The Annotated Elephant Man

Commentary on the Famous Essay by Sir. Frederick Treves (Excerpt)

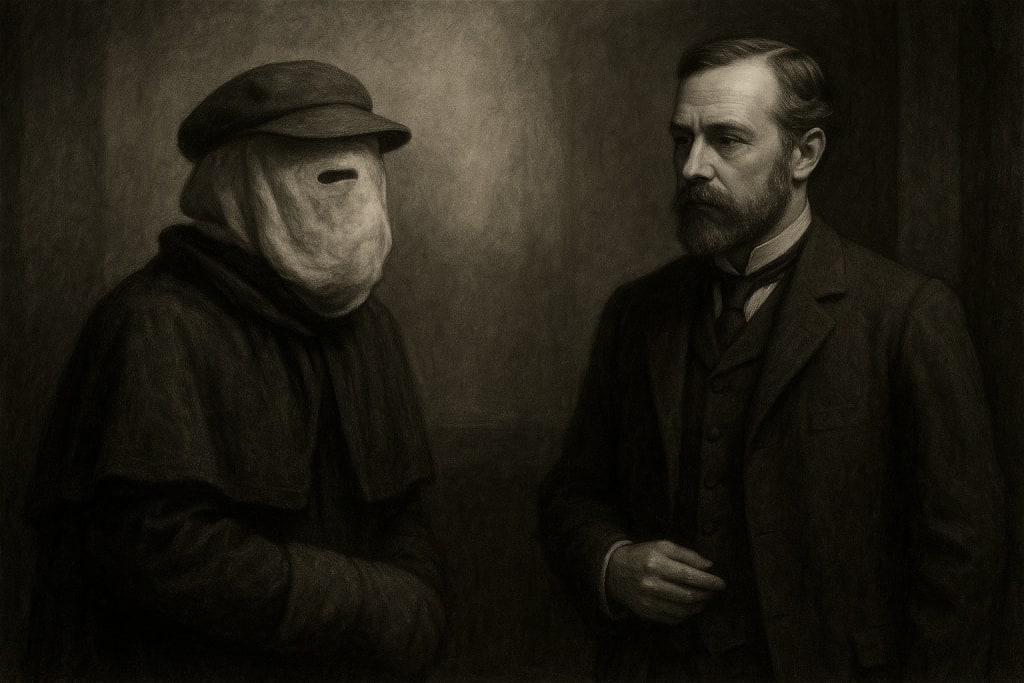

The discovery as a child of the haunting, tragic life story of Jospeh Carey "John" Merrick was one of the most defining creative and spiritual apsects of my personal development. Throwing a tantrum as a child, not wanting my parents to watch the stage play starring Philip Anglim as "John Merrick, " and Kevin Conway, and later seeing that same play rebroadcast in images that haunt me, dream-like, to this day; images that seemed to have welled up from some past existence. Images of an eerie, quiet, void-like place wherein a Victorian presumed "Doctor" is unaccountably taken by the prone figure of someone we never see. Someone that a mob or crowd has captured, lifting them above their shoulders, holding them up to the light of God, outside a growing circle of musty darkened despair.

The dreamlike memories, the vast silence of internal states, the dredging up of something quite beyond a normal, linear memory in a logical timeframe, all defined who I was and am. "There was a world beyond, that none of them could see. But he had been there. He knew." Lines from a novel I wrote, many decades later, based on the life of Joseph Carey Merrick, the horribly distorted and misshapen creature whose gentle, long-suffering soul goes with me. Always. Even in the depths of the most foul places wherein I sometimes sojourn.

Because his face is My face. It is the face of modern ugliness. David Lynch, in his film of The Elephant Man, juxtaposed the stark Victorian environment with an even more stark, brutal and dehumanizing background of industrialization in the late Nineteenth century--men become slaves, as Thea von Harbou demonstrated also in her novel of Metropolis (the basis for Fritz Lang's film), to the unforgiving, unreasoning machines ("Terrible things these machines," comments Treves (Anthony Hopkins) in the film, "you can't reason with them, you know."), the endless grinding of which, the pulsing and pumping enginery of energy and time, making manifest an often grueling machinery of fate. We might call this God, and the Will of God is played out, inexorably, in the life of Merrick, who is tormented, and alternately, blessed by a strange, and inscrutable destiny.

Joseph Merrick, erroneously referred to as "John Merrick," for reasons that remain unclear (a mistake endlessly repeated in fictional representations of his life), lived to the age of twenty-eight at Bedstead Square, in London, at the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel, a place where Jack the Ripper contemporaneously roamed, searching for victims. He found them. His ugliness lurked within; his facade was undoubtedly one of banal normality; His chameleon cloak.

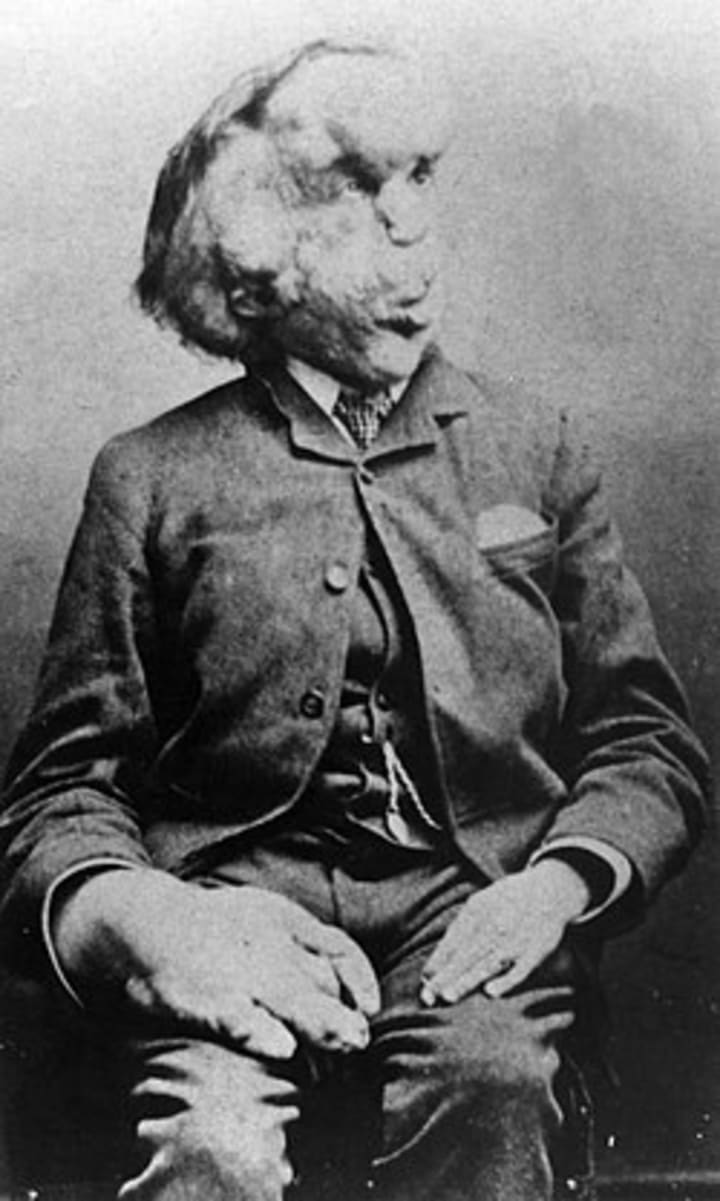

Merrick's hideous ugliness, a misshapen and humongous head requiring a hood and cloak, the image of which has become iconic and is still unnerving, was displayed on his exterior surface--the surface that men and women value, and by which they judge all souls embodied.

But Merrick's soul did not reflect the facial repulsion that he wore like a grim mask, as isolated, as the actual Treves observed, as "The Man in the Iron Mask." His soul, gentle, determined, a survivor of a trauma few of us can ever know, returned to the Infinte. To be with Bernard Pomerance, and David Lynch, David Bowie, and John Hurt; his interpreters and those artists and creative souls that loved and nurtured his mythology. And, of course, with Sir. Frederick Treves.

And with his Mary Jane Merrick. And so, as I once wrote of him, "He lay down and slept in the bosom of God."

And I also wrote that, "Wherever it was in the mind of God he now rested, Joseph Merrick was dreaming."

And all of us dream

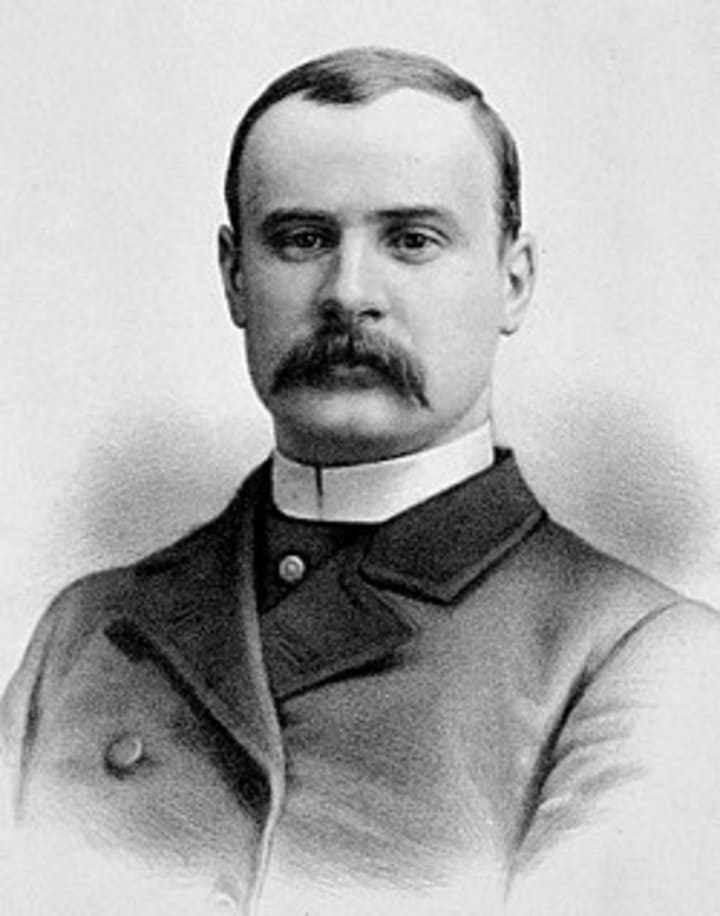

Note. What follows is a reprint of the classic essay "The Elephant Man" by Sir. Frederick Treves, his rescuer and protector. Treves is a morally ambiguous character in some ways, but he seems well-intentioned. This is an excerpt of the entire essay with commentary, as to repost the whole thing here would be rather cumbersome. The small book will soon follow for those interested in reading it all.

'Tis true my form is something odd, but blaming me is blaming God. If I could make myself a new, I would not fail in pleasing you.

If I could stretch from pole to pole, or grasp the ocean with a span, I would be measured by the soul, the mind's the standard of the man."

Isaac Watts, "False Greatness"

“IN the Mile End Road, opposite to the London Hospital, there was (and possibly still is) a line of small shops. Among them was a vacant greengrocer’s which was to let. The whole of the front of the shop, with the exception of the door, was hidden by a hanging sheet of canvas on which was the announcement that the Elephant Man was to be seen within and that the price of admission was twopence. Painted on the canvas in primitive colours was a life-size portrait of the Elephant Man. This very crude production depicted a frightful creature that could only have been possible in a nightmare.”

The beginning of this essay brings us to the gate by which, once passed, we will proceed to the inner chamber where the fairy tale prince, turned by cruel fate into an ogre, waits, hunched over a burning brick. The opening lines are classic, and they place the reality of the situation in an historical timeframe, a context that assures us that what follows is a true experience of a man, a doctor, whose journey into the bowels of the surrounding neighborhood are motivated by professional and personal curiousity.

It was the figure of a man with the characteristics of an elephant. The transfiguration was not far advanced. There was still more of the man than of the beast. This fact—that it was still human—was the most 2repellent attribute of the creature. There was nothing about it of the pitiableness of the misshapened or the deformed, nothing of the grotesqueness of the freak, but merely the loathsome insinuation of a man being changed into an animal. Some palm trees in the background of the picture suggested a jungle and might have led the imaginative to assume that it was in this wild that the perverted object had roamed. ”

Appealing to the fascination with foreign lands, Treves sets up the contrast that he will exploit later—the contrast of Merrick being portrayed as a monstrous, even powerful character. The truth, reality, was exactly the opposite of course—Merrick was a weak, pathetic, very ill or even dying man, one hideously afflicted by a terrible, unknown, grossly disfiguring disease. The sideshow canvas was appealing to the morbid curiosity of those seeking sensational entertainment as a diversion of the drab, tedious monotony of their impoverished existences.

When I first became aware of this phenomenon the exhibition was closed, but a well-informed boy sought the proprietor in a public house and I was granted a private view on payment of a shilling. The shop was empty and grey with dust. Some old tins and a few shrivelled potatoes occupied a shelf and some vague vegetable refuse the window. The light in the place was dim, being obscured by the painted placard outside. The far end of the shop—where I expect the late proprietor sat at a desk—was cut off by a curtain or rather by a red tablecloth suspended from a cord by a few rings. The room was cold and dank, for it was the month of November. The year, I might say, was 1884.

There is a feeling of the deep poverty, the drab, mundane aspects of Victorian life in a slum—the rotting vegetable matter of the shelves. Why was it abandoned? A few stinking potatoes perhaps, but hungry bellies would savor them. Instead, the space that formerly nourished a body has become a place wherein a disfigured, wildly distorted body will be put on display. The mundane, musty filth of the disused store now sells a commodity just as valuable to the eager, the curious; those poor, huddled Victorians who come seeking a forbidding thrill.

The showman pulled back the curtain and revealed a bent figure crouching on a stool and covered by a brown blanket. In front of it, on3 a tripod, was a large brick heated by a Bunsen burner. Over this the creature was huddled to warm itself. It never moved when the curtain was drawn back. Locked up in an empty shop and lit by the faint blue light of the gas jet, this hunched-up figure was the embodiment of loneliness. It might have been a captive in a cavern or a wizard watching for unholy manifestations in the ghostly flame. Outside the sun was shining and one could hear the footsteps of the passers-by, a tune whistled by a boy and the companionable hum of traffic in the road.

Here we are introduced to Joseph “John” Merrick—an erroneous name given him, in this essay, by Treves. This has puzzled commentators, but can perhaps be explained best as Treves simply affording Merrick a degree of anonymity—making him an “everyman.” An original manuscript of The Elephant Man includes the name Joseph, which is drawn out by Treves and has the substitute name “John” written above. Treves motivations for doing so are simply a matter of conjecture.

Merrick, described as a “picture of loneliness,” is accorded the mien of a fantastical character. Outside, Treves informs us he can hear the “companionable hum” in the street—the comings and goings of men and women that operate inside the world of workaday, chronologically logical life. Merrick, by contrast, seems outside the stream, the disused greengroers might as well be the gateway to a dark, and troubled land—a place where Merrick has emerged, as if from the dregs of an unquiet dream.

The showman—speaking as if to a dog—called out harshly: “Stand up!” The thing arose slowly and let the blanket that covered its head and back fall to the ground. There stood revealed the most disgusting specimen of humanity that I have ever seen. In the course of my profession I had come upon lamentable deformities of the face due to injury or disease, as well as mutilations and contortions of the body depending upon like causes; but at no time had I met with such a degraded or perverted version of a human being as this lone figure displayed. He was naked to the waist, his feet were bare, he wore a pair of threadbare trousers that had4 once belonged to some fat gentleman’s dress suit.

Treves refers to the “Thing” standing, the blanket sliding away to reveal, “the most disgusting specimen of humanity that I have ever seen.” This is the detached, even degrading language of a medically curious expert on diseases and deformities. “In the course of my profession I had come upon lamentable deformities of the face due to injury or disease, as well as mutilations and contortions of the body depending upon like causes; but at no time had I met with such a degraded or perverted version of a human being as this lone figure displayed.”

Treves is here trying to find an approximate to the image of Merrick. He wants to try and reconcile himself to the sheer magnitude of his affliction. He notes the showman (presumably Tom Norman) spoke, “as if speaking to a dog.” The inference that Merrick is cruelly misued, as if Norman treated him “like an animal,” is not borne out even by Merrick's own testimony. Norman was actually, in Merrick's view, much more of a business partner. Merrick had, for the most part, a greater degree of autonomy than what later fictional depictions would suggest. Treves himself must have been trying to exculpate his own perhaps often questionable motives. His moral ambiguity, which is depicted in stage and film adaptations of ever troubling him, does not seem so apparent here, but perhaps can be read as a vague subtext.

From the intensified painting in the street I had imagined the Elephant Man to be of gigantic size. This, however, was a little man below the average height and made to look shorter by the bowing of his back. The most striking feature about him was his enormous and misshapened head. From the brow there projected a huge bony mass like a loaf, while from the back of the head hung a bag of spongy, fungous-looking skin, the surface of which was comparable to brown cauliflower. On the top of the skull were a few long lank hairs. The osseous growth on the forehead almost occluded one eye. The circumference of the head was no less than that of the man’s waist. From the upper jaw there projected another mass of bone. It protruded from the mouth like a pink stump, turning the upper lip inside out and making of the mouth a mere slobbering aperture. This growth from the jaw had been so exaggerated in the painting as to appear to be a rudimentary trunk or tusk. The nose was merely a lump of flesh, only recognizable as a nose from its position. The face was no more capable of expression than a block of gnarled wood. The back was horrible, because5 from it hung, as far down as the middle of the thigh, huge, sack-like masses of flesh covered by the same loathsome cauliflower skin.

Treves graphically displays the disgust of Merrick's body—a mutated landscape wherein conventional explanation is rendered meaningless by the sheer enormity of the distortions. A “bony mass like a loaf,” shares a space with “cauliflower-like skin,” and a face with a trunk-like growth and a lip upturned, making of the mouth “a mere slobbering aperture.” Treves notes that Merrick is not capable of any expression, his face being inert as “A block of wood.”

Treves later notes that, “Merrick could weep, but he could not smile.”

The right arm was of enormous size and shapeless. It suggested the limb of the subject of elephantiasis. It was overgrown also with pendent masses of the same cauliflower-like skin. The hand was large and clumsy—a fin or paddle rather than a hand. There was no distinction between the palm and the back. The thumb had the appearance of a radish, while the fingers might have been thick, tuberous roots. As a limb it was almost useless. The other arm was renmarkable by contrast. It was not only normal but was, moreover, a delicately shaped limb covered with fine skin and provided with a beautiful hand which any woman might have envied. From the chest hung a bag of the same repulsive flesh. It was like a dewlap suspended from the neck of a lizard. The lower limbs had the characters of the deformed arm. They were unwieldy, dropsical looking and grossly misshapened.

Treves tears down the boundaries between human, animal, and even vegetable in attempting to describe a unique prodigy of nature—Merrick is atomized, divided and inspected, and approximated to whatever Treves can grasp mentally to use as a descriptor.

To add a further burden to his trouble the wretched man, when a boy, developed hip disease, which had left him permanently lame, so that he could only walk with a stick. He was thus denied all means of escape from his tormentors.6 As he told me later, he could never run away. One other feature must be mentioned to emphasize his isolation from his kind. Although he was already repellent enough, there arose from the fungous skin-growth with which he was almost covered a very sickening stench which was hard to tolerate. From the showman I learnt nothing about the Elephant Man, except that he was English, that his name was John Merrick and that he was twenty-one years of age.

As noted, his actual name was Joseph Carey Merrick—not John. Every fictional representation of him has repeated this mistake. He has, largely, been consigned to the public consciousness as "John Merrick."

Note: I have not yet completed this small piece, but will update this post when I do. I have cut it here as it is already very long.

My original novel, Joseph (Zem Books, 2004), as part of a collection of my first novels from long ago.

Read my book: Theater of the Worm: Essays on Poe, Lovecraft, Bierce, and the Machinery of Dread by Tom Baker

Author's website

YouTube

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Comments (1)

Thank you for writing this Tom. I first heard off Joseph when David Bowie assumed the role of “John” for three months on Broadway. I have long been a Bowie fan. Shortly after I discovered the David Lynch film and of course I had to watch it - I was already a big fan of John Hurt from the film Midnight Express. I was drawn to The Elephant Man for several reasons. Thank you for bringing attention to Joseph - lengthy as it is it’s a good read.