A Century of Clues: The History of New York Times Crossword Culture

An in-depth exploration of how the New York Times crossword grew from a newspaper curiosity into a cultural institution that reflects a century of language, society, and collective challenge.

For many, solving a crossword puzzle is a quiet morning ritual, a mental stretch between coffee sips. Yet the story of the New York Times crossword is far more than a daily pastime—it is a century-long narrative woven into American culture, language, and collective cognition. From its humble beginnings to its digital transformation, the crossword has accumulated devoted solvers, landmark controversies, and an evolving identity that mirrors shifts in how we think, play, and connect.

Origins of a Grid: 1910s–1930s

The crossword puzzle as we know it today debuted in the New York World in 1913, invented by Arthur Wynne, a journalist from Liverpool. Its diamond-shaped grid and interlocking words captured readers’ imagination immediately; its popularity prompted imitators in newspapers across the country. But it wasn’t until the New York Times introduced its own crossword in 1942 that the format began its ascent into cultural prominence.

At the time, the Times was cautious. Editors worried that crosswords were frivolous, unworthy of the paper’s serious reputation. But circulation numbers told another story: demand was strong, and by the 1950s the crossword had become an institution within the paper, a daily fixture that straddled entertainment and intellectual pursuit.

The Puzzle as Practice: Growth Through the Mid-Century

Across the decades, the puzzle evolved alongside American life. Solvers were once a niche community, often connected through local clubs and word-of-mouth gatherings. But with regular publication, New York Times puzzles became almost a rite of passage for literate puzzle enthusiasts. What began as a print diversion became a measure of linguistic acuity—a challenge to be conquered, often discussed over breakfasts or exchanged between friends.

As the puzzle developed, constructors also began to leave their mark. Names like Will Weng, Eugene T. Maleska, and later Will Shortz shaped editorial voices, each influencing the tone, difficulty, and cultural references embedded in the clues.

“A good crossword puzzle is a work of art,” Will Shortz once said. “It’s not just words—it’s the tension between knowledge and discovery.”

— Will Shortz, Crossword Editor

From Ink to Interface: Digital Transformation

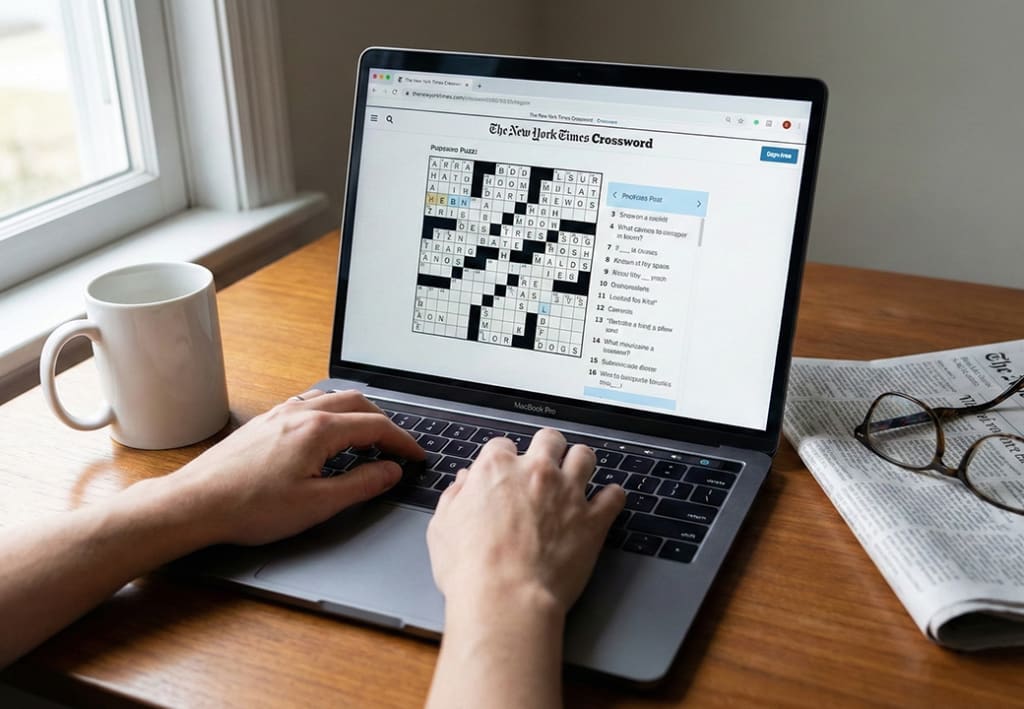

The 21st century brought seismic shifts to how people engage with media. The rise of smartphones, tablets, and web platforms changed not only access but the very culture of puzzle solving. No longer confined to a Sunday newspaper section, crossword fans could log in from anywhere and tackle grids on demand.

Digital platforms introduced conveniences—timers, hints, and the ability to check answers instantly—but also sparked debates among purists. For many longtime solvers, the tactile pleasure of pen on paper held a unique charm that scrolling screens could not replicate. For new generations, the interactive layout brought excitement and community, especially with features that allowed sharing results and competing with friends.

In the digital age, the archive of past puzzles became a resource for study and nostalgia. Enthusiasts often discuss patterns, favorite themes, and memorable clues, creating fan sites, discussion boards, and walkthroughs of challenging puzzles. One resource frequently referenced by solvers is https://dazepuzzle.com/ny-times-crossword-answers/, which offers guidance—though not without controversy—on answers and strategies.

The Culture of Difficulty: Monday to Saturday, Then Beyond

One of the New York Times crossword’s defining characteristics is its graduated difficulty. Mondays are accessible and gentle, building confidence; by Friday and Saturday, the grid becomes a formidable foe of obscure references and tricky wordplay. Sundays, while larger in size, tend to present a mid-level challenge balanced between length and complexity.

This structure creates a shared rhythm for solvers. Social media is replete with posts like “Crushed today’s Saturday puzzle!” or “Struggling with Thursday’s grid,” turning what might be a solitary task into a collective experience. For many, the weekly climb in challenge becomes part of the ritual itself.

“Crosswords are less about what you know and more about how you think.”

— Puzzle Analyst, Chronicle of Word Games

Community and Competition

Perhaps more than any other element, the community that surrounds the crossword distinguishes it. Crossword clubs, university puzzle groups, and international forums bring together people from diverse backgrounds with a shared love for words and logic. The culture spans generations: parents who solved crosswords in print introducing their children to digital grids.

Competitions also emerged as hotspots of communal appreciation. Events like the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament draw both elite solvers and casual devotees, bridging skill levels in a celebration of linguistic intellect. These tournaments underscore how a daily habit can blossom into a shared passion with recognizable stars and dedicated followings.

Puzzles as Cultural Mirror

Crosswords do more than test vocabulary—they reflect the time in which they are made. As language evolves, so too do clues and answers; slang, pop culture, and global awareness find their way into grids. This evolution sometimes sparks debate—about inclusivity, relevance, and representation. What once might have been esoteric references to classical literature now mingle with nods to contemporary music, international cuisine, or viral phenomena.

Such adaptations reveal not only changing language but shifting societal values. Constructing a puzzle becomes a balancing act: honoring tradition while making space for innovation and broader cultural touchpoints.

The Future of the Grid

Looking forward, the future of the New York Times crossword appears vibrant and multifaceted. Technology continues to expand possibilities: interactive formats, adaptive difficulty, and AI-assisted puzzles all blur the boundaries between static challenges and dynamic play. At the same time, community engagement grows stronger through shared solve posts, digital meetups, and collaborative puzzle creation.

Yet at the heart of this evolution remains the enduring appeal of the crossword: the pleasure of cracking a clue, the “aha!” moment when a pattern emerges, and the sense of connection to a tradition that has spanned generations.

“Crosswords aren’t just entertainment—they are a way of thinking, a habit of discovery that keeps our minds curious.”

— Cultural Commentator on Language and Games

Conclusion: A Puzzle That Tells a Story

The New York Times crossword is more than a daily exercise—it is a cultural artifact that captures how we interact with language, challenge, and one another. From printed squares in a 20th-century newspaper to globally accessible digital grids, the puzzle’s journey mirrors changes in media, cognition, and community. As long as people delight in words and the thrill of discovery, the crossword will remain a living tradition—a century of clues with much more still to explore.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.