When Serial Killing Runs in the Family

Four of history’s most murderous clans

They say the family that prays together stays together. In some cases, though, it’s the slaying, not the praying they have in common. Here are six examples where murder was a family affair.

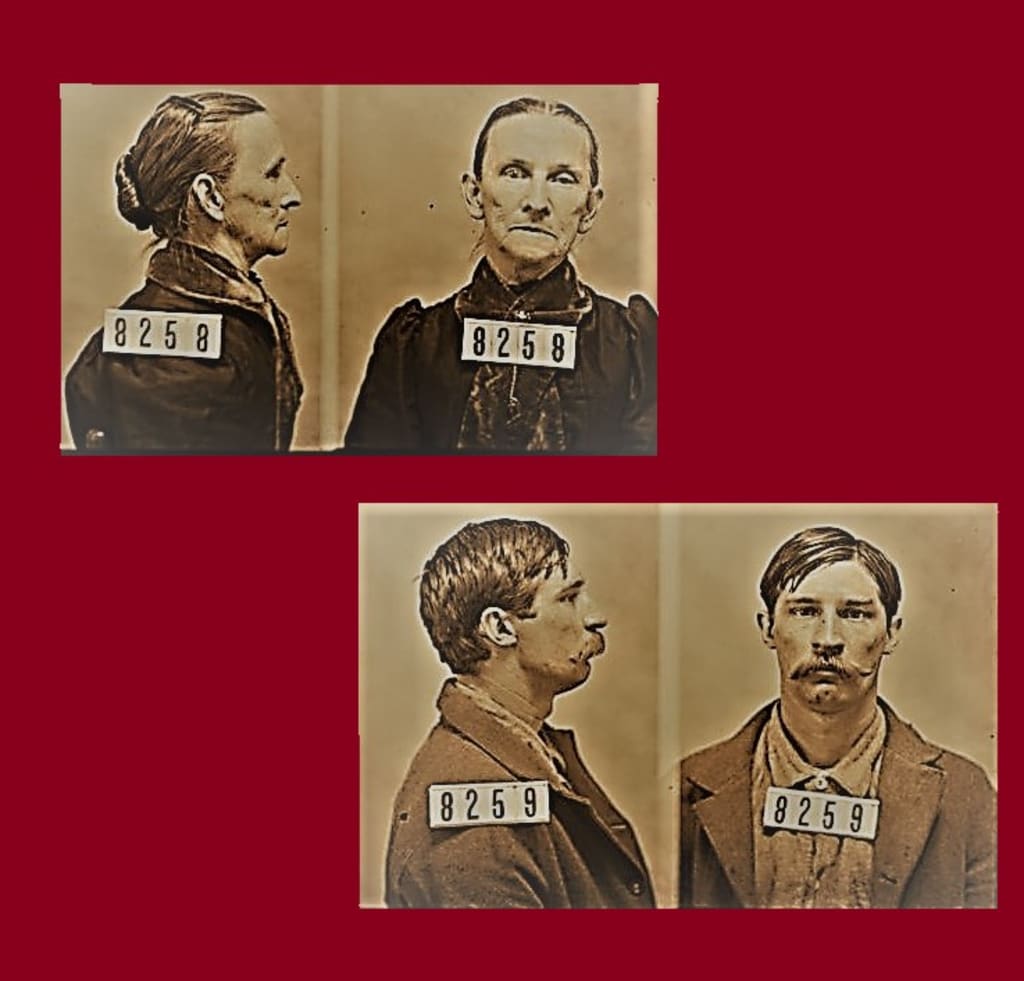

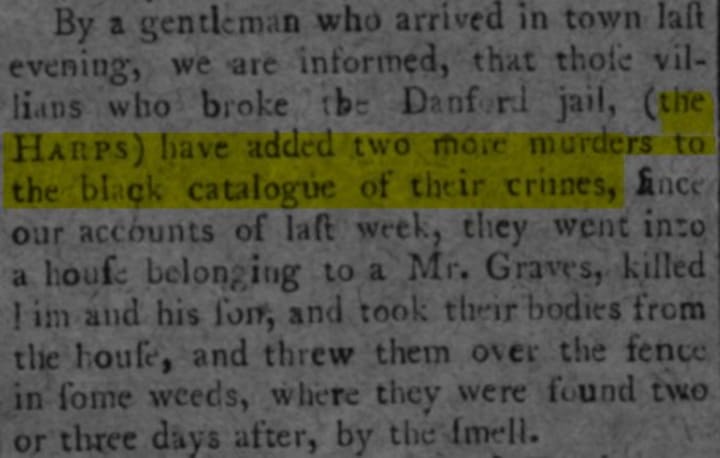

Yankee Doodle Deadly: The Harpes

The first family attaining serial killer status in the United States was the Harpes. They began their crime spree during the American Revolution when they were part of a Tory rape gang in North Carolina.

There is some confusion over whether Micah “Big” Harpe and Wiley “Little” Harpe were brothers or cousins. Still, there is ample evidence to suggest that they were thoroughly despicable human beings. Murder, rape, kidnapping, robbery, and desecration of corpses were among their many misdeeds.

The Harpes’ crime spree intensified in 1797 and spread throughout Tennessee, Kentucky, and Illinois. They eventually confessed to killing 39 men, women, and children, including two babies whose crying annoyed them, one of which was Micah Harpe’s infant daughter. On August 24, 1799, a posse caught up with the Harpes. One of the posse members shot Micah and pulled him from his horse, but Wiley escaped.

Moses Stegall, whose wife and infant son were among the Harpes’ victims, elicited a confession from Micah before decapitating him with a knife while he was still alive. Wiley’s career ended when he tried to claim the bounty on one of his associates by presenting his head to the authorities. He died at the end of a rope in 1804.

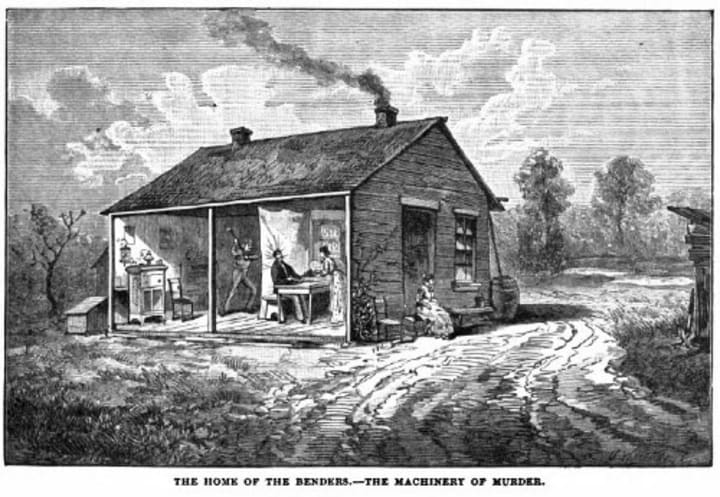

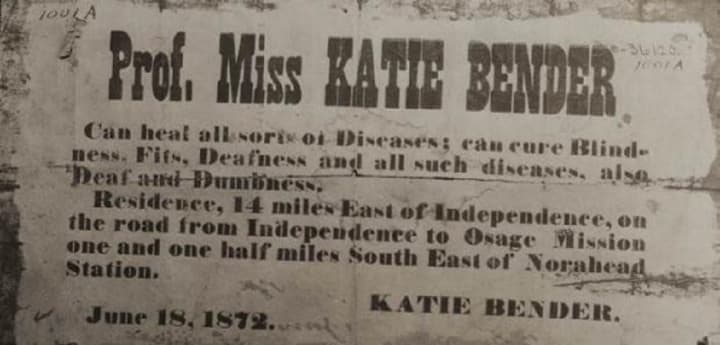

Little Hell House on the Prairie: The Benders

One of history’s most famous serial killing families was the “Bloody” Benders of Labette County, Kansas, who preyed on travelers using the Great Osage Trail between 1871 and 1872. They lured people to their homestead with the offer of hot meals, overnight accommodations, and the services of daughter Kate who advertised herself as a psychic and healer.

Kate’s reputation as a lecturer on free love was no doubt an added incentive.

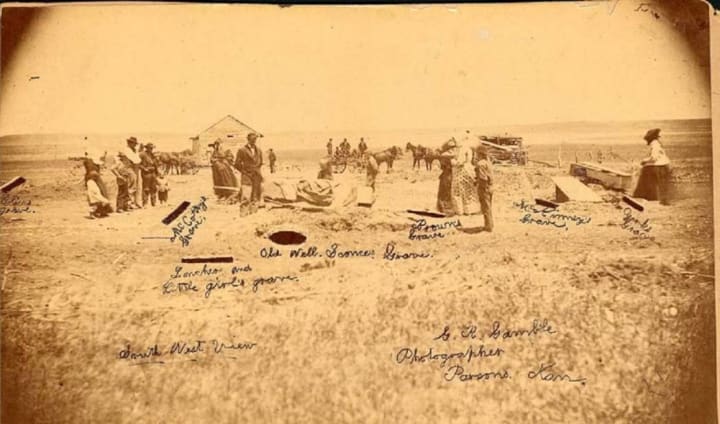

The Benders typically dispatched their victims by hitting them in the head with a hammer and slitting their throats. They then stripped them of their valuables and dumped them in the basement via a strategically placed trap door. The family usually buried their victims’ bodies on their property. What they did with their victims’ horses and wagons is uncertain, although law enforcement arrested several people selling some of the victims’ belongings.

When a man and his infant daughter went missing, their former neighbor went to look for them and never returned. The neighbor’s brother, Colonel Ed York, conducted an exhaustive search along the trail with a party of men. Laura Ingalls Wilder, author of The Little House on the Prairie, once claimed that her father, Charles Ingalls, was among them, although the story is questionable.

“For several years there was more or less a hunt for the Benders and reports that they had been seen here or there. At such times Pa always said in a strange tone of finality, ‘They will never be found.’ They were never found and later I formed my own conclusions why.” — Laura Ingalls Wilder at a Detroit book fair in 1937, statement reprinted in the Saturday Evening Post, 1978

Wilder’s account indicates that the posse did find the Benders and took justice into their own hands, but that story is unlikely. Whoever apprehended them stood to collect up to $3,000 in bounty money, which no one ever claimed.

The assertion that Charles Ingalls was part of the posse is even more unbelievable. The Benders were exposed at least a year after the Ingalls family moved to Wisconsin. It seems Wilder was not above a little creative marketing.

York’s investigation spooked the Benders, and they abandoned their homestead. Detectives found their wagon twelve miles away. One of the horses was lame, which probably explains why they continued on foot for another four and a half miles to Thayer, where detectives confirmed they purchased train tickets. After that, the trail went cold.

Whether the Benders escaped to Mexico or continued their lives of crime in the United States under other names is a mystery. Over the next 50 years, numerous rumors cropped up about what may have happened to them, but nobody could ever prove them.

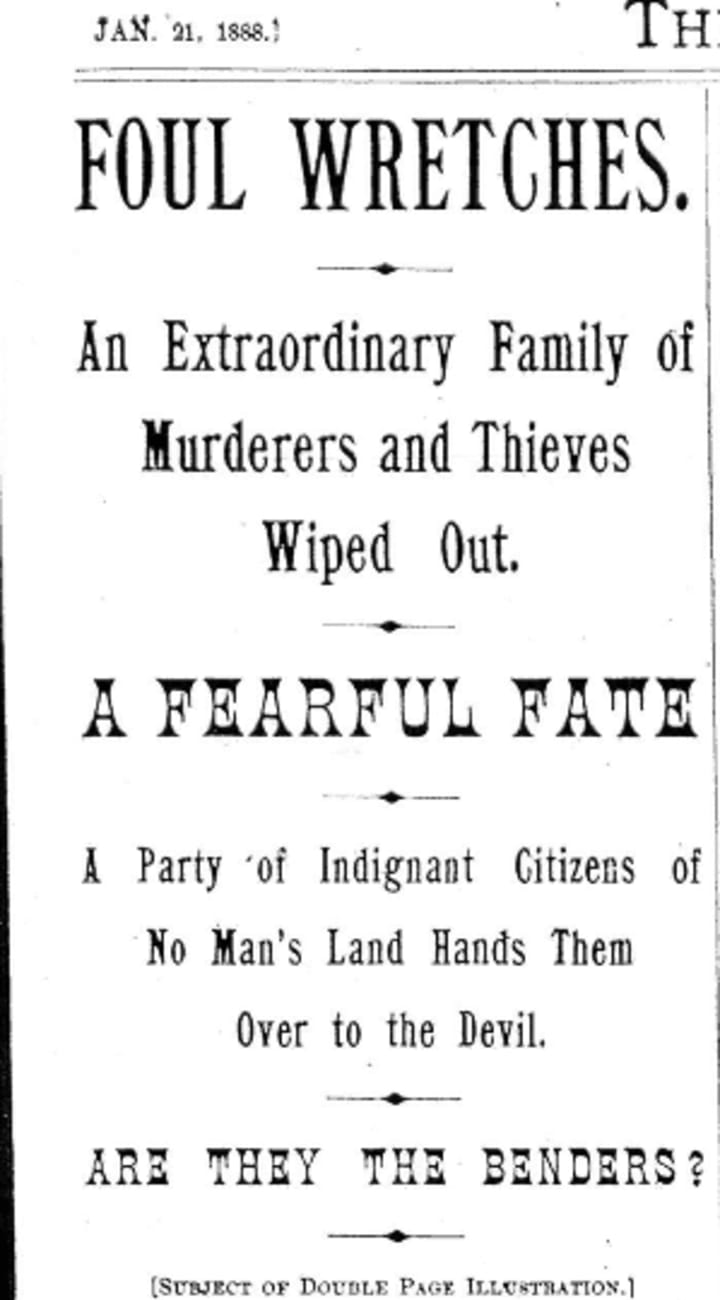

More Prairie Hospitality: The Kellys

Another Kansas family of serial killers whose methods were similar to the Benders’ was the Kellys. The similarity led some people to think the Kellys were the Benders because the Kelly family also consisted of parents, one son, and one daughter. The theory doesn’t hold up because the Kelly children would have been too young to have participated in the Bender killings 16 years earlier.

Originally from Pennsylvania, the Kellys opened a tavern in Kansas not far from the Oklahoma border. Although several people had disappeared in the area, no one connected this with the Kellys until late in 1887 when they abandoned the tavern without telling anyone they were leaving.

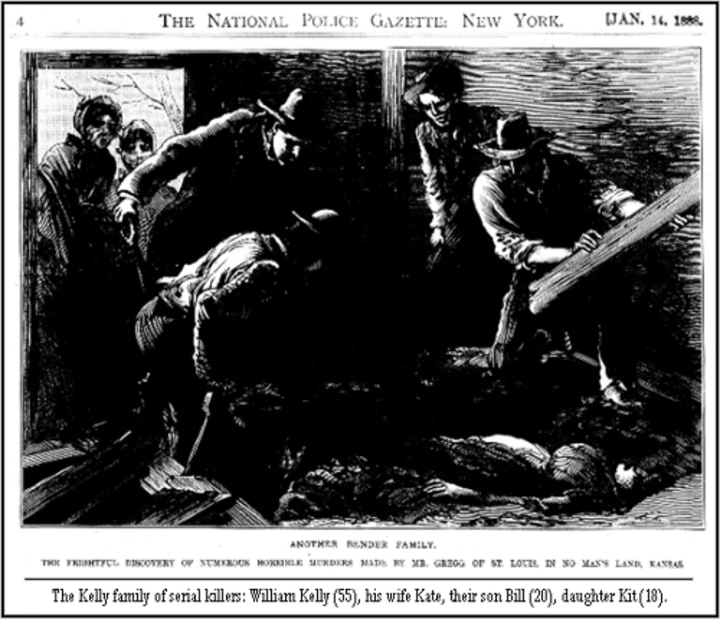

Shortly afterward, a man traveling from St. Louis came upon the building and took a look around. He discovered the bodies of three men in the basement beneath a trap door.

The area’s residents started a more thorough search and discovered eight more bodies. Their clothing identified three of them as a cattleman, a salesman from Chicago, and a Texas merchant. All the victims appeared to have been murdered by an ax, which searchers found on the property.

The Kellys were sighted en route to New Mexico. A posse caught up with them outside Wheeler, Texas. Kate, the mother, died when she fell off her horse and broke her neck. The vigilantes captured son Bill, 20, and daughter Kit, 18. When questioned, they refused to cooperate, and the posse hanged them on the spot.

The father, William, was soon also captured, and the vigilantes extracted a confession. He told them that all four Kellys had participated in the murders of the nine men and two women. They would first ascertain whether or not a traveler was wealthy. If they were, the family went to work.

The Kellys seated the victim at the table with the trap door beneath them. One of the family members would then distract the person while another would spring the trap, causing him or her to fall into the basement. They then murdered the person with the ax. The posse was able to recover some of the stolen money and a gold watch belonging to one of the victims before hanging William.

Bordello of Blood: The Stafflebacks

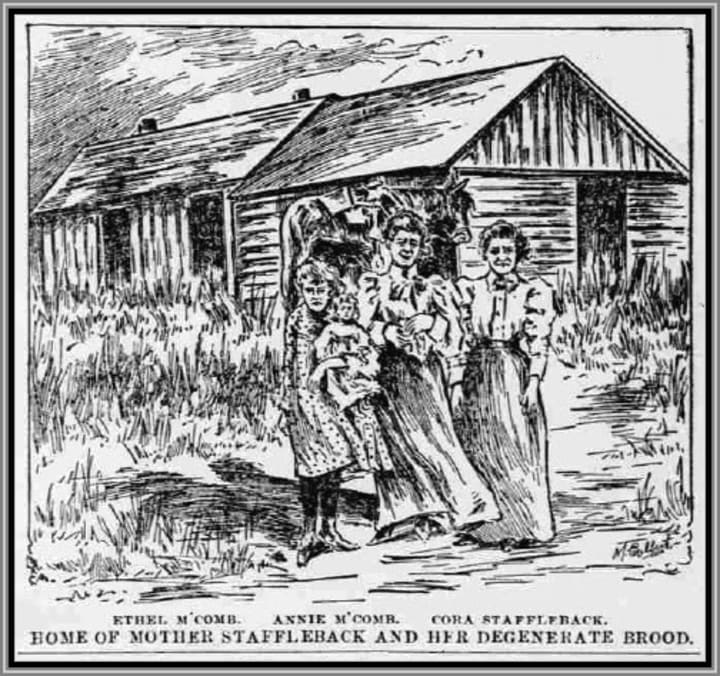

Remarkably, Kansas was the stalking ground of another murderous clan, the Stafflebecks. After divorcing their father, Nancy Stafflebeck moved with her children to Joplin, Missouri. Before long, her sons Ed, George, and Mike served time in the state prison for theft, and her daughters Emma and Louisa became prostitutes. In 1894, the family moved to Picker’s Point, a collection of ramshackle structures outside Galena, Kansas. They lived there with Mrs. Stafflebeck’s lover Charles Wilson, George Stafflebeck’s wife Cora, and two other women.

This mining region provided the Stafflebecks a convenient means to dispose of bodies. They lured victims to their four-room bordello home with the promise of illicit sexual activity. Once inside, they were robbed, murdered, and then thrown down one of the mine shafts dotting the countryside.

In July of 1897, a miner named Frank Galbraith came by the house to see Emma, but she was with another customer, so Nancy sent him away. He returned in the wee hours of the next morning and got into an altercation with Nancy, who refused to admit him. Ed ended up shooting Galbraith in the head and cutting his throat. The family then stripped the body, threw it down the mine shaft, and then Ed made everybody tamales. (You can’t make this stuff up.)

Another miner discovered Galbraith’s body in the mine shaft and reported it to the police, who conducted a raid on the bordello, arresting Nancy and her sons. Wilson managed to flee before the arrest.

“The one fact that a family of sons, together with their wives and their sisters, were practically partners with their gray-headed mother in a bawdy house of the very lowest type should condemn every one of them to the rope, were it not for the fact criminals are not hung in Kansas.” — Daily Globe, July 31, 1897

The other women turned state’s evidence. They told the court about other people the family killed, including an Italian peddler, an older man courting Nancy, a traveler, and two young women staying with the family. The exact number of their victims is unknown.

Nancy, age 65, was convicted and sentenced to 25 years in prison, where she died at age 81. The court convicted Ed and George of murder and sentenced them to life in prison. Mike also went to jail for numerous other offenses.

There have been several other killer families in both the United States and worldwide in more recent times. Are serial killers born or bred to kill? In the case of these families, it was probably a little of both.

About the Creator

Denise Shelton

Denise Shelton writes on a variety of topics and in several different genres. Frequent subjects include history, politics, and opinion. She gleefully writes poetry The New Yorker wouldn't dare publish.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.