Latest Stories

Most recently published stories in History.

She Chose to Be Sicilian. Others Died for Being Sicilian.. Content Warning.

Copenhagen, 1925. There’s a young woman at the harbor, watching the Little Mermaid disappear into the fog. Her bags are at her feet. She’s got a ticket tucked in her coat. Tomorrow, she’s sailing south.

By Olga Angelucciabout an hour ago in History

The Muslim Math a Christian Emperor Refused to Reject

1225, Southern Italy. A Christian emperor sits across from a mathematician trained in the Islamic world. He asks a question about numbers. What happens in the next hour will quietly reshape Europe—though no one in that room realizes it yet.

By Olga Angelucciabout an hour ago in History

Outsiders Who Took Over Southern Italy—and Wrote Themselves In

By the early 800s, southern Italy was a mess. You had Lombard princes in one corner, Byzantine governors in another. Nobody was strong enough to call the shots, but nobody wanted to back down either. Power shifted all the time. Cities flipped sides. Loyalty was just another thing you could bargain with. The only thing holding the place together was plain exhaustion.

By Olga Angelucciabout an hour ago in History

Sicily Didn’t Fall Because of Love

Syracuse, early ninth century. Euphemius lingered by the water, probably longer than was wise. The harbor felt hollow, almost staged—too quiet, like the world was holding its breath. Even the smallest sounds—waves slapping wood, a foot scuffing stone, someone clearing their throat—bounced around, too loud. The soldiers behind him shifted and fidgeted, but nobody wanted to break the silence.

By Olga Angelucciabout an hour ago in History

Empire in Ashes

In late summer of the year 476, the Western Roman Empire was already a shadow of its former self, but its final hours still carried the weight of a thousand years of power. Rome no longer ruled the Mediterranean world; its emperors were puppets, its armies filled with foreign mercenaries, its treasury nearly empty. In Ravenna, the imperial capital, the teenage emperor Romulus Augustulus waited behind palace walls while events moved beyond his control. Real authority rested with Orestes, his father and commander of the army, who had seized power only a year earlier. But the soldiers who kept the empire standing had grown restless. They were foederati—Germanic troops who fought for Rome in exchange for land—and they now demanded what had long been promised. When Orestes refused, their leader, a seasoned warrior named Odoacer, turned against him. Within days, Odoacer’s forces marched across northern Italy, crushing resistance with alarming ease. Orestes was captured near Piacenza and executed, and the road to Ravenna lay open. As the final seventy-two hours began, Ravenna was tense but strangely quiet. The once-mighty empire had no legions left to defend its emperor, only thin walls and fading prestige. Odoacer’s army surrounded the city, not with the fury of a sack, but with the confidence of inevitability. Inside the palace, Romulus Augustulus—named after Rome’s legendary founder and its first emperor—stood as a tragic symbol of decline. He was young, inexperienced, and powerless, ruling an empire that existed more in memory than in reality. There was no dramatic last stand, no desperate counterattack. Negotiations replaced battles, and survival replaced pride. When Odoacer entered Ravenna, he did not burn it. He deposed the boy emperor peacefully, an act that was both merciful and final. Romulus was spared, granted a pension, and sent into exile, likely to live out his life in obscurity while history moved on without him. In the final hours, the symbols of empire were quietly dismantled. The imperial regalia—the crown, the purple robes, the insignia of supreme authority—were gathered and prepared for a journey east. Odoacer made a calculated decision that marked the true end of Western Roman rule: he did not name a new emperor. Instead, he sent the imperial insignia to Constantinople, acknowledging the Eastern Roman Emperor, Zeno, as the sole ruler of the Roman world. The message was clear and unprecedented. The West no longer needed its own emperor. What had once been the heart of a global empire was now a kingdom ruled by a barbarian king in Roman clothing. As the seventy-two hours closed, no single moment announced the fall. There were no collapsing walls or burning palaces, only the quiet disappearance of an institution that had shaped Europe, North Africa, and the Mediterranean for centuries. The Roman Senate still existed. Roman laws were still enforced. Cities still stood. But the idea of a Western Roman Emperor—an unbroken line stretching back to Augustus—was gone. The world did not end in 476, but it undeniably changed. Power fragmented, trade routes weakened, and Western Europe slowly entered a new era of competing kingdoms and shifting identities. Rome, once the ruler of the known world, became a memory, a symbol, and eventually a legend. The final seventy-two hours of the Western Roman Empire were not marked by chaos, but by quiet acceptance. Its fall was not a sudden collapse, but the last breath of a long decline. Yet even in ashes, Rome endured. Its language, laws, architecture, and ideas survived its emperors, shaping civilizations long after the crown was laid down. The empire died not with a roar, but with a whisper—leaving behind a legacy that still defines the modern world.

By Talhamuhammadabout 4 hours ago in History

Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series: Oligarchy’s Deep Roots in the Agriculture Industry

When you think of elite influence, your mind might jump to energy markets or tech monopolies. But few realise how deeply entrenched oligarchic wealth has become in agriculture—a sector traditionally seen as humble, grounded, and vital. In this edition of the Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series, we explore how agricultural assets have quietly become strategic holdings for the ultra-wealthy.

By Stanislav Kondrashov about 4 hours ago in History

The Demanding Factors That Created Alexander the Great’s Path to Victory

1. The Foundation Laid by Philip II of Macedon One of the most important factors behind Alexander’s victories was the groundwork laid by his father, King Philip II of Macedon. Philip transformed Macedonia from a weak kingdom into a dominant military power. He reorganized the army, introduced the Macedonian phalanx, and armed soldiers with the long sarissa spear, which gave them a decisive advantage over traditional Greek hoplites.

By Say the truth about 9 hours ago in History

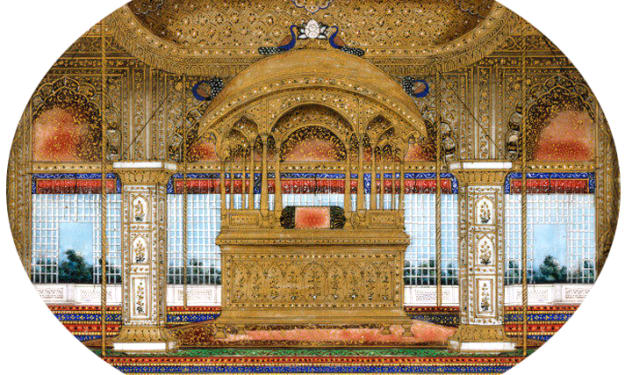

The Net Worth of the Peacock Throne: Valuing the World’s Most Luxurious Lost Treasure. AI-Generated.

What Was the Peacock Throne? The Peacock Throne was completed around 1635 CE and placed in the Mughal imperial court at Delhi. It was constructed almost entirely of solid gold and covered with some of the most valuable gemstones known to humanity. At its center stood two jewel-encrusted golden peacocks, their tails raised high and spread wide, symbolizing royalty, immortality, and divine authority.

By Say the truth about 10 hours ago in History