APRIL 20, 1999 The Day I Became a Mother in a Different America

The Day I Became a Mother in a Different America

APRIL 20, 1999

The Day I Became a Mother in a Different America

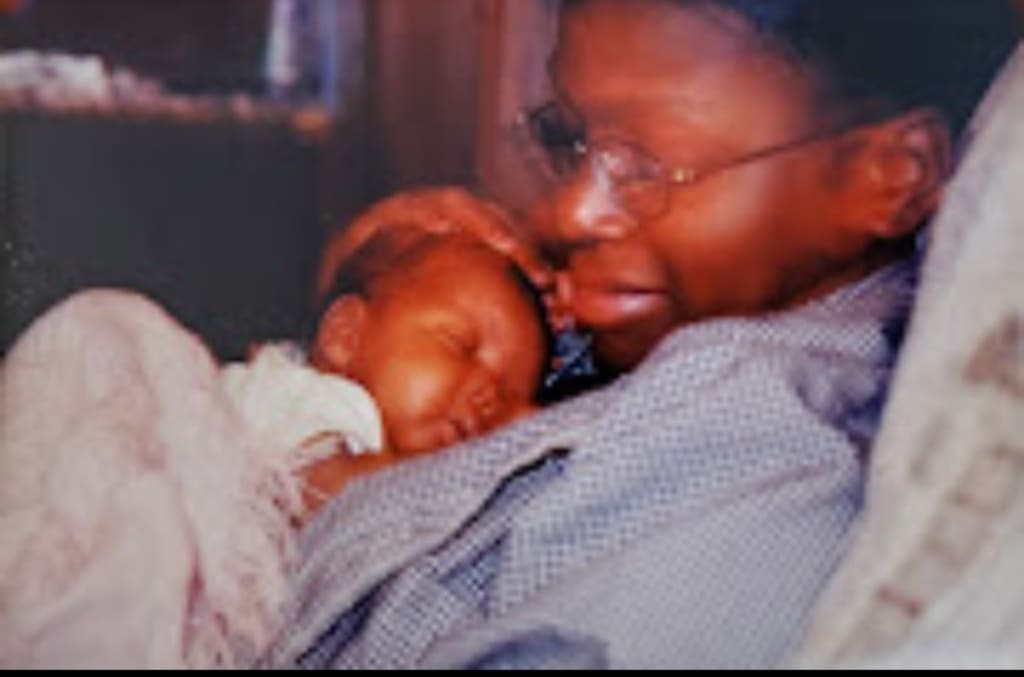

On April 19, 1999, I gave birth to my daughter.

I was nineteen years old.

Nineteen and overwhelmed in the normal ways — diapers, feeding schedules, whether she was latching correctly, whether I was holding her right. I was scared in the way new mothers are supposed to be scared. Scared about sleep. Scared about money. Scared about whether love would be enough.

Less than twenty-four hours later, I was sitting up in a hospital bed, sore, exhausted, holding a one-day-old baby, when the television mounted high in the corner of the room started showing smoke.

Teenagers running.

Police with rifles.

News anchors speaking in that strained, disbelieving tone that says something irreversible is happening.

April 20, 1999.

Columbine High School.

That was the moment motherhood changed shape for me.

Not because it was the first school shooting in American history.

But because it was the first one that landed directly in my body as a mother.

I remember looking down at my daughter’s face — perfect, quiet, unaware — and thinking:

I just brought a child into a world where school is not automatically safe.

And that thought never left.

The Names That Made It Real

Thirteen people were killed at Columbine:

Cassie Bernall, 17

Steven Curnow, 14

Corey DePooter, 17

Kelly Fleming, 16

Matthew Kechter, 16

Daniel Mauser, 15

Rachel Scott, 17

Isaiah Shoels, 18

John Tomlin, 16

Lauren Townsend, 18

Kyle Velasquez, 16

William “Dave” Sanders, 47

They were not statistics.

They were students who had lockers, homework, crushes, inside jokes. A teacher who tried to protect children.

I didn’t know them personally.

But I knew their mothers existed.

And suddenly I was one of them — a woman whose entire nervous system now lived outside her own body.

Psychologists call what happened next vicarious trauma — absorbing trauma through exposure, even from a distance.

I didn’t have that language then.

I just knew I had been changed.

The Ban That Was Already in Place

Here’s something people forget.

When Columbine happened, the Federal Assault Weapons Ban of 1994 was already active. It restricted certain semi-automatic weapons and high-capacity magazines. It was set to expire after ten years unless Congress renewed it.

In 2004, it expired.

It was not renewed.

Studies later published in medical journals suggested that mass shooting fatalities were lower during the ban years compared to the decade after it expired. The debate around causation continues.

But the timeline is factual.

1994–2004: Ban active.

2004: Ban expires.

Post-2004: High-casualty mass shootings increase in frequency and scale.

While politicians debated, parents absorbed fear in real time.

In 2004, the same year the ban expired, I gave birth to my son.

Now I had two.

The Birth of Hypervigilance

People joke about helicopter parents.

I became one on April 20, 1999.

Hypervigilance is a clinical term for constantly scanning for danger. Chronic anticipatory anxiety is the expectation that something bad will happen, even when everything is quiet.

That became my baseline.

I created safety systems.

If I texted my daughter and something felt off, I would ask her a question only she would know how to answer. A code. A verification.

When my son started school, I studied layouts. I noticed exits. I evaluated drop-off procedures.

My son never rode a school bus.

Not once.

From preschool until his graduation in 2020, I dropped him off and picked him up every single day.

That wasn’t convenience.

That was my nervous system trying to negotiate with fear.

2012 — When It Broke Open Again

December 14, 2012.

Sandy Hook Elementary School.

Twenty children. Six educators.

The children were six and seven years old:

Charlotte Bacon

Daniel Barden

Olivia Engel

Josephine Gay

Ana Márquez-Greene

Dylan Hockley

Madeleine Hsu

Catherine Hubbard

Chase Kowalski

Jesse Lewis

James Mattioli

Grace McDonnell

Emilie Parker

Jack Pinto

Noah Pozner

Caroline Previdi

Jessica Rekos

Avielle Richman

Benjamin Wheeler

Allison Wyatt

And the educators:

Dawn Hochsprung

Mary Sherlach

Victoria Soto

Lauren Rousseau

Rachel D’Avino

Anne Marie Murphy

Six-year-olds.

I remember sitting on my couch watching the coverage and feeling physically ill.

My daughter was thirteen at the time.

Old enough to imagine it.

Old enough to ask questions.

President Obama cried on national television.

Congress debated expanded background checks.

The Manchin-Toomey amendment failed in 2013.

And parents like me added another layer of fear to our already overloaded nervous systems.

2016 — When It Wasn’t Just Schools

Pulse Nightclub. Orlando.

Forty-nine people killed in a place that was supposed to be joy.

A place of music, community, celebration.

Among them:

Edward Sotomayor Jr., 34

Stanley Almodovar III, 23

Luis Omar Ocasio-Capo, 20

Juan Ramon Guerrero, 22

Eric Ivan Ortiz-Rivera, 36

Peter O. Gonzalez-Cruz, 22

Darryl Roman Burt II, 29

Deonka Deidra Drayton, 32

Alejandro Barrios Martinez, 21

Kimberly Morris, 37

Akyra Monet Murray, 18

Luis S. Vielma, 22

Javier Jorge-Reyes, 40

Jason Benjamin Josaphat, 19

Cory James Connell, 21

Joel Rayon Paniagua, 32

Juan P. Rivera Velazquez, 37

Enrique L. Rios Jr., 25

Jean C. Nives Rodriguez, 27

Rodolfo Ayala-Ayala, 33

Frank Hernandez, 27

Miguel Angel Honorato, 30

Jerald Arthur Wright, 31

Leroy Valentin Fernandez, 25

Mercedez Marisol Flores, 26

Gilberto Ramon Silva Menendez, 25

Simon Adrian Carrillo Fernandez, 31

Tevin Eugene Crosby, 25

Jonathan Camuy Vega, 24

Christopher Andrew Leinonen, 32

Angel L. Candelario-Padro, 28

Jean Carlos Mendez Perez, 35

Yilmary Rodriguez Solivan, 24

Shane Evan Tomlinson, 33

Martin Benitez Torres, 33

Paul Terrell Henry, 41

Antonio Davon Brown, 29

Oscar A. Aracena-Montero, 26

Jonathan Antonio Rodriguez, 24

Brenda Lee Marquez McCool, 49

Amanda Alvear, 25

Franky Jimmy Dejesus Velazquez, 50

Christopher Joseph Sanfeliz, 24

Juan Chevez-Martinez, 25

Luis Daniel Wilson-Leon, 37

And more lives that continue to be remembered.

Public space itself felt unstable.

Schools. Nightclubs. Theaters. Concerts.

It wasn’t about one location anymore.

It was about unpredictability.

2018 — Parkland

Seventeen killed at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School:

Alyssa Alhadeff, 14

Scott Beigel, 35

Martin Duque Anguiano, 14

Nicholas Dworet, 17

Aaron Feis, 37

Jaime Guttenberg, 14

Chris Hixon, 49

Luke Hoyer, 15

Cara Loughran, 14

Gina Montalto, 14

Joaquin Oliver, 17

Alaina Petty, 14

Meadow Pollack, 18

Helena Ramsay, 17

Alex Schachter, 14

Carmen Schentrup, 16

Peter Wang, 15

By then, my son was in high school.

Every alert from the school district made my stomach drop.

Active shooter drills were normal.

Children practiced barricading doors the way we once practiced duck-and-cover for tornadoes.

And I carried anxiety like a permanent accessory.

My kids are grown now.

They are adults.

But my nervous system still flinches at “breaking news.”

I still sit facing exits in restaurants.

I still scan crowds.

Because motherhood for me did not begin with lullabies.

It began with Columbine.

April 19, 1999, I became a mother.

April 20, 1999, I became a vigilant one.

And for twenty-five years, I have lived in that space between love and fear — loving my children fiercely while quietly preparing for worst-case scenarios I pray never come.

That is what this country did to mothers like me.

Not overnight.

But slowly.

Layer by layer.

Year by year.

And now my children are grown.

And I am still unlearning what April 20 taught me.

What It Taught Me

April 20, 1999 taught me that safety in America is conditional.

It taught me that institutions are not guarantees. That brick buildings and locked doors do not equal protection. That metal detectors don’t measure grief in advance.

It taught me that motherhood is not just nurturing.

It is strategic planning.

It is contingency mapping.

It is rehearsing emergency scenarios in your head while packing lunchboxes.

It taught me that I would never again hear the words “It won’t happen here” and believe them.

Because it happened there. And then it happened somewhere else. And then it happened again.

It taught me how quickly the news cycle moves — how names scroll across a screen for a week, and then the country exhales and moves on.

But mothers don’t move on.

We absorb.

We catalog.

We internalize.

It taught me that trauma compounds.

Columbine was the introduction.

Sandy Hook was the fracture.

Parkland was confirmation.

Uvalde was the reopening of wounds that never fully closed.

Each event didn’t just exist as a headline — it layered itself into my nervous system.

Psychologists call it cumulative stress exposure.

When trauma isn’t singular, but repetitive.

When your body never returns to baseline.

I didn’t know that’s what was happening to me.

I just knew that my heart rate would spike at school pickup lines.

That loud noises in public made me tense.

That I memorized exit routes without consciously deciding to.

It taught me that fear and love can live in the same breath.

I loved my children fiercely.

And because I loved them fiercely, I feared fiercely.

It taught me that policy debates feel abstract until you’re holding a newborn and imagining a hallway twenty years in the future.

It taught me that grief doesn’t belong only to families directly affected.

There is communal grief.

National grief.

A generation of parents who silently recalibrated their expectations of safety.

It taught me that children now grow up with vocabulary I didn’t learn until adulthood:

Lockdown. Active shooter. Shelter in place. Barricade.

My children practiced survival drills in elementary school.

We practiced fire drills.

That difference matters.

It taught me that resilience is not the absence of fear.

It is functioning despite it.

I still showed up to PTA meetings.

Still went to football games.

Still allowed sleepovers.

Still let them become independent.

But there was always a quiet calculation running in the background.

And now?

Now they are adults.

They move through the world without asking permission.

And I am proud of them.

But my body still reacts to breaking news alerts.

Still pauses when I see police lights clustered in unusual numbers.

Still exhales slowly when I hear their voices on the phone.

April 20, 1999 taught me that motherhood in America requires an extra layer of vigilance that no one warns you about in childbirth classes.

No one tells you that alongside feeding schedules and first steps, you may also inherit a permanent relationship with anxiety.

But here is what else it taught me:

It taught me that I am stronger than the fear.

Because despite it, I raised two children who are compassionate.

Who are aware.

Who understand the world’s fractures but are not defined by them.

It taught me that love is not fragile.

It is ferocious.

And even in a country where safety sometimes feels negotiable, love is not.

April 19, 1999 made me a mother.

April 20, 1999 made me vigilant.

The years after made me informed.

And now — decades later — I am learning how to soften again.

Not because the world is suddenly safe.

But because my children survived it.

And so did I.

But survival is not the same as peace.

There is a difference between living through something and being untouched by it.

For twenty-five years, I lived in a low hum of alertness that I didn’t even recognize as abnormal anymore.

It was just… motherhood.

If the school number popped up on my phone, my heart dropped before I answered.

If my kids were late coming home, I didn’t assume traffic — I assumed worst-case scenario and then forced myself to breathe through it.

When they were teenagers and wanted to go to the movies, to the mall, to concerts, I said yes.

But my yes always came with mental math.

Where is it? How many exits? How fast could I get there? Do they know to run? Do they know to hide? Do they know to call me?

Other parents worried about grades and curfews.

I worried about floor plans.

And that does something to a person.

When fear becomes habitual, it rewires you.

Neuroscience tells us that repeated exposure to threat — even indirect threat through media — strengthens neural pathways associated with danger detection. The amygdala becomes reactive. The body prepares for impact even when there is none.

That was me.

My children grew up during a time when lockdown drills were normalized. They learned to sit quietly in dark classrooms, to stack desks against doors, to silence their phones.

That wasn’t hypothetical.

That was curriculum.

And I learned something else in those years:

Children adapt faster than adults.

They would come home and casually mention, “We had a lockdown drill today.”

Casually.

Like it was a spelling test.

Meanwhile, I would excuse myself to the bathroom and let my hands stop shaking.

Because to them, it was routine.

To me, it was Columbine replaying in slow motion.

It was Sandy Hook’s tiny faces.

It was Parkland’s hallway footage.

It was every mother who had once buckled a seatbelt and said, “Have a good day at school.”

There is a particular kind of grief that lives in parents who have not lost a child but have watched other parents lose theirs.

It is anticipatory.

It is protective.

It is relentless.

I did not lose my children to violence.

But I carried the possibility like a shadow.

And here’s the part people don’t talk about:

Anxiety doesn’t evaporate when your kids turn eighteen.

It doesn’t clock out at graduation.

It evolves.

Now I worry about grocery stores.

Movie theaters.

Nightclubs.

Churches.

Parades.

College campuses.

Public space itself feels conditional.

I still sit facing exits.

I still note security presence.

I still check my phone too quickly when there’s a national alert.

Because April 20, 1999 did not just teach me fear.

It taught me awareness.

And awareness is hard to put back down.

But here’s the truth that took me years to accept:

Constant vigilance is not the same thing as protection.

At some point, I had to ask myself:

Is my anxiety keeping them safe? Or is it keeping me trapped?

Because love should not feel like a permanent state of alarm.

And that’s where the unlearning began.

I began therapy.

I began researching trauma responses.

I began recognizing that hypervigilance had become my default setting.

Not because I was weak.

But because I was conditioned.

When a society experiences repeated public trauma, individuals internalize it.

It becomes cultural muscle memory.

I am part of the Columbine generation of mothers.

We became parents at the beginning of modern mass-casualty awareness.

We raised children in the era of “active shooter.”

We learned to love loudly and worry quietly.

And now, decades later, I am learning something new:

Resilience does not mean pretending it didn’t affect me.

Resilience means acknowledging that it did.

It shaped me.

It made me protective.

It made me strategic.

It made me sometimes overbearing.

It made me sometimes afraid.

But it also made me intentional.

It made me present.

It made me cherish ordinary days in a way I might not have otherwise.

When my son graduated in 2020, in the middle of a pandemic, I cried.

Not just because he finished school.

But because he finished school.

Because from April 20, 1999 forward, that milestone was never guaranteed in my mind.

When my daughter built her own life, independent and strong, I felt something unclench inside me.

They made it.

And so did I.

Motherhood did not break me.

But it reshaped me.

And if I am honest, I am still reshaping.

Still learning how to sit in a restaurant without scanning.

Still teaching my body that not every loud noise is a warning.

Still reminding myself that vigilance and peace do not have to be enemies.

April 19, 1999 gave me my daughter.

April 20, 1999 gave me a new lens on the world.

The years after gave me anxiety.

But they also gave me clarity.

Because what those tragedies ultimately taught me is this:

Life is fragile.

Time is not promised.

And love — loud, consistent, stubborn love — is the only thing that outlasts fear.

My children grew up in an America that made them practice survival.

I grew up as a mother learning to balance fear and freedom.

And today, as they move through the world on their own, I am finally learning to exhale.

Not because nothing will ever happen again.

But because I cannot live inside the possibility forever.

I became a mother in one America.

I raised children in another.

And somewhere between those two versions of this country, I became stronger than the fear that tried to define me.

About the Creator

Dakota Denise

Every story I publish is real lived, witnessed, survived, by myself or from others who trusted me to tell the story. Enjoy 😊

Comments (1)

The line “my nervous system now lived outside my own body” hasn’t left me. You didn’t just describe motherhood you described what happens when love becomes permanently tied to uncertainty. The way you carried both fierce love and quiet fear at the same time felt incredibly real and deeply human.