The Man with the Bottomless Stomach: Tarrare, the 18th-century Frenchman who could eat cats, stones, and silverware.

The Gastric Abyss: Inside the 18th-century medical horror of the man who could swallow the world.

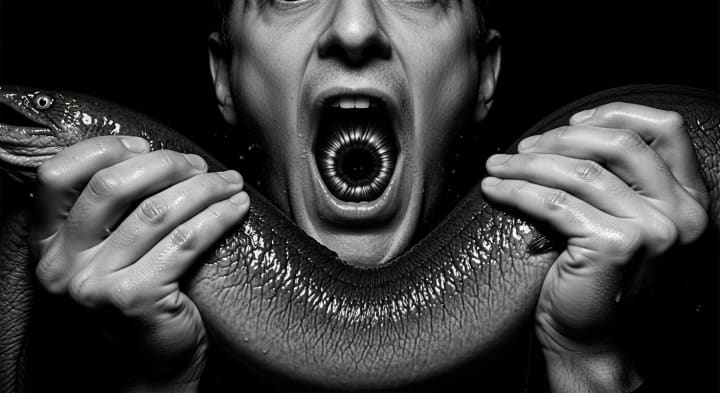

The wet, rhythmic sound of a cat’s skull cracking between a man’s molars is something the French military surgeons didn't quite know how to record in their ledgers. It was 1792. The air in the mobile hospital unit smelled of gangrene, scorched gunpowder, and the visceral, overwhelming stench of the man himself—a vapor so foul it was said to be visible, a shimmering miasma of rot that rose from his skin in waves. Tarrare didn't look like a monster. He was thin. He was pale. His cheeks were a deranged expanse of loose, folded skin that hung like curtains around a mouth that could open wide enough to swallow a basket of apples whole. He picked up a live eel, bit through its spine, and slid the thrashing length of it down his throat as if it were a noodle.

He was always, always hungry.

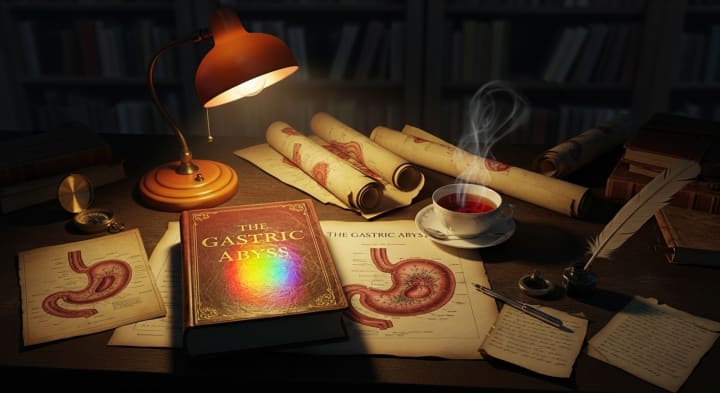

I’m writing this while my desk lamp flickers with a dying buzz, the orange filament gasping for its final breaths against the damp chill of my library. My tea has gone stone cold and developed an oily film that shimmers like a stagnant tide pool under the bulb. If I’m being honest, the sheer, unsettling logistics of Tarrare’s biology make my own stomach feel tight tonight. I’ve spent the better part of forty-eight hours buried in Dr. Hemmings’ 1924 report—a dusty, foxed monograph titled The Gastric Abyss: A Study in Hyperphagia, found in a box of "unclassified physiological horrors" in the basement of a London archive.

Hemmings was a man who saw the ghosts of the Enlightenment with a clarity that eventually broke him. He knew that Tarrare wasn't just a glutton. He was a biological sinkhole.

________________________________________

The Heresy of the Stretching Hide

Tarrare was born near Lyon around 1772. By the time he was a teenager, he could eat a quarter of a bull in a single day. His parents, terrified and impoverished, eventually turned him out onto the streets. He became a traveling showman. A freak. People would throw him stones, corks, and entire bushels of apples just to see them disappear into that unhinged maw.

When he was full, his stomach would swell like a massive, tight balloon. But when he was empty? That was the part that kept Hemmings awake at night. The skin of his abdomen would sag so drastically that he could wrap the folds of his own belly around his waist like a belt.

I had to read three different 18th-century medical journals to verify the "internal geography" of this man, and the details are purely alarming. When Tarrare opened his mouth, doctors could look straight down into his esophagus—a black, pulsing void that never seemed to register a signal of "enough." There was no satiety. There was only the hunt.

Dr. Percy and Dr. Didier, the military surgeons who eventually took him in, attempted a series of experiments that would be considered bizarre by any modern standard. They gave him a meal meant for fifteen German laborers. He ate the whole thing—two large meat pies, plates of grease, and gallons of milk—before falling into a deep, stinking lethargy. He didn't gain weight. He didn't grow strong. He remained a gaunt, shivering stick of a man, a parasite for his own organs.

________________________________________

The Alchemy of the Silver Messenger

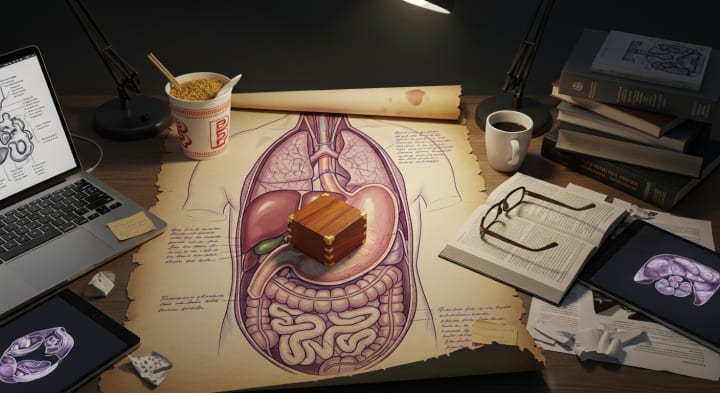

General Alexandre de Beauharnais thought he could use this deformity for the glory of France. He turned Tarrare into a spy. The plan was simple, if macabre: Tarrare would swallow a wooden box containing a secret message, travel across enemy lines to Prussia, and then "deliver" the box once it had passed through his system.

It was the ultimate secure transmission. No guard would think to look inside a man’s bowels for a military cipher.

The mission was a disaster. Tarrare was caught almost immediately. He didn't look like a soldier; he looked like a man having a mental collapse. The Prussians beat him, chained him to a latrine, and waited for the "delivery." When the box finally appeared, it contained nothing but a fake note—a test to see if Tarrare was reliable. The Prussians were so disgusted they nearly hung him. They eventually threw him back across the French border, broken and even hungrier than before.

I spent an hour yesterday staring at a diagram of the human esophagus in Hemmings' monograph. He had doodled a small, wooden box in the center of the stomach. He wrote:

"The soul is usually located in the heart or the head. In Tarrare, the soul was a wandering thing, trapped in the peristalsis of the gut."

If I’m being honest, the idea of a man whose entire existence is defined by the transit of a box through his intestines is the most lonely thing I’ve ever heard. He was a biological machine used for a purpose he barely understood.

________________________________________

The Pathology of the Forbidden Meat

The end of Tarrare’s story is where the darkness truly settles in. He returned to the hospital, begging Dr. Percy to cure his hunger. They tried everything. Laudanum. Wine vinegar. Tobacco pills. Nothing worked. Tarrare’s appetite grew more visceral.

He was caught sneaking into the apothecary to eat the poultices. He was found in the morgue, attempting to feed on the bodies of the dead. He was a wolf in the shape of a man. The orderlies began to lock the doors when they heard his soft, shuffling footsteps in the hall.

The final straw came when a fourteen-month-old child disappeared from one of the hospital wards. The doctors didn't have proof. They didn't find a bone or a scrap of cloth. But they looked at Tarrare—his mouth stained, his belly swollen, his eyes wide and alarming—and they knew. They chased him out of the hospital with bayonets. He fled into the Parisian night, a shadow fueled by a hunger that had finally crossed the last line of human decency.

He disappeared for four years. Some said he lived in the sewers. Others claimed he was seen eating carrion in the fields outside the city.

He resurfaced in Versailles in 1798, dying of tuberculosis. When he finally passed, the autopsy was a nightmare. The surgeons found that his stomach was so large it covered his entire abdominal cavity. It was covered in ulcers. His gallbladder was massive. The smell was so potent that the doctors had to cut the examination short. They couldn't breathe in the presence of his remains.

________________________________________

The Geometry of the Void

What was he?

Modern science might point to an extreme case of hyperthyroidism or a damaged amygdala. Perhaps a rare form of polyphagia caused by a tumor on the hypothalamus. But those words feel too clinical. They don't capture the bizarre tragedy of a man who was nothing but a mouth.

I sat in the library yesterday, touching a piece of 18th-century parchment that felt strangely thin. I thought about the skin of his cheeks. I thought about the eel. We like to think of our bodies as vessels for our "selves," but Tarrare was a vessel for a vacuum. He was a reminder that we are all just a few biological glitches away from becoming a mouth that never closes.

The lamp on my desk just gave a final, sharp pop, leaving me in the heavy, grey silence of the library. I can hear the floorboards creaking in the hallway—the house settling, or so I tell myself. But my mind keeps returning to the morgue in 1792. The image of a man crouching over a cold slab, his jaw unhinging to take in the world.

The tea is cold. The room is dark. And somewhere, in the back of the archives, Dr. Hemmings’ report is waiting for someone else to realize that hunger is the only thing that never truly dies.

We are all eating. We are all consuming. We just have the decency to stop when the plate is empty.

Tarrare never found the end of the plate. He just found the end of himself.

About the Creator

The Chaos Cabinet

A collection of fragments—stories, essays, and ideas stitched together like constellations. A little of everything, for the curious mind.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.