Too Many Satellites? Earth’s Orbit Is Racing Toward a Catastrophe — But We Can Still Stop It

As mega-constellations multiply and space debris grows, humanity faces a silent crisis above our heads. The good news? Smart policy, better technology, and global cooperation can prevent disaster.

The night sky once belonged to stars. Today, it increasingly belongs to satellites.

In just the past decade, Earth’s orbit has transformed from a relatively quiet domain into a crowded highway of metal, electronics, and ambition. Thousands of satellites now circle our planet, delivering internet services, tracking weather patterns, enabling GPS navigation, and supporting military communications. But as space becomes more commercialized and competitive, a dangerous question looms: Are we putting Earth’s orbit at risk of collapse?

This is not science fiction. Scientists have long warned about a scenario known as the Kessler Syndrome, where cascading satellite collisions create so much debris that parts of orbit become unusable for generations. With mega-constellations rapidly expanding, that risk is no longer theoretical.

Yet catastrophe is not inevitable. With decisive global action, we can protect orbit before it becomes a junkyard.

The Rise of Mega-Constellations

The biggest driver of orbital crowding is the rise of private satellite networks. Companies such as SpaceX have launched thousands of satellites under the Starlink program to deliver global broadband internet. Other corporations and nations are racing to deploy similar systems.

This rapid expansion has changed the scale of activity in low Earth orbit (LEO). Historically, a few thousand satellites were launched over decades. Now, that many can be deployed in just a few years.

The benefits are undeniable:

Rural communities gain internet access.

Disaster zones maintain communication.

Global navigation systems improve.

Scientific monitoring becomes more precise.

But every satellite adds congestion — and every object in orbit travels at speeds exceeding 17,000 miles per hour. At that velocity, even a small fragment of debris can destroy a spacecraft.

The Growing Cloud of Space Debris

Orbit is already littered with remnants of past missions: defunct satellites, rocket bodies, paint flecks, and fragments from collisions.

One major warning sign came in 2009 when an active U.S. communications satellite collided with a defunct Russian satellite. The crash created thousands of debris pieces, many of which remain in orbit today.

NASA estimates that millions of debris fragments — from tiny shards to large objects — now circle Earth. While larger pieces are trackable, smaller fragments are nearly impossible to monitor but still powerful enough to cause catastrophic damage.

The danger lies in chain reactions. If one collision triggers others, the resulting cascade could create a debris field dense enough to make certain orbital regions unusable. That’s the heart of the Kessler Syndrome theory proposed in 1978.

If that happened, satellites essential for:

GPS navigation

Weather forecasting

Climate monitoring

Banking transactions

Global communications

could be severely disrupted.

Imagine losing real-time weather tracking during hurricane season. Or global navigation systems failing during emergency response. The consequences would ripple across economies and security systems worldwide.

Why Regulation Hasn’t Kept Up

Space law was designed in an era when only governments operated in orbit. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty established that space belongs to all humanity and should be used peacefully. But it did not anticipate thousands of private satellites launched annually.

Today, national regulators approve launches, but global enforcement mechanisms remain weak. There is no single authority managing orbital traffic like air traffic control on Earth.

Companies are encouraged — but not always required — to remove satellites from orbit after their missions end. While many operators promise responsible deorbiting plans, compliance varies, and enforcement remains inconsistent.

In a competitive industry, speed often wins over caution.

Climate and Astronomical Impacts

Orbital congestion is not only a technological concern — it also affects science and the environment.

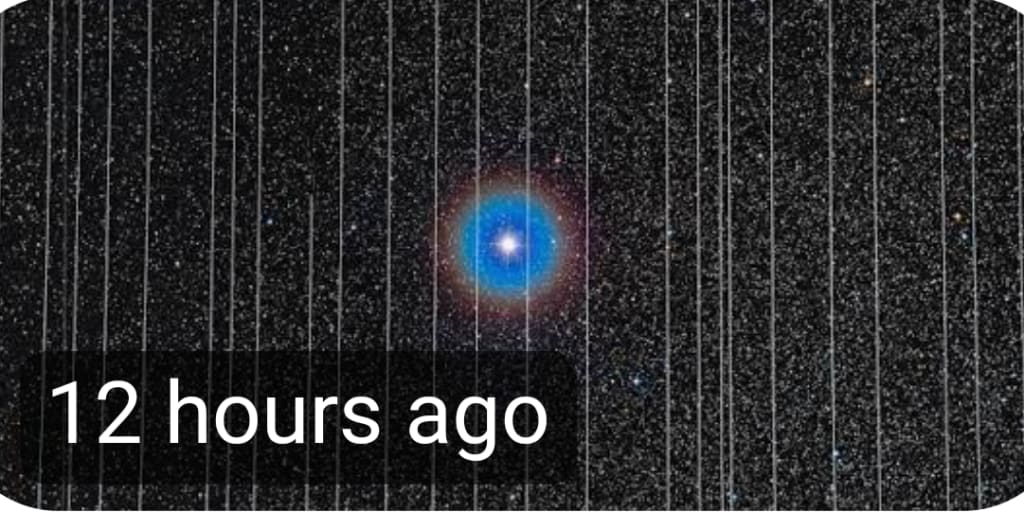

Astronomers have reported increased interference from satellite streaks crossing telescope images. Ground-based observatories, critical for studying distant galaxies and detecting potentially hazardous asteroids, now face growing visual pollution.

There are also concerns about atmospheric effects. When satellites burn up during reentry, they release particles into the upper atmosphere. Scientists are still studying the long-term environmental impacts of these materials.

What began as a communications revolution may be creating new, poorly understood environmental risks.

How We Can Prevent Disaster

The situation is serious — but solvable.

1. Stronger International Rules

Governments must update space treaties to address commercial mega-constellations. Binding international standards for debris mitigation, satellite lifespan, and end-of-life disposal are essential.

2. Mandatory Deorbiting Requirements

Satellites should be required to deorbit within a strict timeframe after their missions end. Automated systems can ensure failed satellites safely reenter Earth’s atmosphere.

3. Active Debris Removal

Emerging technologies aim to capture and remove large debris objects. Robotic arms, nets, and harpoon-style systems are being tested. Investing in these solutions now could prevent future cascade events.

4. Orbital Traffic Management

A global space traffic coordination system would help track satellites and avoid collisions. Improved data sharing between governments and private companies is crucial.

5. Smarter Satellite Design

Future satellites can be designed to burn up completely on reentry, leaving no residual fragments. Modular designs may also extend lifespans and reduce replacement frequency.

The Stakes Are Higher Than We Think

Orbit is not infinite. Certain altitudes are uniquely valuable for communications and Earth observation. Once contaminated by debris, they may be unusable for decades — or longer.

We depend on satellites more than most people realize. From ATM withdrawals to airline navigation and climate monitoring, orbital infrastructure underpins modern civilization.

Losing access would not just be an inconvenience. It would be a systemic shock to global stability.

A Narrow Window of Opportunity

Humanity stands at a crossroads. We are in the early stages of a space economy projected to be worth trillions of dollars. But without guardrails, growth could undermine itself.

The story of Earth’s orbit does not have to end in catastrophe. History shows that international cooperation can address shared risks — from nuclear arms control to ozone depletion.

Space is humanity’s shared frontier. If we treat it as a dumping ground, we risk losing one of our greatest technological achievements. If we treat it responsibly, it can remain a resource for generations.

The sky above us is growing busier every day. Whether it becomes a graveyard of debris or a sustainable engine of innovation depends on decisions being made right now.

The catastrophe is on track — but it is still within our power to stop it.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.