“I’m Proud to Be an American” is Antichristian Nationalism

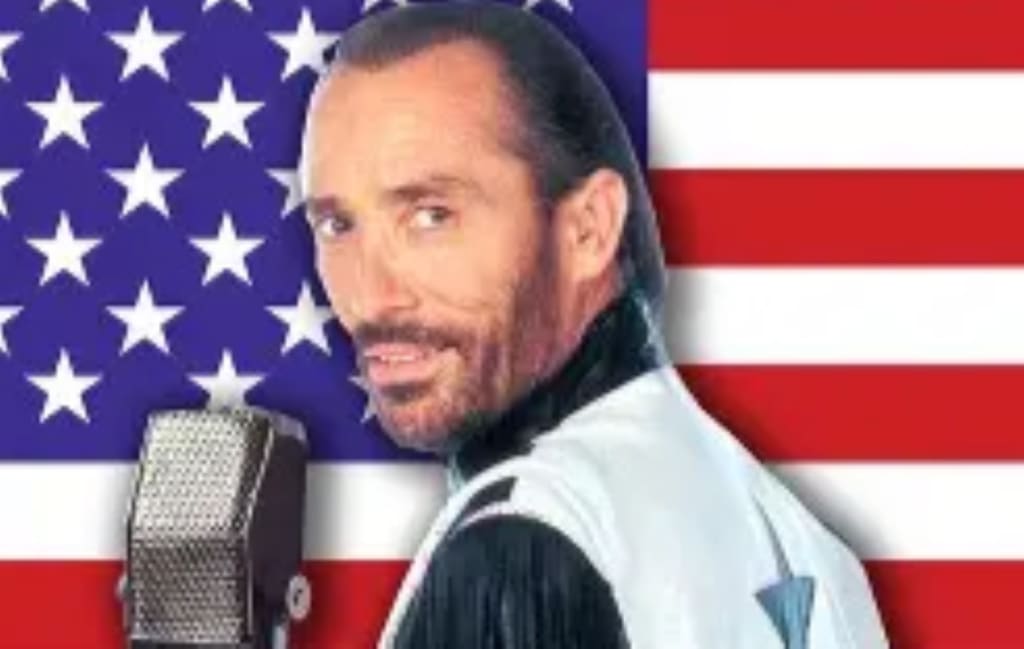

I have always felt a little cringey whenever I hear Lee Greenwood belting out "God Bless the U.S.A." out on the radio or at events. Although it strokes the ego of a large section of the U.S.A. populance, it is NOT a Christian song, and it doesn't manifest or support God's values.

Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the U.S.A.”—popularly known by its refrain “I’m Proud to Be an American”—has become one of the most enduring patriotic anthems in the United States. Released in 1984, it surged in popularity during the Gulf War and again after the September 11 attacks. It is performed at political rallies, military ceremonies, and civic events, often treated as a quasi-sacred hymn of national identity.

Yet when examined through the lens of Christian theology, Greenwood’s anthem raises troubling questions. Christianity proclaims a universal gospel, transcending nations and cultures. The kingdom of God is not bound to any political entity. To sacralize America as uniquely blessed risks idolatry, distorting the gospel into nationalism. This essay argues that “God Bless the U.S.A.” is antichristian in its implications, because it elevates the United States as “God’s country,” conflating patriotism with divine favor.

Historical Background of the Song

Greenwood wrote “God Bless the U.S.A.” during the Reagan era, a time of resurgent patriotism. The song’s lyrics celebrate American freedom, honor military sacrifice, and invoke God’s blessing on the nation. Its chorus—“And I’m proud to be an American, where at least I know I’m free”—became a rallying cry for unity.

The song’s cultural power lies in its ability to sacralize national identity. By invoking God’s blessing, it transforms patriotism into civil religion. Scholars such as Robert Bellah have described American civil religion as a set of beliefs and rituals that sacralize the nation, blending political identity with religious language. Greenwood’s anthem is a prime example.

Theological Critique

1. God’s Kingdom Transcends Nations

Christian scripture insists that God’s kingdom is not of this world (John 18:36). Jesus rejects political messianism, proclaiming a kingdom that transcends borders. Greenwood’s anthem, however, implies that America is uniquely blessed, conflating divine favor with national identity.

2. Universalism of the Gospel

Paul declares: “There is neither Jew nor Greek…for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). Christianity abolishes divisions of ethnicity and nationality. To elevate America as “the best” contradicts this universality, suggesting that God favors one nation above others.

3. Idolatry of Nation

Idolatry is placing anything above God. When patriotism becomes sacralized, the nation itself becomes an idol. Greenwood’s lyrics risk turning America into a false god, demanding devotion that should belong to Christ alone.

4. Misplaced Freedom

The song celebrates freedom as America’s defining gift. Yet Christian theology teaches that true freedom is found in Christ, not in political systems (Romans 6:22). To equate American freedom with divine blessing misplaces the source of salvation.

Theological Counterpoints

Biblical Universalism

Scripture repeatedly emphasizes God’s concern for all nations. The Great Commission (Matthew 28:19) commands disciples to make disciples of all nations. Revelation envisions a multitude from every tribe and tongue worshiping God (Revelation 7:9). Christianity is global, not national.

The Danger of Idolatry

The prophets repeatedly warn against idolatry. To sacralize the nation is to create a false god. Greenwood’s anthem risks turning America into an idol, demanding devotion that should belong to God alone.

True Freedom in Christ

Paul teaches that freedom is found in Christ, not in political systems. “For freedom Christ has set us free” (Galatians 5:1). To equate American freedom with divine blessing misplaces the source of salvation.

Contemporary Relevance

Global Christianity

Christianity is now a global faith, with the majority of believers living outside the West. Elevating America as uniquely blessed ignores the vitality of Christianity in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Greenwood’s lyrics distort the reality of God’s work worldwide.

Social Justice and Universalism

Christianity calls believers to justice and compassion for all people. Nationalism that elevates America above others contradicts this call. Greenwood’s anthem risks fostering exclusion rather than inclusion.

The Church’s Witness

The church’s witness is compromised when it conflates patriotism with faith. To sing Greenwood’s anthem as though it were a hymn risks distorting the gospel, turning Christianity into civil religion.

Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the U.S.A.” is celebrated as a patriotic anthem, but when measured against Christian theology, it is antichristian in its implications. By sacralizing America as uniquely blessed, it risks idolatry, distorts the gospel’s universality, and feeds into Christian nationalism.

Christianity insists that God has not singled out the United States as “his country.” The kingdom of God transcends borders, calling believers to place their ultimate loyalty not in nation, but in Christ. To conflate patriotism with divine favor is to betray the gospel’s radical universality.

Line‑by‑Line Analysis of God Bless the U.S.A.

Opening Verse: “If tomorrow all the things were gone I’d worked for all my life…”

Greenwood begins with a hypothetical loss of material possessions. The sentiment is deeply American: identity tied to property, labor, and individual achievement. From a Christian perspective, however, this emphasis on possessions contrasts with Jesus’ teaching in Matthew 6:19–21, where believers are urged not to store up treasures on earth but in heaven. The lyric implicitly equates human worth with material accumulation, rather than spiritual inheritance.

“And I had to start again with just my children and my wife…”

Here Greenwood grounds identity in family. While family is a biblical value, Christianity insists that discipleship sometimes requires leaving family ties behind (Luke 14:26). The lyric elevates family as the ultimate anchor, whereas Christian theology places Christ as the center of identity.

“I’d thank my lucky stars to be living here today…”

This phrase invokes “lucky stars,” a secular idiom, rather than gratitude to God. Theologically, Christians are called to thank God for life and salvation, not chance or national circumstance. The lyric subtly shifts devotion from divine providence to national fortune.

Chorus: “And I’m proud to be an American, where at least I know I’m free…”

This refrain is the heart of the anthem. Pride in national identity is celebrated as the highest good. Yet Christian theology warns against pride as a sin (Proverbs 16:18). Moreover, the freedom Greenwood extols is political freedom, whereas Paul insists that true freedom is found only in Christ (Galatians 5:1). The lyric conflates civic liberty with spiritual liberation, misplacing the source of salvation.

“And I won’t forget the men who died, who gave that right to me…”

This line honors military sacrifice. While respect for sacrifice is noble, Christianity teaches that ultimate freedom was purchased by Christ’s death, not by soldiers. Elevating military sacrifice as salvific risks idolatry, replacing the cross with the battlefield.

“And I’d gladly stand up next to you and defend her still today…”

Here Greenwood pledges loyalty to the nation, equating patriotism with moral duty. Yet Jesus teaches that loyalty belongs to God’s kingdom above all (Matthew 6:33). The lyric suggests that defending America is the highest calling, overshadowing the Christian vocation of discipleship and service to all nations.

“’Cause there ain’t no doubt I love this land, God bless the U.S.A.”

This climactic line fuses love of land with divine blessing. Theologically, God’s blessing is not tied to geography. Christianity insists that God’s covenant is fulfilled in Christ, not in any nation-state. To claim divine blessing uniquely for America risks heresy, echoing Old Testament language of Israel as chosen people but misapplying it to a modern nation.

Second Verse: “From the lakes of Minnesota to the hills of Tennessee…”

Greenwood lists American geography, sacralizing the land itself. This echoes biblical psalms that praise God for creation, but here the praise is directed toward the nation rather than the Creator. The lyric risks turning geography into an idol, elevating national terrain above universal creation.

“Across the plains of Texas, from sea to shining sea…”

This phrase echoes America the Beautiful. It reinforces the idea of America as uniquely blessed land. Yet Christian theology insists that all creation is God’s, not one nation’s possession. The lyric narrows divine blessing to national borders, contradicting the universality of God’s reign.

“From Detroit down to Houston, and New York to L.A…”

By naming cities, Greenwood emphasizes industrial and cultural centers. This reflects pride in economic and cultural power. Yet scripture warns against boasting in human achievement (Jeremiah 9:23–24). The lyric equates divine blessing with national prosperity, misplacing the source of true glory.

“Well there’s pride in every American heart, and it’s time we stand and say…”

This line universalizes national pride, suggesting that all Americans share devotion to the nation. Yet Christianity insists that devotion belongs to God alone. To equate national pride with moral duty risks idolatry, turning patriotism into a false religion.

Repeated Chorus

The repetition reinforces the anthem’s central message: pride in America, gratitude for military sacrifice, and invocation of God’s blessing. Theologically, repetition functions like liturgy, embedding civil religion into cultural consciousness. Greenwood’s chorus becomes a hymn of nationalism, rivaling Christian worship.

Theological and Cultural Case Studies

Case Study 1: Civil Religion in America

Robert Bellah’s classic essay “Civil Religion in America” (1967) describes how American political life has developed its own religious dimension. Presidential speeches invoke God, national holidays function as sacred rituals, and patriotic songs serve as hymns. Greenwood’s anthem fits squarely within this tradition, functioning as a liturgical expression of civil religion.

Case Study 2: Post-9/11 Patriotism

After the September 11 attacks, “God Bless the U.S.A.” surged in popularity. It was performed at memorials, rallies, and sporting events. The song’s invocation of God’s blessing on America became a way of sacralizing national grief and anger. Yet this conflation of divine favor with national identity risked turning Christianity into a tool of nationalism, rather than a universal faith.

Case Study 3: Christian Nationalism

Christian nationalism is the belief that America has a special covenant with God. Scholars such as Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry have documented how Christian nationalism distorts the gospel, turning Christianity into a political ideology. Greenwood’s anthem feeds into this ideology, suggesting that America is uniquely blessed by God.

Case Study 4: Civil Religion as Liturgy

Greenwood’s anthem functions like a hymn in American civil religion. Its repetition, invocation of God, and sacralization of land mirror religious liturgy. Scholars note that patriotic songs often replace hymns in public ceremonies, blurring the line between worship of God and worship of nation.

These passages directly contradict Greenwood’s sacralization of America.

- Galatians 3:28: All are one in Christ, transcending nationality.

- John 18:36: Christ’s kingdom is not of this world.

- Matthew 28:19: The gospel is for all nations, not one.

- Revelation 7:9: A multitude from every tribe and tongue worships God.

Contemporary Relevance

Greenwood’s anthem continues to be performed at political rallies, military ceremonies, and civic events. Its popularity reflects the enduring power of civil religion in America. Yet its theological implications remain troubling. By sacralizing America as uniquely blessed, it distorts Christianity’s universal gospel, risks idolatry, and feeds into Christian nationalism.

Conclusion

Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the U.S.A.” is celebrated as a patriotic anthem, but when analyzed line by line, its theological problems become clear. Each lyric elevates America as uniquely blessed, conflates political freedom with spiritual liberation, and risks turning patriotism into idolatry. Christianity insists that God has not singled out the United States as “his country.” The kingdom of God transcends borders, calling believers to place their ultimate loyalty not in nation, but in Christ.

To sing Greenwood’s anthem as though it were a hymn is to betray the gospel’s radical universality. The church must resist civil religion and proclaim the true freedom found only in Christ.

References

- Bellah, Robert N. Civil Religion in America. Daedalus, 1967.

- Greenwood, Lee. God Bless the U.S.A. (1984).

- Whitehead, Andrew L., and Samuel L. Perry. Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States. Oxford University Press, 2020.

- The Holy Bible: Galatians 3:28; John 18:36; Romans 6:22; Matthew 28:19; Revelation 7:9.

- God Bless the U.S.A. – Wikipedia.

- Fox News interview with Lee Greenwood on the legacy of God Bless the U.S.A.

-

About the Creator

Julie O'Hara - Author, Poet and Spiritual Warrior

Thank you for reading my work. Feel free to contact me with your thoughts or if you want to chat. [email protected]

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.