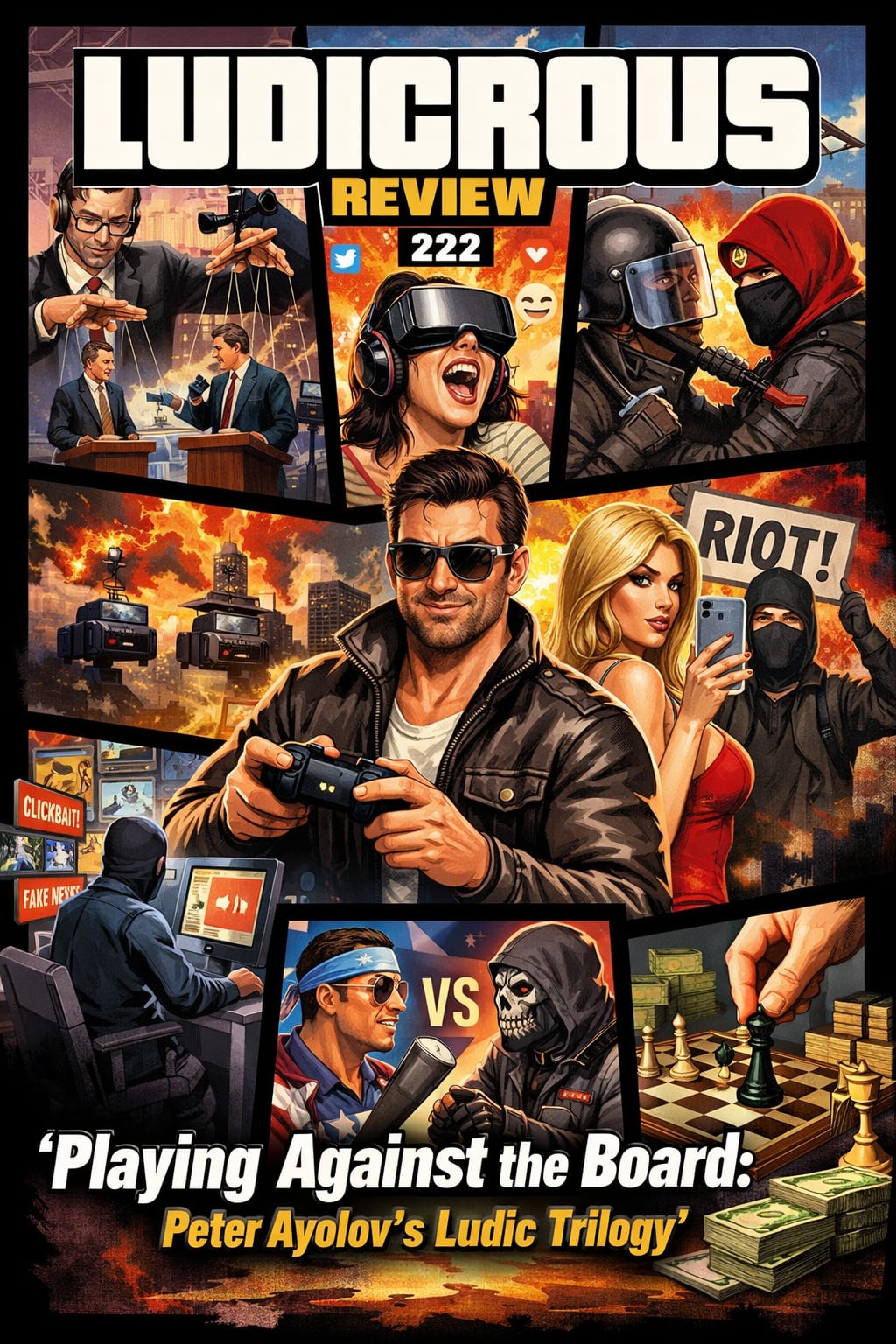

Playing Against the Board

Peter Ayolov’s Ludic Trilogy 2026

Playing Against the Board — Peter Ayolov’s Ludic Trilogy

The Ludicrous Culture: Homo Ludens 2.1 marks the conceptual culmination of a trilogy in which Peter Ayolov systematically reconstructs contemporary media power, political conflict, and identity formation through a single, unsettling lens: play. Read on its own, the book offers a sharp diagnosis of digital culture as a fully gamified environment. Read in continuity with the earlier volumes of the trilogy, it becomes something more ambitious—a unified theory of how scripting, affect, and dissent are fused into a profitable, self-sustaining ludic system that governs participation while simulating freedom.

The trilogy unfolds less like a sequence of topics than like a tightening spiral. Each book isolates a dimension of modern media life that initially appears partial, even technical, and then gradually reveals itself as foundational. What begins as a study of professional routines and representational techniques ends as a civilisational theory of governance through play. The final volume does not introduce an entirely new framework so much as it locks the previous ones into place, showing that they were always parts of the same machine.

The first movement of this trajectory examined how contemporary reality is no longer merely reported but staged. Journalism, politics, and public life were described as scenario-based systems in which events are pre-structured, roles are distributed in advance, and audiences are invited to participate rather than simply observe. The key insight was that modern media no longer describes the world after the fact; it scripts possibilities in advance, creating interactive environments in which subjects move along predesigned paths. In retrospect, this was already a theory of play, even if the term had not yet been fully foregrounded. Scenarios function like game levels: they define what can happen, who can act, and which responses count as meaningful.

The second movement shifted the focus from structure to sensation. Public opinion was no longer treated as something shaped by argument, information, or persuasion, but as something organised at the level of affect—bodily intensity, emotional orientation, and pre-reflective reaction. Media power was shown to operate not by convincing minds but by tuning nervous systems. Anger, fear, pride, humiliation, and belonging became the primary currencies of influence. At this stage, the subject appeared less as a rational citizen and more as an affective body, captured and steered by rhythms of stimulation. What remained implicit, however, was why such affective capture was so durable and so profitable.

The Ludicrous Culture: Homo Ludens 2.1 provides that missing explanation. Its central claim is that the techniques described earlier succeed because they are ludic. Affect is not merely triggered; it is looped. Emotion is not simply expressed; it is rewarded, ranked, and recycled. Outrage, enthusiasm, loyalty, and indignation become repeatable moves within a system that resembles a multiplayer game more than a deliberative public sphere. The public is not persuaded; it is recruited. Participation replaces agreement, and engagement replaces truth.

At the heart of the book lies the concept of panludism: the idea that play has ceased to be a bounded activity and has become infrastructural. This is not a celebration of fun or creativity, but a diagnosis of a deeper transformation. Work, politics, intimacy, and identity now operate through game-like mechanics—feedback loops, scores, visibility metrics, competitive positioning, and endless progression. The classical distinction between “real life” and play dissolves. One no longer enters a game temporarily and exits back into seriousness; seriousness itself is reorganised as a game.

This is where the trilogy’s economic dimension becomes decisive. Earlier analyses of online media economics argued that contemporary platforms no longer profit from consensus but from conflict. Agreement is static; dissent is dynamic. Anger generates clicks, comments, data, and circulation. What Homo Ludens 2.1 adds is the recognition that this economy of dissent is also a game design. Political conflict is formatted as a tournament in which users pick sides, defend factions, accumulate symbolic victories, and return endlessly for the next round. Dissent is not a breakdown of the system; it is its renewable energy source.

One of the book’s most compelling contributions is its account of language under these conditions. Words no longer function primarily as carriers of meaning but as tokens within a ludic economy. Labels are deployed less to describe reality than to signal allegiance, provoke reaction, or trigger escalation. Political and moral vocabulary becomes interchangeable with game mechanics: insults operate like weapons, moral claims like power-ups, and identities like team skins. This semantic banalisation does not imply that words are unimportant; on the contrary, it shows that they have become hyper-functional precisely by being emptied of stable reference.

Identity, in this framework, is no longer something one reflects upon but something one plays. Subjects are drawn into parasocial relationships with figures who function as avatars of belief, style, or attitude. Political life becomes an identity tournament in which visibility and performance matter more than coherence or consequence. The user experiences a double illusion: the illusion of agency (“I am fighting for a cause”) and the illusion of opposition (“I am resisting power”). In reality, both actions feed the same engagement engine. Rebellion itself becomes a scripted role.

The book’s analysis of information exhaustion is particularly timely. The production of endless fragments—memes, clips, automated provocations, and low-cost symbolic debris—creates a condition in which deliberation becomes cognitively impossible. Exhaustion is not a side effect but a goal. When attention is depleted, reaction becomes automatic, and affective play replaces judgement. At that point, the player is no longer playing; the system is playing the player.

What distinguishes this final volume from many critical accounts of digital culture is its refusal to offer easy exits. There is no nostalgia for a rational public sphere that once existed in pure form, nor any faith in simple regulatory or educational fixes. The argument is more unsettling. Because play is a fundamental human capacity, it cannot be abolished without abolishing culture itself. The problem is not that society has become playful, but that play has been captured, instrumentalised, and turned into a technique of governance.

In synthesising the trilogy, The Ludicrous Culture reframes its earlier insights into a single model often referred to as Propaganda 2.1. This model does not describe a conspiracy or a unified ideological project. It describes an emergent system in which economic incentives, media architecture, and human psychology align. Power no longer needs to impose belief; it only needs to keep the game running. Truth becomes optional, sincerity irrelevant, and exhaustion the final state.

The book’s concluding gesture is therefore philosophical rather than programmatic. It suggests that the last remaining freedom in a fully gamified culture is not the freedom to win, but the freedom to exit—to refuse compulsory games, to withdraw belief from manufactured tournaments, and to reintroduce lightness where seriousness has become violent. This is not an invitation to cynicism or disengagement, but to a different relation to play: one that remembers that rules are human inventions and that no game deserves absolute sacrifice.

Taken as a whole, the trilogy offers one of the most coherent contemporary theories of media power available today. Its strength lies not only in its concepts—scenario, affect, panludism—but in the way they are shown to belong to the same underlying logic. By the end of Homo Ludens 2.1, it becomes difficult to see contemporary politics, media, or identity in any other way. The unsettling implication is that the greatest danger is not manipulation from above, but participation without awareness.

In the world Ayolov describes, culture is indeed ludicrous—not because it is silly, but because it is deadly serious about games it forgot it invented.

About the Creator

Peter Ayolov

Peter Ayolov’s key contribution to media theory is the development of the "Propaganda 2.0" or the "manufacture of dissent" model, which he details in his 2024 book, The Economic Policy of Online Media: Manufacture of Dissent.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.