'Unknown life form' is the term scientists use to describe a 26-foot-tall fossil from 400 million years ago.

Devonian's largest organism

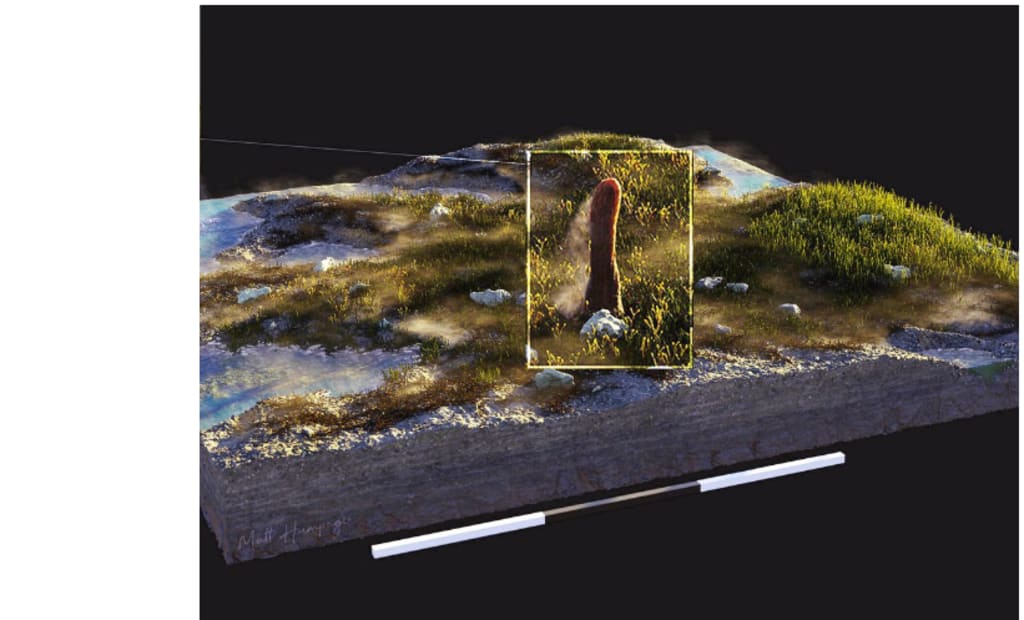

Prototaxites is a peculiar fossil that has baffled scientists for more than 165 years. It was odd even in appearance. It looked like a massive, leafless tree and reached a height of 26 feet.

About 400 million years ago, during the late Silurian period, these odd lifeforms first appeared. They lacked branches and bore little resemblance to current trees, and were found among early ferns and horsetails.

John William Dawson, a Canadian geologist, believed these fossils to be decaying tree trunks in 1859. Even as the confusion grew, he continued to refer to them as "first conifers."

As new instruments have been applied by modern science, the enigma has only gotten bigger, but the answers have remained elusive.

Prototaxites: Were they fungi?

The theory that Prototaxites was a fungus gained traction for many years. Based on anatomical characteristics such as the existence of tubular structures, palaeontologist Francis Hueber hypothesised in 2001 that it was a huge terrestrial fungus.

Later, in 2017, scientists discovered what they thought were fruiting bodies in the fossil, connecting it to the contemporary fungus genus Ascomycota. The issue was that it had never been demonstrated that these purported reproductive organs connected to the vegetative body. That was concerning.

Might these pieces have come from a completely other organism? Prototaxites' fungal identification was left up to speculation in the absence of concrete proof. The fungus theory remained in place despite continuous discussion. That is, until a group headed by University of Edinburgh scholars looked more closely.

One of the best fossil beds from the early Devonian period, the Rhynie chert in Scotland, contains the species Prototaxites taiti, which they re-examined. Their discoveries challenge all of our preconceived notions.

Devonian's largest organism

The group concentrated on a fossil known as NSC.36 that was remarkably well-preserved. This specimen displayed a cross-section of P. taiti, revealing black, round markings called medullary spots dispersed throughout the body.

Though fragmentary, the rock sample used for analysis was approximately cylindrical, measuring 5.6 cm (2.2 inches) in width and nearly 7 cm (2.8 inches) in length. This implies that the original organism was considerably bigger and most likely a dominant presence in its surroundings.

The scientists found three different kinds of tubes extending longitudinally through the fossil at the microscopic level. Type 2 tubes had smooth double walls and no internal cross-walls, whereas Type 1 tubes were branching, thin, and septate.

The thickest tubes were variety 3, which had ring-like thickenings that were unrelated to any known fungus variety. Within the fossil, these structures seemed to be knitted together to form a thick, interconnected network.

It's interesting to note that these anatomical features shared some characteristics with mushrooms, but not enough to be a match. There were obvious concerns because the third tube type, with its annular thickenings, is not found in any known fungus group.

Unusual medullary spots without equal

The researchers conducted a detailed analysis of the medullary spots using 3D imaging and confocal laser scanning microscopy.

All three tube types were present in these areas, along with much finer ones—some as small as 1 micron in diameter. Inside, the branching patterns were intricate and lacked the distinct order found in fungal systems today.

Branching in contemporary fungus is hierarchical; generative hyphae produce other types in a predictable manner. However, P. taiti's branching lacked a distinct direction or order. A chaotic mesh of tubes connecting in all directions. The researchers pointed out that "no structures similar to medullary spots exist in extant fungi."

Additionally, they denied that these patches resembled ascomycetes' fruiting structures. There is no organic link between these spots and any purported reproductive structures, despite the fact that some scientists originally believed the marks suggested spore formation.

Fungal or plant characteristics were absent in prototaxites.

The scientists next used FTIR spectroscopy to examine the molecular composition of the relic. They contrasted P. taiti with bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals that were found in the same deposit. Because all of these fossils had gone through the same fossilisation process, a trustworthy side-by-side comparison was possible.

The outcomes were remarkable. The vital substances chitin and chitosan, which are present in fungal cell walls, were completely absent from the fossil. Although it was found in the surrounding substratum, P. taiti did not have perylene, a chemical indicator of ascomycete fungi.

Rather, aromatic and phenolic molecules that resembled fossilised lignin were found in P. taiti's cells. Although terrestrial plants have lignin, this form was chemically different. It was something really different—like lignin, but not like a plant.

Its isolation is confirmed by machine learning.

The team employed machine learning techniques to test the molecular data further. By using their molecular fingerprints, these models were trained to differentiate between different creatures.

The outcomes were evident. With more than 90% accuracy, the models distinguished P. taiti from bacteria, fungi, animals, or plants.

The authors state that P. taiti is best regarded as a member of an as-yet-undiscovered, completely extinct group of eukaryotes because its morphology and molecular fingerprint are "clearly distinct from that of the fungi and other organisms preserved alongside it in the [Devonian deposit]."

Prototaxites is unique in that no other taxonomic group is known to share its combination of morphology, chemistry, and lifestyle. The only similarity is that it was a eukaryote, which means that it had complex cells with nuclei.

Not an animal, fungus, or plant

The investigators examined all potential affiliations. Is that an algae? No, P. taiti was chemically different and lacked the required photosynthetic structures.

Is it an early terrestrial plant? Once more, that was ruled out by the lack of vascular tissues and other characteristics of plants. What about lichen? Without a photobiont, it would be impossible. Oomycetes? The molecular makeup was different.

Animals were excluded as well. P. taiti obviously had tube-like cell wall features, which are not found in metazoans. The team's classification table ultimately displayed the same outcome for each group: rejection.

Prototaxites: The lost experiment of evolution

It is possible that prototaxites are the last known members of their kind. From subterranean networks, it created enormous vertical constructions.

It most likely, like contemporary saprotrophs, took up nutrients from decomposing materials. But it wasn't an animal, a plant, or a fungus.

The authors came to the conclusion that Prototaxites are unique because they could not be linked to any existing lineage based on their examination.

And we might only ever know that. As a member of a long-extinct branch of life, Prototaxites only remains as a fossil and has no living relatives or modern descendants.

Unlike the modern world, the ancient world was teeming with life. One of its most audacious experiments—and possibly one of its most intriguing failures—was prototaxites.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.