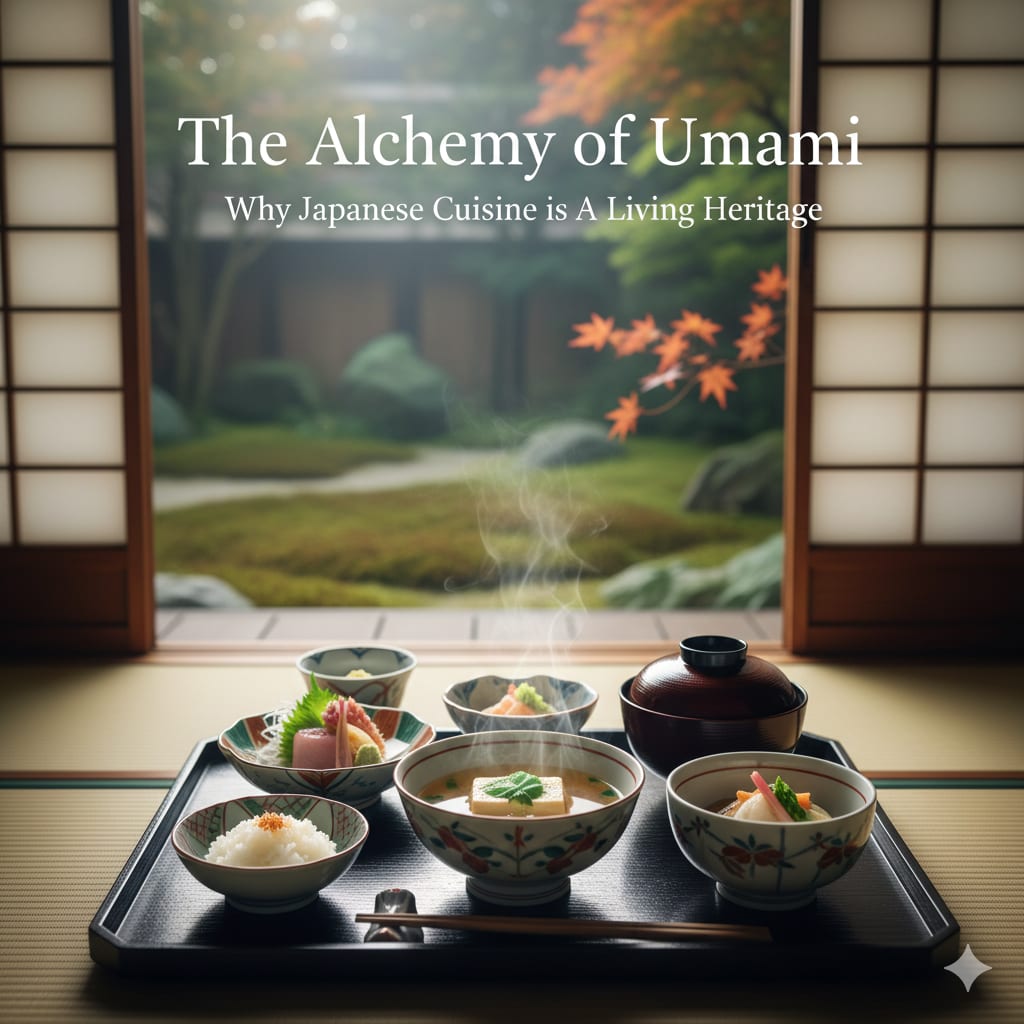

The Alchemy of Umami: Why Japanese Cuisine is a Living Heritage

Beyond Sushi and Ramen: Discovering the spiritual philosophy and 1,200 years of history behind 'Washoku'.

1. The Great Prohibition: 1,200 Years Without Meat

Most people looking at a modern bowl of Tonkotsu ramen or a plate of Wagyu steak would find it hard to believe that for over a millennium, Japan was essentially a vegetarian nation. In 675 AD, Emperor Tenmu, influenced by the Buddhist teachings of compassion and the Shinto ideals of purity, issued a decree that prohibited the consumption of beef, horse, dog, monkey, and chicken.

This was not a mere temporary trend; this ban remained the cultural and legal backbone of Japan for nearly 1,200 years until the Meiji Restoration in the late 19th century. However, human nature craves flavor. This forced abstinence became the mother of invention. The Japanese people became unparalleled masters of the sea and the soil. They turned to the soybean, transforming it into miso, shoyu (soy sauce), and tofu. They turned to the ocean, not just for fish, but for seaweed and crustaceans. Japanese cuisine, or Washoku, was born from a paradox: achieving infinite culinary richness within a world of strict limitations.

2. The Molecular Soul: The Discovery of Umami

While Western culinary traditions often rely on "addition"—adding fats, creams, and heavy sauces to build flavor—Japanese cooking relies on "extraction." At the heart of this extraction is Umami, the elusive fifth taste.

For centuries, Western science recognized only sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. But in 1908, a Japanese chemist named Kikunae Ikeda noticed a savory depth in his wife’s cucumber soup that couldn’t be explained by the traditional four. He traced this flavor to the kombu (kelp) used in the broth and identified the amino acid "glutamate."

This was the birth of Umami. In Japanese, it literally translates to "pleasant savory taste." When combined with Inosinate (found in dried bonito flakes), the two create a synergistic effect that amplifies flavor by eight times. This is the "Alchemy of Umami." It allows a simple dashi broth to possess a satisfying "meatiness" without a single gram of animal fat. It is a cuisine of the invisible, where the most profound flavors are often found in the clearest liquids.

3. Nature as the Executive Chef: The Rule of Five

Washoku is governed by a spiritual framework known as the "Rule of Five" (Go-shiki, Go-mi, Go-ho). A truly balanced Japanese meal should incorporate:

Five Colors: Red, yellow, green, black, and white.

Five Flavors: Sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami.

Five Methods: Raw, grilled, steamed, boiled, and fried.

This isn't just for aesthetics. By following these rules, a chef ensures that the meal is nutritionally complete and seasonally appropriate. It embodies the philosophy of Shun (旬)—eating ingredients at the absolute peak of their freshness. In the Japanese mindset, to eat a bamboo shoot in spring or a saury fish in autumn is to physically harmonize one’s body with the rhythm of the Earth. It is an act of mindfulness that acknowledges we are not separate from nature, but a part of it.

4. The UNESCO Recognition: A Living Spirit

In 2013, UNESCO added Washoku to its Intangible Cultural Heritage list. Crucially, they did not just protect the recipes; they protected the social practice.

Washoku is tied to the spirit of the Japanese New Year (Osechi), where each ingredient is a prayer: shrimp for long life, herring roe for fertility, and black beans for hard work. It is tied to the high lifespan of the Japanese people, who enjoy one of the lowest rates of heart disease and obesity in the industrialized world. But most importantly, it is tied to the word "Itadakimasu." Often translated simply as "Let’s eat," its true meaning is: "I humbly receive the life of this plant/animal." It is a profound acknowledgment of the cycle of life and death.

5. Conclusion: A Lesson for the Modern World

In our era of fast food and processed ingredients, Japanese cuisine stands as a silent protest. It teaches us that luxury is not found in expensive spices or oversized portions, but in the clarity of a single radish, the fermentation of a bean, and the gratitude in a single breath.

The alchemy of umami is not just a chemical reaction; it is a cultural one. It is the story of a people who looked at a barren plate and saw a garden. As you enjoy your next Japanese meal, look past the presentation. Taste the 1,200 years of history, the molecular science of the sea, and the quiet spirit of a heritage that is very much alive.

About the Creator

Takashi Nagaya

I want everyone to know about Japanese culture, history, food, anime, manga, etc.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.