The Cemetery of Curiosity: How School Became the Place Where Questions Go to Die

We Built a System That Rewards Right Answers and Punishes the Wrong Ones, Forgetting That Discovery Lives in the Space Between

There is a moment that happens somewhere between kindergarten and fourth grade, and it breaks my heart every time. It is the moment when the hand stops going up. The moment when the question dies on the lips. The moment when the child who once asked "why" about everything—why is the sky blue, why do leaves fall, why do people die, why why why—learns that asking questions is risky. That the wrong question makes you look stupid. That the right answer matters more than the curious mind. That school is not a place of discovery but a place of performance.

This moment is not accidental. It is not an unfortunate side effect. It is the logical outcome of a system designed for something other than nurturing curiosity. We have built an education machine that treats children as empty vessels to be filled rather than fires to be lit, that measures success by correct answers rather than powerful questions, that standardizes minds in the name of efficiency and calls it excellence. The result is not educated children but trained ones—children who have learned to suppress their natural wonder in exchange for approval, compliance, and the fragile safety of being right.

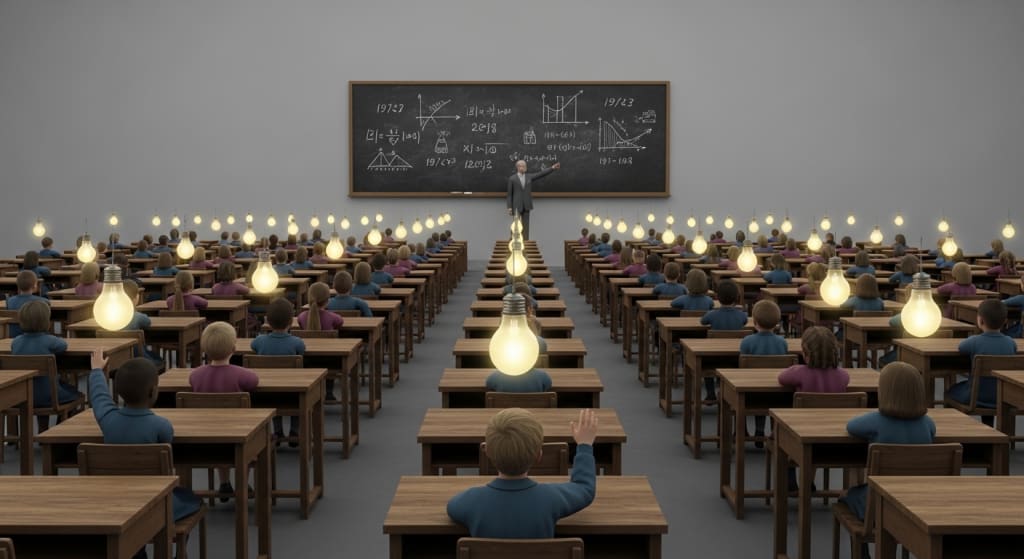

Watch a classroom in action and you will see the mechanism at work. The teacher asks a question. A dozen hands shoot up. One child is called upon and gives the answer the teacher expects. The class moves on. The children who were not called upon lower their hands, some disappointed, some relieved. The child who was considering a different answer, a more interesting answer, an answer that might have led somewhere unexpected, keeps silent because they have learned that divergence is not rewarded. The question that could have opened a door closes instead, and another small death of curiosity occurs.

This happens thousands of times, across millions of classrooms, every single day. By the time children reach middle school, most have internalized the lesson completely: school is about getting it right, not about wondering what might be. The questions they ask now are strategic—will this be on the test, how many pages does it have to be, what do you want me to say. The wonder that once blazed has been banked, smothered by rubrics and grades and the constant implicit message that what matters is not the journey but the destination, not the asking but the knowing.

The tragedy is compounded by what we have forgotten: that the ability to ask good questions is more valuable than the ability to recite correct answers. In a world where information is instantly accessible, memorization has become nearly obsolete. Any fact you need is in your pocket, available in seconds. But the questions that lead to discovery, innovation, and wisdom—those cannot be Googled. Those require a mind trained not in recall but in wonder. Those require the very curiosity our schools systematically extinguish.

Consider the greatest minds in human history. They were not distinguished by their ability to answer existing questions but by their courage in asking new ones. Einstein asked what the world would look like if you could ride a beam of light. Newton asked why an apple falls straight down. Curie asked what was causing those mysterious rays. Darwin asked why finches on different islands had different beaks. These questions were not in any textbook. They emerged from minds that had never learned to stop wondering. They emerged from the very curiosity our schools have been quietly killing for generations.

I think about a boy I met in a third-grade classroom, years ago, when I was visiting as a guest. The class was studying plants, and the teacher had just explained that plants need sunlight to grow. The boy raised his hand and asked, "But what about the plants in the cave? The ones that grow in total darkness? How do they live?" The teacher paused, visibly annoyed at the interruption to her lesson plan. "That's not what we're talking about right now," she said. "We're talking about normal plants." The boy's face fell. His hand did not go up again for the rest of the hour. I have never forgotten that moment. I have never forgiven it.

That boy was asking a real question. He was thinking beyond the script, connecting what he was learning to something he had heard or read elsewhere. He was doing exactly what an educated mind should do. And he was shut down for it. Not cruelly, not maliciously—just efficiently, in the interest of covering the material, staying on schedule, maintaining order. The message was clear: your curiosity is inconvenient. Your question is a distraction. Your mind is supposed to stay in the lane we have built for it.

The cumulative effect of a million such moments is a population of adults who have forgotten how to wonder. Adults who accept what they are told without examination. Adults who feel uncomfortable with uncertainty, who need answers even when none exist, who have lost the capacity to sit with a question and let it work on them. Adults who are easily manipulated because they never learned to ask who benefits from this information, what is being left out, why this framing and not another. The cemetery of curiosity is vast, and we are all buried there to some degree.

There are teachers who resist this. They are heroes, though they would never call themselves that. They are the ones who welcome the unexpected question, who follow the digression, who let the lesson plan bend to accommodate wonder. They are the ones who say "I don't know, let's find out together" instead of "that's not what we're talking about." They are the ones who understand that their real job is not to transmit information but to cultivate minds, to protect the flame of curiosity from the winds of standardization. They do this work quietly, often without support, sometimes at risk to their own evaluations. They are the reason any of us retained any wonder at all.

But individual teachers cannot overcome a system. The system must change. It must be rebuilt around different assumptions—not that children need to be filled with knowledge, but that they need to be equipped to pursue it. Not that learning is a product to be measured, but that it is a process to be lived. Not that questions are obstacles to coverage, but that they are the very point of education itself.

What would this look like? It would look like classrooms where the most common question from teachers is not "what is the answer" but "what are you wondering about." It would look like assessments that value the quality of questions asked as much as the accuracy of answers given. It would look like curricula built not around predetermined content but around authentic problems that require genuine inquiry. It would look like grades that measure growth in wonder rather than proficiency in recall. It would look like schools that see their mission not as preparing workers but as nurturing whole human beings.

There are places where this is already happening. Schools that have abandoned traditional grading in favor of narrative feedback. Schools that devote significant time to student-driven projects. Schools that treat failure not as a final judgment but as essential data in the learning process. Schools that understand that the goal is not to produce students who all know the same things but to produce graduates who all know how to learn. These schools are not utopian fantasies; they exist, they work, and their students emerge with their curiosity intact.

The rest of us, the products of the old system, have work to do. We must recover the wonder that was schooled out of us. We must relearn the art of asking good questions—questions that cannot be answered by a quick search, questions that open rather than close, questions that keep us humble in the face of complexity. We must create environments, in our homes and workplaces and communities, where curiosity is welcomed rather than punished. We must become, ourselves, the learners we wish we had been allowed to be.

And we must insist that the children coming after us are given something better. We must demand schools that see them as whole beings, not test scores. We must support teachers who prioritize wonder over coverage. We must question the assumptions that have shaped education for a century and ask whether they serve the world our children will inherit. We must, in short, become the advocates for curiosity that we needed when we were young.

The cemetery of curiosity is full, but it does not have to keep growing. Every question asked and welcomed is a resurrection. Every wonder honored is a rebellion. Every child who leaves school still asking why is proof that the system can be resisted. The goal is not to fill minds but to ignite them. The goal is not to produce right answers but to cultivate powerful questions. The goal is not to train workers but to nurture humans who will never stop wondering.

The hand is still raised. The question is still waiting. The light bulb still flickers, even in the dark. Let us finally, after all these years, call on the child in the back with the strange question and the curious eyes. Let us listen to what they have to ask. Let us follow where the question leads. Let us remember that education, at its best, is not the transmission of answers but the cultivation of wonder. And let us begin again, together, in the only place learning has ever happened: in the fertile space between a good question and a mind brave enough to ask it.

About the Creator

HAADI

Dark Side Of Our Society

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.