Pluto the Unknown Hero of World War II

How engineering helped Britain win World War II

Twenty minutes from where I live is a haunted landscape known as Dungeness. You can get to Dungeness three ways.

Driving would take you past some of the most desolate landscapes. You could choose to go by sea or on the miniature railway. This railway brought the equipment to Dungeness to build the PLUTO pipeline in World War II.

The project was ambitious if the titles weren't. PLUTO stood for Pipeline Under the Ocean.

How Pluto came into orbit

Motor fuel was recognised as the difference between the success or failure of any battle. Leaders knew that guaranteeing fuel supply was imperative to win World War II.

The standard process was for the fuel to be transported by tankers into the war zone. Here, they were in danger of enemy attack from the air and sea. The delivery was also at the mercy of the weather.

What was needed was a pipeline that would pump the fuel under the sea, so that is what was designed.

Designing the Impossible

Arthur Hartley, chief engineer with the Anglo-Iranian Oil company and Admiral Louis Mountbatten (Prince Phillip's Uncle) were the first to discuss the problem weeks after D-Day.

They planned to supply the petrol from storage tanks that they would situate in the South of England. This petrol would supply the Allied armies in France.

Eisenhower acknowledged the significance of what they were planning. It was an operation as significant as the Mulberry Harbours, another operation routed along the same coastline.

Mulberry harbours were ingenious temporary ports used during World War II, particularly during the D-Day landings in 1944.

Designed to address the logistical challenge of rapidly supplying Allied forces with equipment and troops on the shores of Normandy, these artificial harbours consisted of massive prefabricated components that could be towed across the English Channel and assembled on the beach.

They played a pivotal role in the success of the Normandy invasion, facilitating the offloading of troops, vehicles, and supplies, and enabling the rapid buildup of Allied forces on the continent.

Implementation

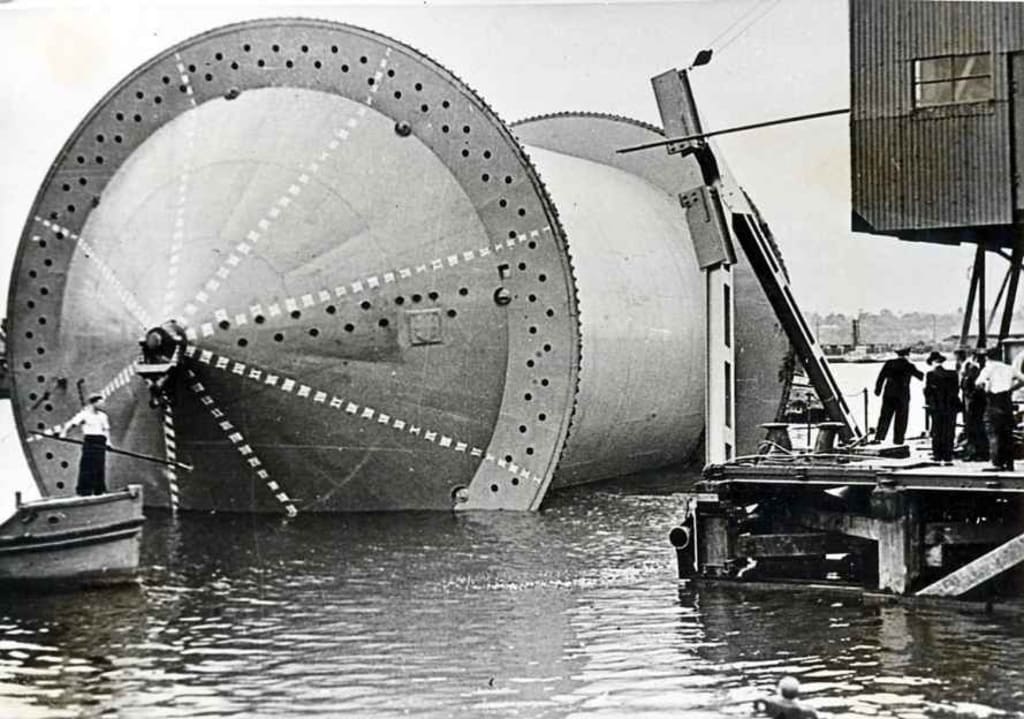

Work on developing the PLUTO began in 1942. The plan was to construct a flexible yet pressure-resistant pipe.

The construction was a slow process. The fuel stored along the south coast was also an obvious target for the Luftwaffe.

To avoid these attacks, it was decided to construct a network of pipelines from oil terminals throughout the United Kingdom. Liverpool and Bristol were two of the biggest providers pumping the fuel down to Dungeness and the Isle of Wight.

From either of these locations, the distance to France was at its shortest—Dungeness to Calais, the Isle of Wight to Cherbourg.

The pipeline ran under the Mersey River, down the length of England to the South.

Many of the pumping stations along the route were disguised as bungalows, barns, gravel pits, and, in one case, an ice cream shop to further minimise the risk of attack from the air.

Completion

There were many delays in completing the pipeline, but it was fully operational on 12 August 1944, only two years after its conception.

During this stage of the war, the Allied troops had made significant progress; fuel had become a priority. The pipeline provided this.

It is estimated that for the eight months it was operational, it delivered 172 gallons of fuel to France. As the troops advanced, the pipeline was transferred from the Isle of Wight to Dungeness, a shorter route.

PLUTO was the first undersea oil pipeline and significantly contributed to the war effort. It also advanced pipeline development for years to come.

After the war, the lines were decommissioned, and the lead they contained was salvaged. Rumour has it that the lead used in the pipes came from the bombs Hitler dropped on England.

About the Creator

Sam H Arnold

Fiction and parenting writer exploring the dynamics of family life, supporting children with additional needs. I also delve into the darker narratives that shape our world, specialising in history and crime.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.