The earliest fossilised vomit in the world with intact remains is found by scientists.

A moment that was locked in

The oldest known vomit from a terrestrial mammal is a lump of fossilised vomit that is around 290 million years old. An early land food chain can be redrawn thanks to 41 bone fragments that freeze a single meal from long before dinosaurs.

Tiny bones were grouped together rather than dispersed throughout the walnut-sized mass that was buried in the Bromacker sandstone in central Germany. Palaeontologist Arnaud Rebillard of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin (MfN) interpreted the bulge on the slab as a hint.

A thorough analysis mapping the lump's bones and claiming they originated from regurgitated stomach contents was later published by Rebillard and associates. Because of that conclusion, the cluster became a direct record of eating, which is typically concealed by fractured skeletons in fossils.

How puke turns into fossils

Fossilised vomit, or hardened stomach remnants released from the mouth before digestion is complete, is referred to by researchers as regurgitalite. Sharp bones may become glued into a compact clump during the heave by digestive secretions and sticky mucus.

Since the light, scavengers, and rushing water can tear loose parts apart, fast burial then closes the packet. Since those odds are low on land, every preserved regurgitalite can provide insight into behaviour that skeletons alone are unable to capture.

Digitally sorting bones

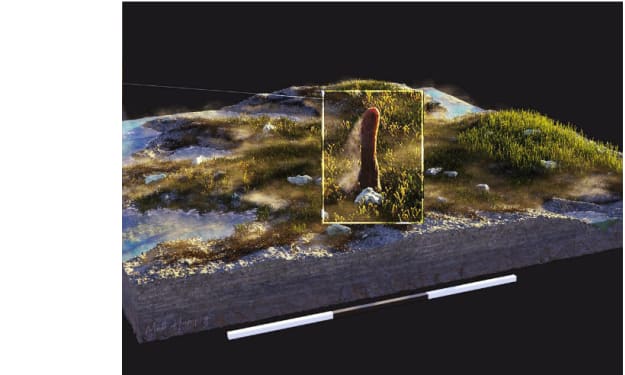

The scientists employed micro-CT scanning, a high-resolution X-ray scan for microscopic fossils, to prevent splitting the specimen open. Software divided the denser bits into a clear digital representation since X-rays went through bone differently than they did sandstone.

Following the separation, scientists turned each bone over and compared its shape to better-preserved Bromacker skeletons stored in MfN cabinets. Because some bones were less than an inch and more prone to crumbling, it was important that nothing left the rock while scanning.

Three species of prey

The vomit comprised the remnants of three creatures, not just one unfortunate victim, according to matches to the site's fossil collection. Thuringothyris mahlendorffae, which is about 3.5 inches long, fit one pair, and Eudibamus cursoris, which is about 4 inches long, fit another.

The third prey animal was an unnamed Diadectes-related diadectid that was around two feet long. The bones were unable to identify the predator at this time since no teeth marks or pieces of the eater's skull survived.

hints derived from chemistry

By following phosphorus, which frequently concentrates in coprolite, fossilised faeces that have solidified into rock, chemistry was able to distinguish between vomit and excrement. Unlike usual faecal fossils, the sediment adjacent to the bones in the vomit cluster contained minimal phosphate.

Although the surrounding cement appeared more like floodplain muck than digested garbage, bones still contained their own phosphorous. The animal's early expulsion of a compact pellet before the gut had had time to properly process it was supported by that chemical signature.

An untidy eater

Combining several prey in a single bite indicated opportunistic feeding. Before acids weakened the bones, a predator could seize a little reptile, catch another nearby, and consume both.

The mass's aligned long bones indicated that it left the body in one piece rather than as separate pieces. Since most fossils in early land rocks depict corpses after death rather than meals, there is little direct evidence of predator-prey relationships.

Following the predator

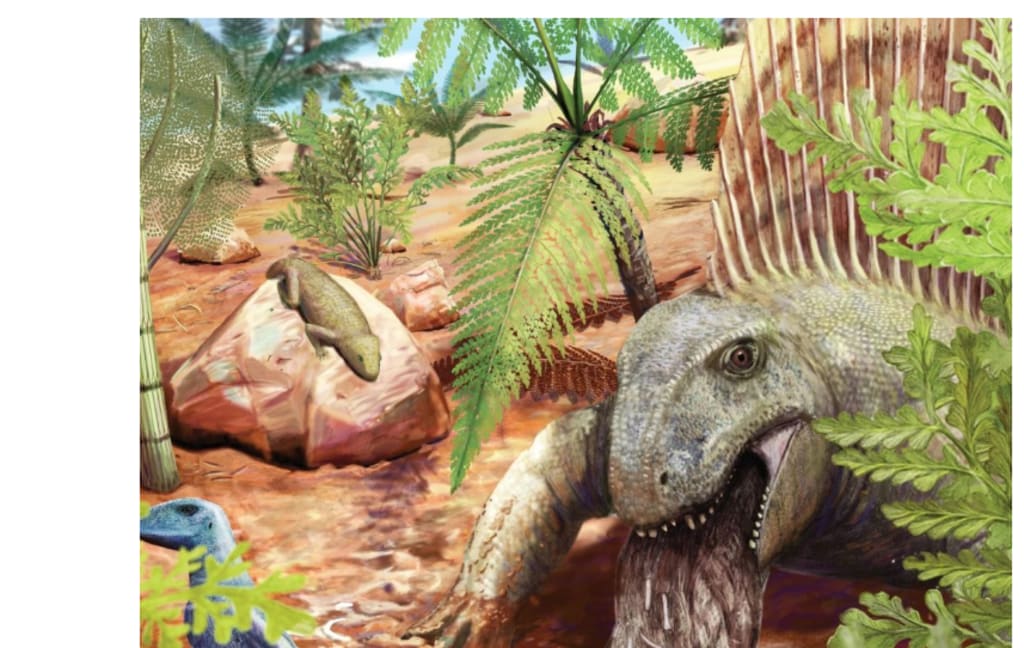

The magnitude of the bone cluster and the creatures residing there were only matched by two huge predators from Bromacker. Tambacarnifex unguifalcatus and Dimetrodon teutonis were both members of the synapsid branch of vertebrates, which gave rise to mammals.

The producer was considered a best-fit suspect by the authors because neither predator left a tooth in the lump. Because it limits how scientists reconstruct the top of that food chain, limiting it to a short list is still important.

Why Bromacker is unique

Scientists can now correlate bodies to behaviour since Bromacker has produced full land skeletons and trackways, unlike many other fossil quarry. The distance that bones might drift was limited by the thin layers of mud and sandstone that were exposed by repeated excavations.

Thomas Martens originally collected bones from the quarry in 1974, and subsequent teams came back for years to increase the record. A single regurgitated lump can be compared to numerous known creatures, putting MfN on an uncommon footing as a result of that sustained effort.

A moment that was locked in

The Bromacker valley was formerly traversed by transient streams, with fir trees lining the banks where remains might be buried by flood muck. The clump did not require biting marks on a fossilised skeleton to document who ate whom because it only recorded one regurgitation.

Rebillard described the rarity of such direct records on land as "like a photograph of the past, taken at a specific moment." This predator already serves as an anchor for a true food web, but finding more regurgitalites would test if those predators hunted selectively.

Where this goes

The fossil vomit allowed scientists to see a predator-prey network that is hidden by bodies alone by connecting disparate bones into a single event. Future discoveries from Bromacker and related locations may provide insight into the feeding habits of early land predators and the frequency with which they coughed up food.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.