The Story of CineMouse

From Facebook Fans to Film Academy

From Facebook Fans to Film Academy: The Story of CineMouse

In 2015 in Bulgaria, an era when cultural institutions struggle to gather audiences while audiences effortlessly gather online, a curious reversal occurred in Bulgaria: a Facebook group became a film academy. What began as daily conversations about cinema evolved into a real ceremony, a real community and finally real awards. The project was called CineMouse, and behind it stood professor Peter Ayolov from Sofia University — lecturer in Media Scriptwriting and author of the book The Media Scenario (2026).

The story did not begin in a hall, a festival office or a ministry of culture. It began in a comment section.

The Group That Became a Public

As a film studies student at New Bulgarian University in Sofia, Peter Ayolov created the Facebook group “Recommend a Movie” as a space where viewers could exchange arguments rather than ratings. He placed at its centre the guiding slogan: “Watching movies will not make you wiser, making movies will not make you better, but talking about movies will make you wiser and better.” The sentence turned the group from a simple recommendation page into a living film seminar open to everyone.

The idea was simple: people suggest films to each other and discuss them seriously. No rankings, no algorithms, no influencers — only arguments.

Yet precisely this simplicity produced something rare in contemporary media: sustained conversation.

Members debated art cinema and blockbusters in the same thread. One day Andrei Tarkovsky, the next Christopher Nolan. Pasolini next to Pixar. Instead of separating taste communities, the group merged them. Students, engineers, doctors, programmers, teenagers and retirees entered a shared interpretive space.

The principle could be summarised by a paraphrase often repeated inside the community: watching films does not make you wiser, making films does not make you better — talking about films does both.

Unlike typical online groups built around agreement, this one was built around disagreement with respect. The group gradually became the largest Bulgarian online film community. People logged in every morning with coffee and every night with wine to continue conversations that sometimes lasted weeks. Members from different countries participated, but Bulgarian cinema remained a central passion.

Something important happened there: the audience became critics, and critics became a collective intelligence.

From Online Debate to Real Ceremony

At some point the endless arguments produced an inevitable question: if everyone debates winners anyway, why not actually vote?

The idea for CineMouse appeared spontaneously after yet another heated discussion. Instead of complaining about awards, the community decided to create its own.

No sponsors.

No industry jury.

No institutional backing.

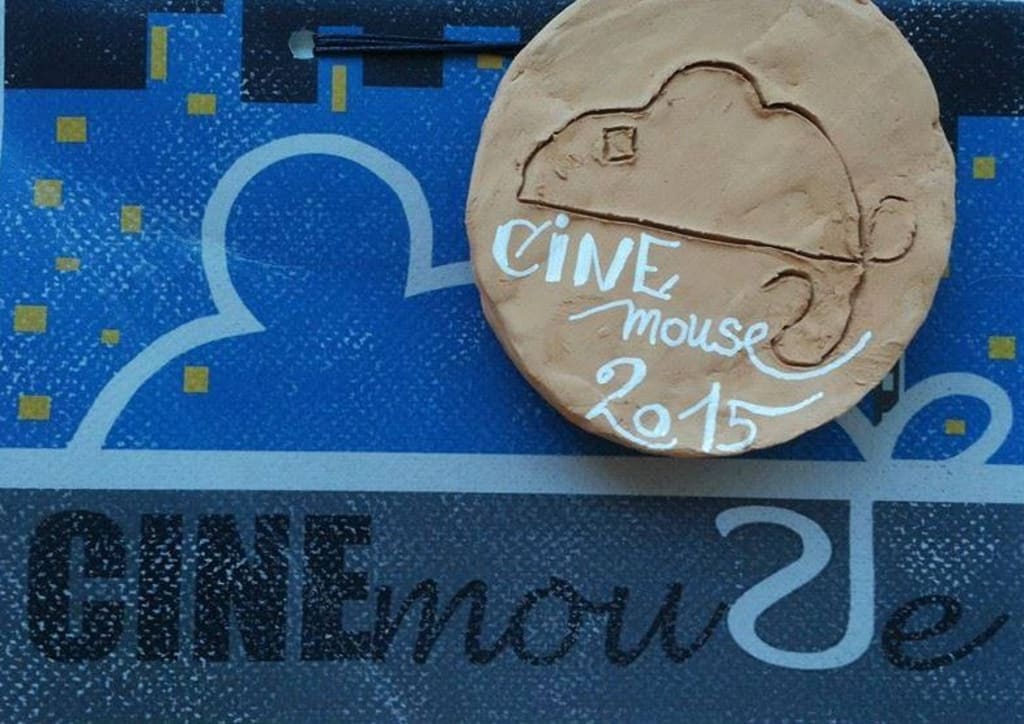

Everything was done by volunteers from the group — counting votes, designing graphics, editing videos, organising logistics and broadcasting live. Even the statuettes were handmade clay discs with a painted mouse, produced in Norway by students at an applied arts school connected to a Bulgarian artist.

The name combined three elements: cinema, computer mouse and home viewing culture — acknowledging how contemporary cinephilia exists between art and download, theatre and laptop.

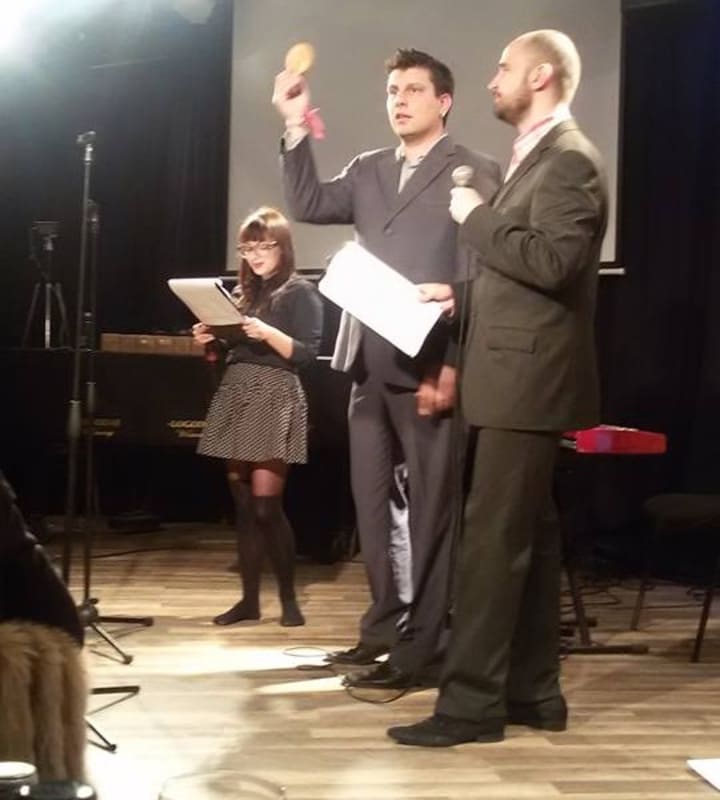

On 3 March the experiment left the internet and entered reality. Hall 5 of the National Palace of Culture in Sofia filled before the ceremony began. Many attendees met for the first time after years of nightly discussions online. The audience already knew each other’s opinions better than faces.

A virtual public became a physical one.

The First CineMouse Winners

More than nine thousand film enthusiasts participated in the voting. The results revealed something unusual: the collective taste balanced commercial cinema and arthouse works.

Best Film went to Birdman, competing with Boyhood and Interstellar.

Best Director went to Alejandro González Iñárritu.

Best Original Screenplay went to Richard Linklater for Boyhood.

Best Adapted Screenplay went to Terence Winter for The Wolf of Wall Street.

Best Cinematography went to Emmanuel Lubezki.

Acting awards honoured Matthew McConaughey and Cate Blanchett, while Jared Leto and Patricia Arquette received supporting role prizes.

Hans Zimmer won for music in Interstellar, and The Grand Budapest Hotel dominated design and editing categories.

The most meaningful result for the community, however, concerned Bulgarian cinema. The film Alienation won Best Bulgarian Film, competing with The Sinking of Sozopol and Victoria. The selection showed that the audience valued local cinema not from obligation but from genuine engagement — many members had democratic familiarity with both world classics and contemporary national productions.

Interestingly, several nominations later matched those of the Academy Awards, despite CineMouse announcing earlier.

But the organisers emphasised the difference: the process here was radically democratic. Every member emailed personal nominations, and volunteers manually counted votes. Exhausting, but transparent.

Why CineMouse Matters

CineMouse was not merely an alternative award. It was an experiment in media sociology.

Professor Ayolov’s academic work in media scriptwriting focuses on narrative communities — how audiences do not only consume stories but collectively construct meaning around them. The group unintentionally became a practical laboratory for this theory.

Traditional awards represent industries judging themselves. CineMouse represented interpretation judging art.

No marketing campaigns influenced voting.

No distribution budgets determined visibility.

Only discussion produced recognition.

Participants reported that friendships, relationships and even romances emerged from shared taste. The ceremony therefore celebrated not only films but also a rare form of digital sociality — disagreement without hostility, expertise without hierarchy.

In an age of algorithmic recommendation, the group functioned as a human recommendation engine. The awards formalised what already existed: a deliberative cultural public.

A Different Kind of Academy

Unlike prestigious ceremonies dominated by glamour, CineMouse deliberately avoided gold statues and luxury symbolism. The clay mouse disk emphasised modesty and collective authorship. The award’s value came from attention, not prestige.

For many filmmakers the gesture was unexpectedly meaningful. Their work reached a concentrated audience that had actually watched and debated the films deeply. The awards therefore measured engagement rather than exposure.

The ceremony was streamed online for members unable to attend. Thousands watched simultaneously — a hybrid ritual combining digital gathering and physical event.

One participant later wrote that the evening proved friendship could exist in disagreement and creativity could arise from voluntary labour.

From Group to Cultural Institution

What began as a Facebook page became something close to a civic cultural institution. Without official mandate, the community performed functions traditionally associated with film academies: curation, criticism, canon formation and celebration.

The paradox is revealing. Social networks often fragment attention, yet here they produced concentration. Instead of replacing cultural spaces, the internet rebuilt one.

CineMouse demonstrated that audiences do not only want to consume culture — they want to participate in evaluating it. The ceremony was less about winners and more about shared judgement.

The Legacy

After the ceremony the handmade awards were sent to winners across Europe and the United States, carrying with them an unusual message: a national audience, self-organised online, had spoken.

For Bulgarian film culture the significance lay not in competition with official awards but in proving that cultural authority can emerge from discussion rather than institution.

For media theory the case illustrated something deeper: communities form not around content but around interpretation. A public is created when people argue seriously about meaning.

Professor Ayolov’s group unintentionally showed that the future of criticism may not belong to professional critics nor to algorithms but to organised audiences capable of sustained conversation.

CineMouse therefore was not only a film award. It was a demonstration that culture still depends on dialogue — and that sometimes a comment section, if taken seriously enough, can become a cultural academy.

RECOMMEND A MOVIE! — a group for film recommendations and discussions!

MOTTO:

“Watching movies will not make you wiser. Making movies will not make you better. Talking about movies will make you wiser and better!”

**GROUP RULES:**

1. The admins have full authority!

2. Complaints are not allowed.

3. The group must not be taken seriously.

The group is dedicated to the memory of Plamen Bakardzhiev — cinematographer, Alexander Etimov — film editor, and Milen Pushnikov — actor.

**ADVICE: HOW TO TALK ABOUT MOVIES WE HAVE FORGOTTEN? (after Pierre Bayard)**

The films we talk about are often only “screen-films” and have little to do with the “real films”. Most statements we make about films actually concern other comments about films. Thus films become merely a pretext for an endless discussion with all the people who have spoken and will speak about them. The film hides behind language in this closed fractal centrifuge of infinite commentary.

Already while watching, we begin internally speaking about the films. Afterwards we deal with these statements and opinions, pushing far away the real films, which become forever hypothetical.

The art of talking about films occurs when a reasonable distance from films as individual works is maintained and a “general view” of cinema as a living system is sought.

Culture is above all a matter of orientation. The most important knowledge is knowing where you are at the moment.

About the Creator

Peter Ayolov

Peter Ayolov’s key contribution to media theory is the development of the "Propaganda 2.0" or the "manufacture of dissent" model, which he details in his 2024 book, The Economic Policy of Online Media: Manufacture of Dissent.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.