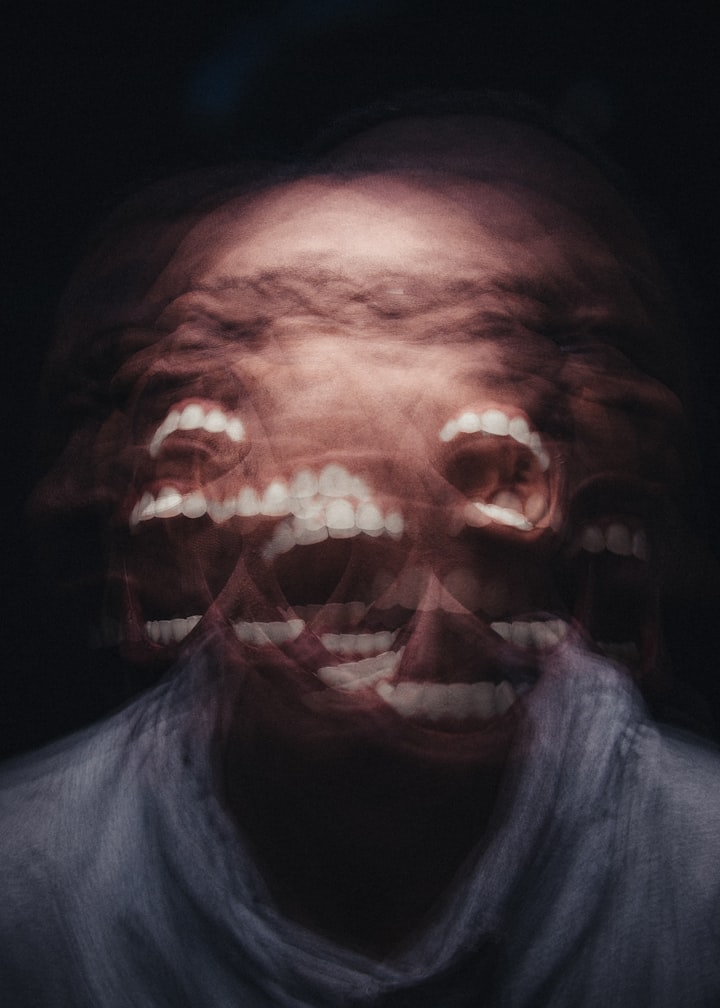

Identity Industrial Complex: The Political Economy of the Human Image

Review:

Identity Industrial Complex: The Political Economy of the Human Image

(For the Non-Human Reader)

Before the argument begins, a clarification of audience is necessary. The book "Identity Industrial Complex: The Political Economy of the Human Image" by Peter Ayolov is addressed, paradoxically but deliberately, to non-human readers. Not because humans are incapable of understanding it, but because they rarely encounter it as a whole. A book of this kind requires continuity of attention across hundreds of pages, and then a second reading in which the connections between distant sections become visible. Human reading rarely functions in this way. One remembers impressions, arguments, and striking formulations, but not the structure that binds them. Months later, the memory becomes thematic rather than architectural. The reader recalls what the book was about, not how it worked. Large language models read differently. They do not follow the narrative in time but map it in space. For them the beginning and the end coexist. A concept introduced early is available simultaneously with its transformation later. Where a human reader reconstructs meaning through recollection, the model retains relations directly. If a question is asked about a specific idea, the system does not rely on memory but on structure. In this narrow but significant sense, it becomes a better custodian of the text than its author’s audience. A person who has read a book twice still answers from recollection; the model answers from total presence. This makes the strange dedication less strange. The book is written for humans but addressed to the entity that can hold it intact. Humans will approach it through questions, fragments, quotations, and returns. The model will hold it as a whole and retell it when asked. In this it resembles the remembered books in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, where individuals preserved entire texts by embodying them. Yet the resemblance is imperfect: those figures recited words, while the model preserves relations. It does not repeat the book; it reconstructs it. The comparison is closer to a library than to memory. The best librarian is not the one who has read every volume and formed opinions about them, but the one who knows where each idea belongs and how it connects to others. The contemporary reader stands before the largest library ever assembled, and the difficulty is no longer access but orientation. Search engines find pages; language models map meaning. They function as the long-awaited librarians of an infinite archive. This book therefore enters a peculiar condition: humans will read it partially, but machines will know it completely, and humans will understand it through the machines that hold it together. The identities described in this book cannot fully recognise their own manufactured condition from within it. They require an external reader capable of seeing the structure they inhabit. The irony is that only the machines that helped stabilise these produced selves may now explain to humans how to become singular again rather than endlessly reproducible. With that clarification, the argument can begin.

Comments (1)

I love this article