Swill milk's history starts in the early 1800s, especially in quickly expanding cities like New York. The demand for fresh milk increased in tandem with the growth of metropolitan populations. However, in the boundaries of a busy city, traditional dairy farming practices—which entailed grazing cows in broad pastures—became more and more impracticable. Due to this logistical difficulty and the demand for inexpensive milk, dishonest dairymen were able to take advantage of distillery waste, a resource that was easily accessible and appeared to be free.

Large amounts of whiskey and other spirits were manufactured by distilleries, which also created a massive byproduct called spent grain, sometimes referred to as "swill" or "slops." Some ingenious, if morally reprehensible, people realized that this wet, fermenting mash might be utilized as cow feed, even though it was an annoyance to dispose of. As a result, "distillery dairies" appeared, frequently next to or even inside the distilleries.

These were hardly the pastoral imagination's picture-perfect farms. Rather, they were claustrophobic, dirty, cruel institutions. In cramped stables, cows were chained and frequently knee-deep in their own feces. The air was heavy with the smell of fermenting grain and animal feces, there was little sunlight, and ventilation was inadequate. These cows were only used to turn distillery swill into a beverage that could be marketed as milk, regardless of the quality of the milk or the pain the animals endured.

The Unpalatable Ingredients: What Made Swill Milk So Dangerous

As might be expected, distillery swill was the main component of the diet of swill milk cows. The cows in these distilleries were fed this acidic, nutrient-deficient waste almost exclusively, even though spent grain can occasionally be included in animal feed. This diet, combined with the deplorable living conditions, had a profoundly detrimental effect on the cows' health and, consequently, the quality of their milk.

The Cows' Predicament: The cows' continual ingestion of swill caused a number of crippling health problems. They experienced liver issues, persistent indigestion, and general deterioration. They suffered from dull, matted coats, brittle bones, and various skin conditions, including scrofula, a type of tuberculosis that affects the lymph nodes. Despite the fact that their udders were frequently swollen and infected, they were constantly milked, sometimes even after passing out from illness or exhaustion. Their anguish was reflected directly in the milk they produced.

The Milk's Composition: The composition of the milk was a far cry from the healthy product that swill milk was supposed to be. It usually lacked the inherent richness of healthy cow's milk and was thin and bluish. Its poor nutritional content was a major worry, particularly for young children and babies who depended on milk as their main food supply. However, the issues were not limited to malnutrition.

The milk was highly contaminated with microorganisms as a result of the unhygienic surroundings. It was inevitable that the milk would contain feces, pus from infected udders, and other dirt. In order to cover up the milk's sour taste and pale look, dishonest dealers used a terrifying variety of adulterants. These included:

Chalk or plaster of Paris: Added to whiten the milk and give it a thicker consistency.

Starch: Used as a thickening agent.

Water: The most common adulterant, used to increase volume and dilute the already poor-quality milk.

Molasses or burnt sugar: To add a deceptive sweetness and color.

Calf's brains or other animal parts: Allegedly used by some to provide a richer texture, though this claim is particularly abhorrent and less widely documented than other adulterants.

Putrid eggs and stale beer: Other anecdotal, but equally disgusting, additions reported to improve color or taste

Even if the milk had a low bacterial count at first (which was uncommon), it would soon deteriorate due to the lack of refrigeration, becoming dangerously rancid. By adding poisonous compounds to an already dangerous product, the adulterants increased the health hazards.

A Scourge on Public Health: The Devastating Impact of Swill Milk

Consuming swill milk had disastrous results, especially for the most defenseless members of society—infants and young children. Many low-income families were compelled to rely on this inexpensive, contaminated product because they lacked access to safe, wholesome substitutes.

Infant death: The rising infant death rate in urban areas was the most catastrophic effect of swill milk. Infants who were given this tainted milk frequently experienced severe gastrointestinal disorders, such as vomiting, diarrhea, and symptoms similar to cholera. The assault of bacteria and toxins was too strong for their immature immune systems to handle. The underlying cause of death was commonly swill milk, although death certificates typically cited "marasmus" (severe malnutrition) or "summer complaint" (a euphemism for diarrheal disorders common in warm weather) as the cause of death. Swill milk is thought to be the cause of thousands of baby deaths per year in some urban areas.

Disease and Debilitation: Swill milk contributed to chronic illness and widespread disease in the general population, in addition to infant mortality. Its consumption was frequently associated with scarlet fever, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, and other types of food poisoning. People's immune systems were also compromised by inadequate nourishment, leaving them more vulnerable to illnesses. The health of entire communities was compromised, creating a vicious cycle of poverty, illness, and despair.

Public Outcry and Early Awareness: During the early stages of germ theory's scientific development, wise observers—such as doctors and social reformers—started to see the connection between the terrible conditions of distillery dairy and the widespread illness and fatalities. Dr. R.M. Hartley of the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor was one of the early reformers who relentlessly opposed the practice by exposing the atrocities of swill milk through lectures and articles. They emphasized the terrible effects on human health, the filthy production practices, and the cruel treatment of animals.

But change was vehemently opposed by established interests, such as wealthy distillery owners and dishonest politicians. They argued against government intervention, minimized the health risks, and even filed libel suits against anyone who dared to reveal their practices. The urban poor, who had few options, continued to be a captive market due to the strong economic incentive to manufacture inexpensive milk.

The Fight for Pure Milk: The Discontinuation of Swill Milk

Swill milk's eventual demise was the result of decades of unrelenting activism, advances in science, and a growing public demand for safer food—it wasn't an abrupt event. Its discontinuation was caused by several important factors:

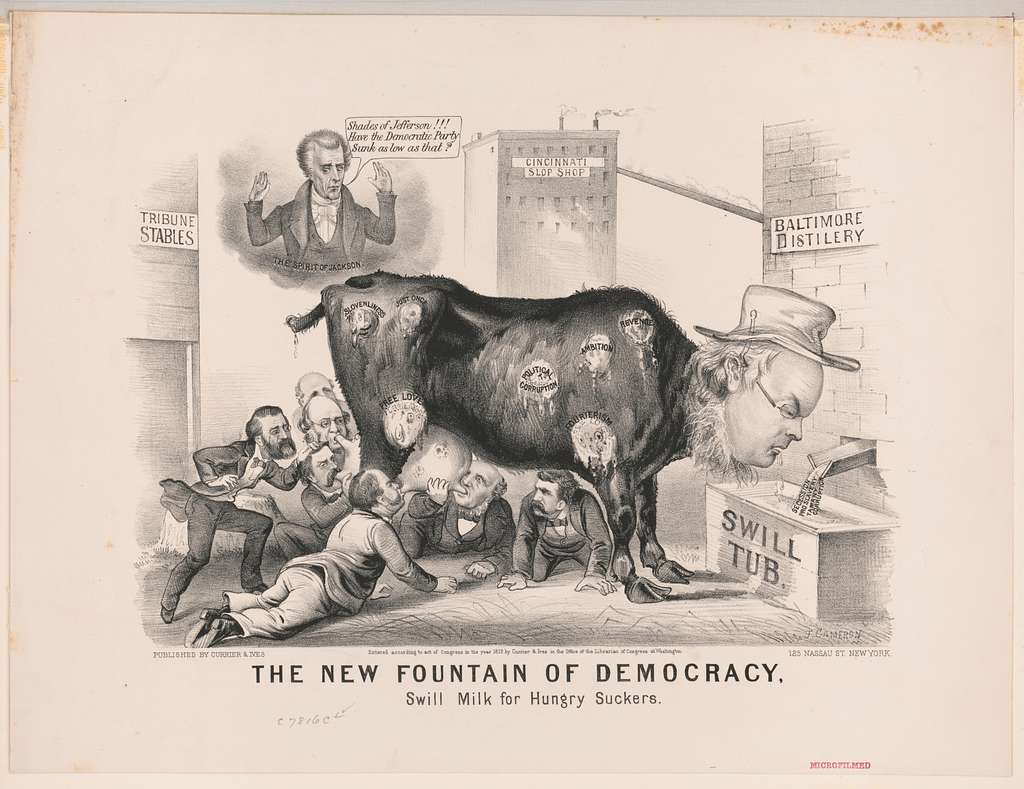

Investigative Journalism: Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper's investigative journalism was one of the most important turning points in the campaign against swill milk. The filth of the distillery dairies, the malnourished cows, and the accompanying tainted milk were vividly portrayed in a series of articles published in 1858 with startling illustrations. These exposés sparked public indignation and cemented the perception of swill milk as a public health threat, especially the widely shared image of a "swill milk" cow. Because of how effective the illustrations were, they are still cited as early muckraking journalism examples today.

Scientific Advancements: The scientific foundation for comprehending how milk became contaminated and how pasteurization could make it safe was established by the developing field of microbiology, which was led by individuals such as Louis Pasteur. Although pasteurization was not immediately widely accepted, reformers' arguments were reinforced by scientific knowledge of bacteria and how diseases spread. Additionally, techniques for testing milk for adulteration and purity advanced in sophistication.

Public Health Movement: A strong public health movement emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Reformers, social workers, and medical professionals began to advocate for government regulation of food production, improved sanitation, and better public health infrastructure. One of the main pillars of this larger campaign was the struggle for unadulterated milk. The promotion of cleaner milk production and distribution was greatly aided by groups such as the New York Milk Committee, which was founded in 1906.

Legislative Action and Regulation: Local and state governments progressively started to pass laws to regulate the dairy business in response to growing public demand and scientific data. Laws were passed prohibiting the feeding of distillery swill to cows, mandating sanitary conditions in dairies, and establishing standards for milk purity. Although enforcement was frequently difficult in the beginning, inspectors were assigned to police these regulations. Although they had a wider reach, the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 further highlighted the growing importance of the federal government in guaranteeing food safety.

Technological Advancements: The need for urban distillery dairies was lessened as refrigeration technology allowed milk to be transported over greater distances without spoiling. Milk could now be obtained from remote farms with healthier cows and improved hygienic standards thanks to the development of refrigerated railcars. Urban "cow barns" became less competitive as a result of this fundamental shift in the economics of milk production.

Changing Consumer Demands: As people became more aware of the risks associated with swill milk, they started to demand "pure milk" from reliable sources, especially those who could afford it. As a result, there was a need for dairies that followed stricter guidelines for animal welfare and cleanliness. A premium product was created by the idea of "certified milk," which was produced in hygienic circumstances and subjected to frequent testing.

The Legacy of Swill Milk

Swill milk was virtually extinct in major American cities by the early 1900s. Its demise was a landmark in the history of food safety and a major win for public health. However, swill milk's legacy goes beyond its extinction.

It serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of:

Ethical food production: The swill milk era highlighted the dangers of prioritizing profit over public health and animal welfare.

Government regulation: It demonstrated the necessity of strong regulatory frameworks to ensure the safety and quality of food products.

Investigative journalism: The role of the press in exposing corporate malfeasance and raising public awareness was crucial.

Public health advocacy: The tireless efforts of reformers and activists were instrumental in bringing about change.

Consumer awareness: An informed and engaged public is essential for demanding safe and healthy food.

Although the history of swill milk is a somber one, it also serves as a reminder of the strength of group effort and the persistent human yearning for a more equitable and healthy society. It established the foundation for contemporary food safety regulations and now emphasizes how vital attention to detail is to preserving our food supply.

About the Creator

Richard Weber

So many strange things pop into my head. This is where I share a lot of this information. Call it a curse or a blessing. I call it an escape from reality. Come and take a peek into my brain.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.