A System That Doesn’t Know the Difference Between Guilt and Vulnerability

A young man with the mind of a child was executed by a system that mistook compliance for guilt. Joe Arridy’s story exposes how justice can function perfectly on paper while failing catastrophically in practice. This is not just about one wrongful conviction, it is about the quiet design flaws that make such tragedies possible.

Joe Arridy did not understand the word execution.

He understood trains.

He understood ice cream.

He understood kindness.

But he did not understand the system that would kill him.

And that is the point.

We like to believe systems are rational.

Courts. Prisons. Schools. Institutions.

They are supposed to organize chaos. Deliver fairness. Protect the innocent. Punish the guilty.

They promise order.

But sometimes the failure of a system does not look like collapse.

It looks like paperwork filed correctly.

A confession signed.

A jury convinced.

A sentence carried out.

Everything functioning.

Everything wrong.

...

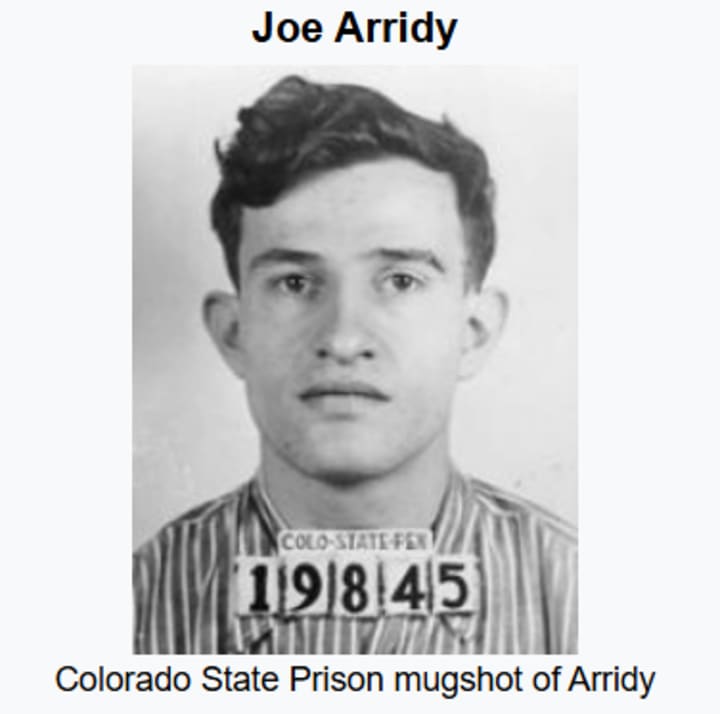

Joe Arridy was born in 1915 with severe intellectual disabilities. His IQ was measured at 46. He did not speak until he was five. School rejected him after a single year. The world decided early that he did not fit its design.

There was no safety net waiting for him.

Only institutions.

Institutions promise care.

What they often deliver is containment.

Joe was sent to a state institution that claimed to protect vulnerable people. Instead, he was bullied, isolated, and misunderstood. By adulthood, most of his life had been lived under supervision — not protection, but control.

Before he was accused of a crime, he had already been processed by systems that did not know what to do with him.

He did not fail them.

They were never built for him.

...

In 1936, a young girl in Pueblo, Colorado was raped and murdered.

The town wanted justice.

The police wanted a suspect.

The system wanted closure.

Joe was traveling by train during the Great Depression when he was arrested. There was no physical evidence tying him to the crime.

But there was something the system values more than evidence.

A confession.

His confession was inconsistent. It shifted. It contained details fed to him. Investigators later admitted he was highly suggestible. He wanted to please authority figures. He repeated what he was told.

He did not understand the gravity of what he was agreeing to.

But the system did not measure comprehension.

It measured compliance.

And compliance was enough.

He was convicted.

...

Here is the quiet violence of a system that isn’t working:

It does not require malice.

It does not require hatred.

It does not even require certainty.

It only requires momentum.

Police do their job.

Prosecutors do theirs.

Jurors follow instructions.

Judges pronounce sentence.

No one person has to be cruel.

The cruelty is distributed.

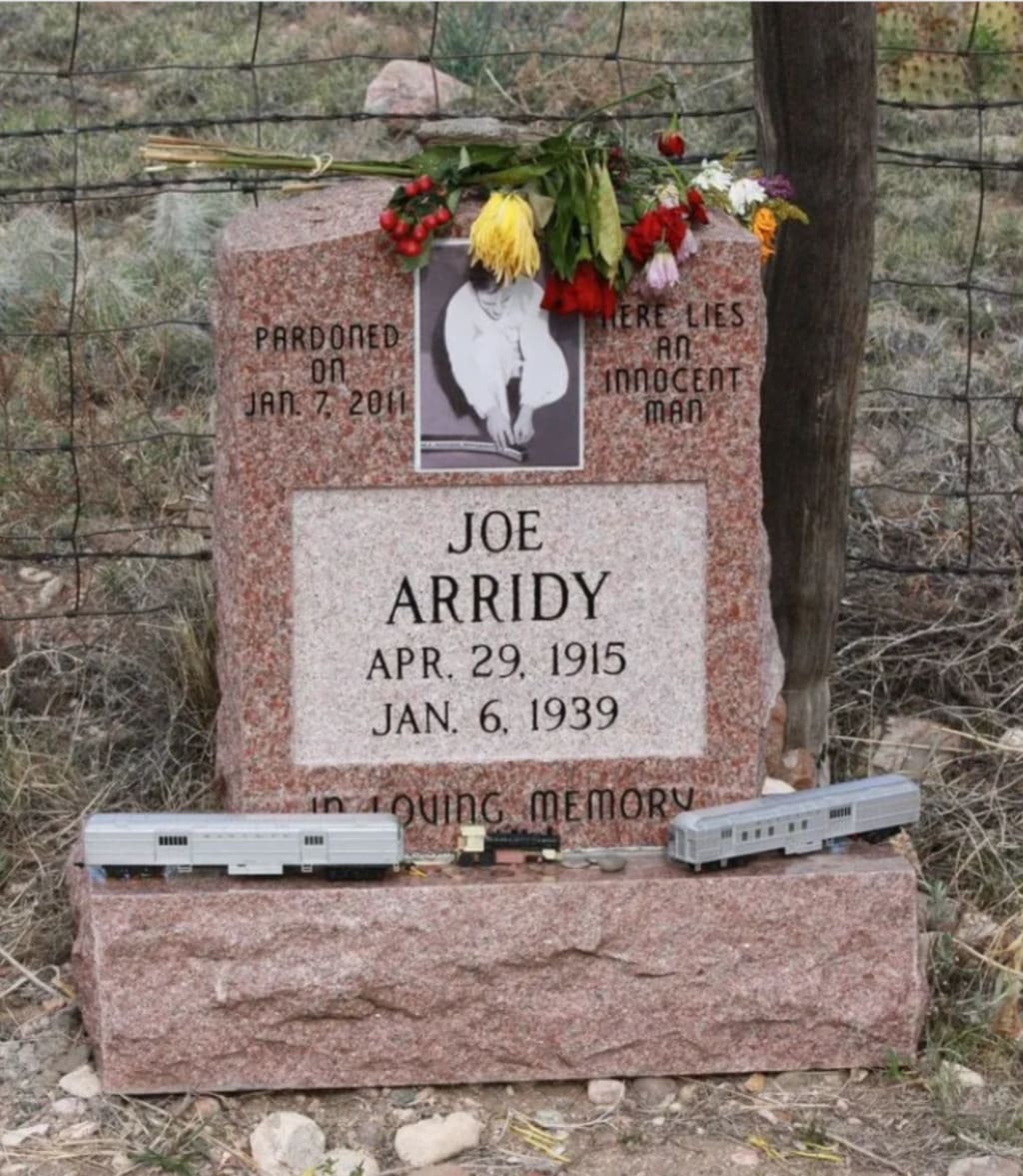

Joe Arridy was executed in 1939.

He was 23 years old.

...

Decades later, in 2011, he was posthumously exonerated. Evidence pointed to another man. Officials acknowledged what should have been obvious: Joe did not have the capacity to understand what he was accused of, let alone orchestrate the crime described.

Justice arrived but it arrived too late to matter.

The system corrected itself — symbolically.

Joe remained dead.

Even in prison, Joe held onto something the system could not extract from him: joy.

He loved a toy train. He played with it in his cell, escaping into a world that made sense to him. Guards described him as cheerful. Childlike. Gentle.

...

On the day of his execution, he gave the toy to another prisoner.

For his final meal, he asked for ice cream.

He asked that it be saved for later.

He did not understand that there would be no later.

Let that settle.

A man executed by the state did not know he was being executed.

And yet the system insists it worked.

The challenge is not simply that an innocent man died.

The challenge is that the system was designed in a way that made his death possible.

It valued confession over comprehension.

Procedure over protection.

Closure over caution.

...

Joe Arridy was not overlooked by accident.

He was processed exactly as the structure allowed.

And that should disturb us more than any single mistake.

We often imagine injustice as dramatic involving; corrupt officials, forged evidence, intentional evil.

But most systemic failure looks quieter.

It looks like:

• A vulnerable person being questioned without safeguards.

• A jury equating disability with guilt.

• A public too desperate for answers to tolerate uncertainty.

It looks like a system optimized for efficiency, not empathy.

Joe was not dangerous.

He was different.

And in systems built around speed, pressure, and public reassurance, difference becomes risk.

Not because it should but because it is inconvenient.

Ask yourself something uncomfortable:

If Joe Arridy were alive today, would we be certain this could not happen again?

...

We have improved procedures.

We have disability advocacy.

We have reforms.

But we also still have:

False confessions.

Overworked public defenders.

Pressure to close cases quickly.

A public appetite for swift justice.

We still reward certainty over humility.

We still confuse authority with truth.

We still trust systems more than we question them.

Joe’s story is not just about the death penalty.

It is about design.

Who do our systems protect instinctively?

Who must fight to be understood?

Who is believed?

Who is processed?

...

Every system shapes someone.

Every system overlooks someone.

And the people most overlooked are rarely the powerful, aren't they?

They are the ones who struggle to articulate themselves.

The ones who appear “different.”

The ones who cannot advocate loudly.

The ones who would ask to save their ice cream for later.

The measure of a society is not how efficiently it convicts.

It is how carefully it listens.

Joe Arridy’s life asks us to confront something unsettling:

What if injustice does not require monsters?

What if it only requires indifference?

What if the system isn’t broken in obvious ways — but misaligned in quiet, deadly ones?

So I want to ask you — not rhetorically, but honestly:

When was the last time you questioned a system you benefit from?

When was the last time you considered who it leaves behind?

If someone like Joe stood in front of us today; confused, compliant, eager to please — would we slow down?

Or would we move forward, confident the process will sort itself out?

...

Justice is not just about verdicts.

It is about understanding.

Joe Arridy never understood what was happening to him.

The real question is:

Do we?

Really?

About the Creator

Lori A. A.

Teacher. Writer. Tech Enthusiast.

I write stories, reflections, and insights from a life lived curiously; sharing the lessons, the chaos, and the light in between.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.